| |

The Luristan Project - Results from Cut Sword; Part 4

|

Discussion of the "Cut Sword" Findings

|

| The Findings |

|

Most everything of interest has already been stated in the three preceding

modules. For starters I will therefore give a description of how we envision the sword was made. I base this on our findings

and on some straight-forward logical deductions. Further down I will discuss how that ties in with what is known from the

literature. |

| |

|

|

Raw Material |

|

|

The raw material used for forging the swords must have been some bloom from an

800 BC or so (and thus relatively early) bloomery. Those blooms might have been compacted and thus purified to some extent

right after smelting but they still must have contained a lot of slag and possibly some other inclusions. Their carbon content

strongly varied (from ferrite / wrought iron to hypereutectoid steel) even so the bulk of the bloom was probably low in

carbon. |

|

|

The only raw material that is known to me from the time period in question (ca.

800 BC – 550 BC) are the Assyrian

"double pyramid bars" found in the palace in Dur Sharrukin (present-day Khorsabad),

the capital of Sargon II from 717- 705 BC.

Khorsabad is

close to Ninve and thus not all that far from Luristan. In fact, during its

largest expansion around 650 BC, the Assyrian empire may have contained parts of Luristan.

To quote myself: "Sargon II, who ruled the Assyrians from 722 BC – 705 BC, was in possession of a tremendous treasure

of iron that was stored in the palace of his capital Dur Sharrukin, present-day Khorsabad. One Victor Place, resuming excavations

started by Paul Botta in 1843, found 160 tons of iron just in storeroom 84. Most of

that iron was in the form of bipyramidal bars weighing 4 kg - 20 kg. Metallographic investigations by well-known Radomir

Pleiner showed that this iron was rather non-uniform stuff, a mixture of wrought iron, mild steel and hard steel steel,

with plenty of slag inclusions.". Fits the Luristan iron like a glove. Just a coincidence? |

|

|

If an average bloom weighs in at 10 kg, Sargon's treasure involved 16.000 smelts.

Considering that this was just the strategic reserve and that far more iron was most likely out there in the form of weapons

and tools, Sargon's Assyrians must have made and forged iron on an industrial base. This implies that plenty of experience

and highly skilled smiths were around then and certainly also before Sargon's II reign since this kind of industry does

not come into being over night. However, besides the Khorsabad treasure, we have no iron whatsoever from the Assyrians (or Babylonians).

In contrast, we have the 100 or so Luristan iron

swords (plus a few other iron objects) - but nothing whatsoever is known about smelting and working iron in Luristan.

|

| |

| |

|

Starting Material |

|

|

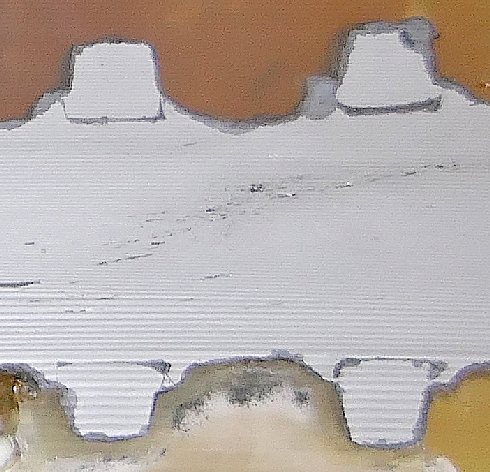

From the results we can state with certainty that the ancient smiths did not

start to forge a mask sword directly from the bloom. They rather prepared a range of intermediate semi-products as starting

material for making the various parts of the sword. It appears from our results that they first forged thin sheets. The

elongated slag inclusion always show a large length-to-width ratio, just what you would get if you forge a cube into a sheet

that is much longer than the cube and accordingly thinner. Double-pyramid bars by the way, are a good shape for drawing

out thin and long strips as evidenced in this picture

By cutting these single sheets to suitable dimensions followed by stacking them in a way that approaches the desired

final shape, fire-welding these layers then allows to produce billets that already assumes the basic shape of the various

parts needed. That is particularly attractive for the blade and the hilt; especially if only one piece was used.

Fire-welding

might have been done by forging the stack of pre-shaped sheets or, if the shape attempted was simple, by stretching and

folding, i.e. by faggoting.

Here we propose something new that you will not

find in the literature. Mind that we do not claim that this technique was used for all mask swords. Mind also that around

800 BC iron technology made a big step forward and that composing

blades by layering / faggoting was used by the old Celts as demonstrated by the "sword

from Singen" |

|

|

However - the ancient smiths were not too careful in doing this since the finished

stacks, as shown by all our pictures, contains very bad (many large slag inclusions) and very good iron pieces in a seemingly

arbitrary manner. Maybe they couldn't do better or - maybe once more - they didn't care since the mask swords were definitely

not designed for fighting but only for showing off.

Only the outside had to look

good, the inside quality didn't matter at all- in stark contrast to a fighting sword!.

The outside quality mattered for two reasons.:

- You wanted a blade that looked perfect, without visible flaws on the outside. This necessitated that the top and bottom

sheets of the blade / hilt stack was made from "good" iron.

- Wherever you wanted to put on the figures on the lower hilt and pommel plate or the rings by crimping,

you had to make sure that these parts consisted of soft iron, i.e. ferrite or mild steel. I strongly believe that it is

simply impossible to chisel off the crimps and bend them over the figures / rings if you encounter the brittle hypereutectoid

steel found in several places.

Indeed, as far as investigated, these parts of the blade / core did consist of relatively

good ferrite.

We are thus claiming that the ancient smiths knew that their material came with different hardness values (i.e. carbon

concentration) They could forge thin sheets and had a way of sorting the stuff. "Good" iron for the poutside,

the "bad" one for the inside. |

| | |

|

|

Basic Forging |

|

|

The artisans making the Luristan mask swords were experts at their trade. They

knew not only how to fire-weld but in particular how to make an object with a complex shape out of a (by now layered and

possibly pre-shaped) billet) of iron / steel. The next step involved forging the various pieces as closely as possible into

their final shapes. This included the rough shaping of the heads and animal figures but also of the pommel plate and the

"rings" around the hilt. Doing that would be a challenge to a modern smith today. It was important that the shape

after forging was as close as possible to the final shape because that made the tricky and laborious next step easier.

Forging itself did take place at rather high temperatures followed by relatively fast cooling (water quench?) as evidenced

by the Widmanstätten structures and other observations outlined in the preceding parts. That seems to be true for pretty

much all swords because all investigations made so far agree on this point. High temperature forging requires a hearth of

some sophistication and skilled helpers.

There is, however, also evidence for low-temperature forging and even cold

forging. Small wonder since the final steps of assembling the sword did need some high temperature but as little as possible.

The chisel work for crimping obviously had to be done at room temperature. Then there might have been some short medium

temperature annealing after all was done. |

| | |

|

|

Final Shaping of the Parts |

|

|

The various parts had to be worked into their final shape and that involved:

- Grinding and polishing the "simple" parts like the blade / hilt piece, the pommel plate, and the "wires"

for the rings. Sounds not too difficult but try to do that by hand without the benefit of standardized emery paper, all

kinds of files, and grinding wheels / power tools.

- Carving the figures. As pointed out in the main

text, that was the only way you could produce these enigmatic heads and "lions". How do you do this without

a range of good steel tools? Well, maybe they had steel tools? We don't know but I think it is quite likely. In any case,

they obviously did have some artists (not smiths) who could turn the raw pieces into a finely detailed sculptures.

|

|

Assembling the Parts |

|

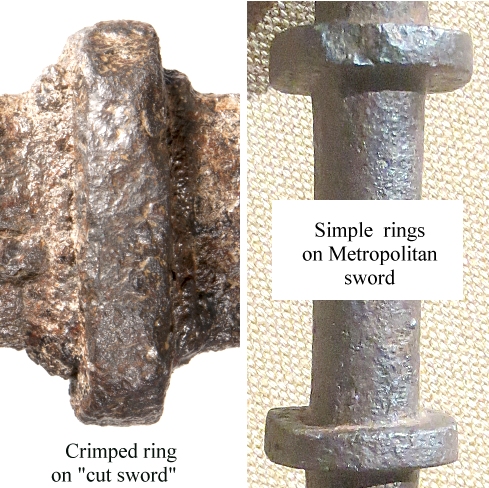

Attaching the Rings

If you

had made the core of the sword (hilt and blade) from one piece of material, I'm rather sure that in a first step the rings

were attached. Looking at Luristan iron swords you will find that some rings were just wound tightly around the grip, while

others were tightly wound etc. but also crimped into place. The following pictures show this |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

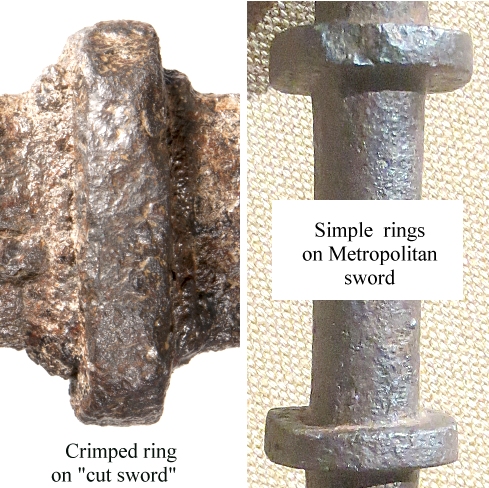

Left: One of the rings on the "cut" sword discussed here.

Right: The rings on the Luristan sword in the Metropolitan;

New York |

| Source: Left: Project; right: photographed in the Metropolitan Museum Feb. 2020 |

|

| |

|

|

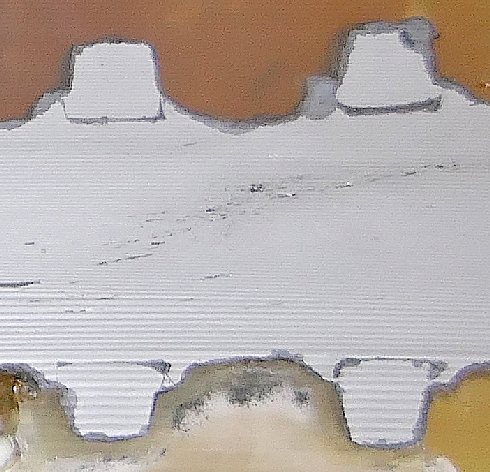

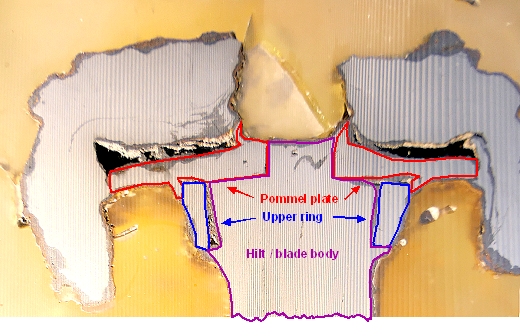

| Cut showing the crimping around the rings |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| Straight and crimped rings around two of my swords |

| Source: Photographed by me 2020 |

|

| |

| |

|

|

There is no way to bend a partially elastic wire / ring around the hilt at room

temperature in such a way that it snugs closely to the hilt at all places. You need to do that at a raised temperature,

in particular if he material consists of hard steel as found in the rings. . |

|

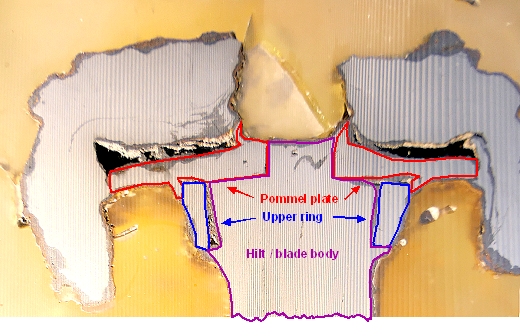

Attaching the pommel plate

The pommel plate is kind of riveted on, using the thin extension of the hilt that fits through a hole in the pommel plate.

A picture says more than thousand words: |

| |

|

| | |

|

| Pommel plate and upper ring attachment |

|

| |

| |

|

|

We guess that at this stage the head / animal figures are not yet attached tot

the pommel plate. It is interesting in this context that some mask swords do not have an upper ring, while others have complicated

constructions right below the pommel. Here are two examples: |

| | |

|

| |

|

Pommel plate attachment on my swords with (upper picture) and without (lower picture) a "ring"

construction

Note that the left-hand figure in the lower picture is not touching the pommel (marked by the arrow) ,

which is somewhat recessed at this place. Once more sloppy workmanship at places where you won't (normally) see it? |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The upper "ring" in this example (also visible in some of the swords

shown in one of the many Luristan modules) is more complex than the regular ones around the hilt, more a kind of decorative

band. As the pictures above demonstrate, it takes some tricky crimping to make a fit that looked "wie aus einem Guß"

(like from one casting) as we say in the true language.

|

|

Attaching the figures

Early

investigators laughed at the "primitive" crimping technique they encountered when they looked at Luristan swords.

They assumed that the old smiths had not yet mastered the art of fire welding for putting iron parts together in a solid

way. But crimping was the only option for the ancient smiths! As we have seen, at least some of the smiths could fire-weld quite well. However:

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Fire welding would have

destroyed the figures

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

Details would have burnt off at fire welding temperature, and banging on the

figures with a hammer wouldn't have done them much good either. |

|

Now what? There is no other way but crimping (if we discount modern

gluing or soldering) and that, if you think about it, is an exceedingly difficult thing to do.

|

|

|

First you had to produce the fittings or sockets for the figures (or the rings).

You needed to do some precision chiselling, producing the exact outline of the figures to be inserted. You can't do this

with the needed 1/10 mm precision if the the work piece is red.hot so you needed to do some heavy room temperatures deformation.

That is exactly what we see in one of the crimps

I claim that you can do this only with soft ferrite / mild steel as

a substrate. Hypereutectoid or just eutectoid stuff is hard and brittle and you just can't make those flawless (on the outside)

crimping joints we find. Note that you ruin your intended product if the crimp wall you raise with your chisel disattaches,

breaks, or gets otherwise disturbed. There is no easy fix if this happens.

Then you insert the figures and affix them

by "crimping", i.e. hammering the crimp rim over the figure base. This is not something

you do on the side; it must have taken a lot of practice to produce the perfect crimping we still see today. |

| |

| |

|

Optimizing the production process

Not caring all that

much for the "inside", i.e. slag inclusions etc., saves time and money. The same is true for the fitting between

the backside of the figures and the body of the sword. You can't see if there is a lot of empty space between the heads

/ animals and the pommel plate or the hilt. Perfect fittings would have called for a perfect match of the two surfaces to

be joined. We may safely assume that the artisans who made these swords would have had no difficulty to make perfect joints

or fits, too - but why go through the labor and trouble? |

|

|

I think it is likely that the old smiths also noticed that some of the sheets

they made as starting material for stack-welding were of inferior quality, containing large slag inclusions. But so what.

Just put them into the inside of a stack and nobody will know. Iron was very expensive, after all.

Now we have an explanations

why theses swords combine breathtaking workmanship with equally amazing sloppiness. The ancient smith had a modern attitude.

Making money was more important to them then impressing archaeologists some 3000 years later. |

| |

| |

|

Final Appearance

Luristan mask swords today are always more or less corroded and blackish to rusty in color. They are not a particularly

pretty or impressive sight. That was certainly not the case when they were new. If polished to a high sheen, they must have

been quite striking in appearance. |

|

|

But polishing everything would have tended to obscure the fine details of the

figures. My guess is that the figures were painted to some extent, outlining, for example, details (like the rims around

the eyes) in black or some other dark color. They certainly must have made a (fashion?) statement for the fighting man that

was not rivaled by much else available 2800 yeas ago. In Luristan, that had a very specific and very large range of (bronze)

weapons and an iconic art style (exemplified, for example, in the "masters of

animals"), these swords must have appeared as marvellous implements, but rather exotic in appearance. Not even

remotely related to anything else around.

My guess therefore is: |

| | |

|

| | |

Some Luristan mercenaries surviving

in the Assyrian army (cavalry?), took an iron

mask sword home with them when they

finally retired back to the old Homestead.

|

|

| |

| |

|

I have no proof, of course. But consider:

- Assyria had conquered 20 or more "kingdoms" in the general area,

and we do not have any idea of what kind of iron technology these kingdoms commanded. Nor do we know all that much about

heir religious believes. Some of those entities might well have promoted an art / religion that produced something similar

to the the iconographic heads and "lions" found on the mask swords. The general style of these figures certainly

is alien to the well-known Luristan style (or any other style found in the larger area during the time in question). A not

so common design made these things particularly attractive for the "tourists" (in the embodiment of soldiers /

conquerors).

- Assyria, as reasoned above, must have had a big and thriving iron industry. It also had a stratified society with rich

and powerful people who could afford useless but decorative and very expensive trinkets. The Luristanis, as far as we know,

didn't have all that.

- If the Luristanis did venture into iron technology at some (later) point in their metal-working history, one would expect

that they would have kept the basic design of their bronze stuff as exemplified in thousands of known artifacts. Indeed,

the iron Luristan swords of type II are quite similar to the bronze

types. The mask swords are not. .

- A civilization that has turned out thousands of bronze weapons (not to mention comparable numbers of bronze finials,

horse cheek pieces, etc.) and put it into the graves of their people, should have produce more than just a 100 iron swords.

- Maybe the iron mask swords were very expensive? Quite likely - but then you would have expected to find them in rich

graves of rich people. Nobody knows exactly where they have been found, but the robbed graves were all quite similar, no

hint of especially big or otherwise outstanding burials. This means that the owners of the mask swords had the same social

status as the many more non-owners. Well, the graves of the pensioned off mercenaries / warriors who by good fortune were

able to acquire one of the mask swords (or were given one for outstanding service) would not be much differernt from the

graves of their swords-less brethren.

|

| |

|

So why didn't we find Luristan mask swords in other places that once belonged

to the Assyrian (or Babylonian, if you like that better) empire? The answer is

simple and convincing: For the same reasons we found no iron whatsoever left over from

these empires (besides the Khorsabad hoard) even so we know for sure that a thriving iron industry must have been in place

(because of the Khorsabad hoard).

Why did we find far more Roman swords in Denmark (never part of the Roman empire)

then in the area the Roman empire (far, far larger than Denmark)? Well, the old Danes liked to go on tours, and like all

good tourists, they liked to bring something special back to the old homestead.

I rest my case. |

| |

| |

| Comparison With the

Literature |

|

How do our results from the cut sword compare with what can be found in the literature?

The straight answer is: |

| |

| |

| |

|

A lot of what we found has

been known before

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

However: almost all earlier investigations into the metallography of the mask

swords were restricted to very small samples making it hard to impossible to detect fire welding. Moreover, some of the

researcher harbored old and by now disproved believes (like the possibility of "carburizing" or "decarburizing"

bulk iron) that corrupted their interpretation. Our results shown here therefore do add considerably to our knowledge of

the Luristan swords.

Moreover, the journals then (as now) printed only

a few pictures at small sizes. Worse, print quality was not always very high and prints were only in black and white. Topping

all that is the sorry fact that what you see now in (often badly) digitalized copies of copies... is often just a faded

ghost of the original picture. That's why we "publish" here with lots of clear and often large pictures.

|

|

I shall now progress through the key publications from this list. An earlier "literary guide" is given here.

Let's start with the oldest of these papers: |

| 1 |

1957 F. K. Naumann: Untersuchung eines eisernen luristanischen

Kurzschwertes Archiv für das Eisenhüttenwesen, 28. Jahrgang, Heft 9, (1957) 575 - 581 |

|

|

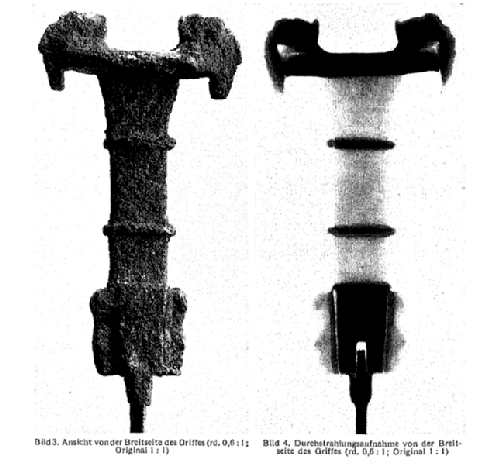

This is one of the earliest but still best papers to the subject. Small wonder,

it has been written in the true language by an expert metallurgist.

Naumann investigated the "Hamburg" sword and first dispels the believe that some iron casting was involved in

the making of the sword. Then he asks all the right questions about the making of the figures, the assembly of the parts,

the forging technique (fire welding?), the materials quality and so on.

Since the sword had to remain mostly intact,

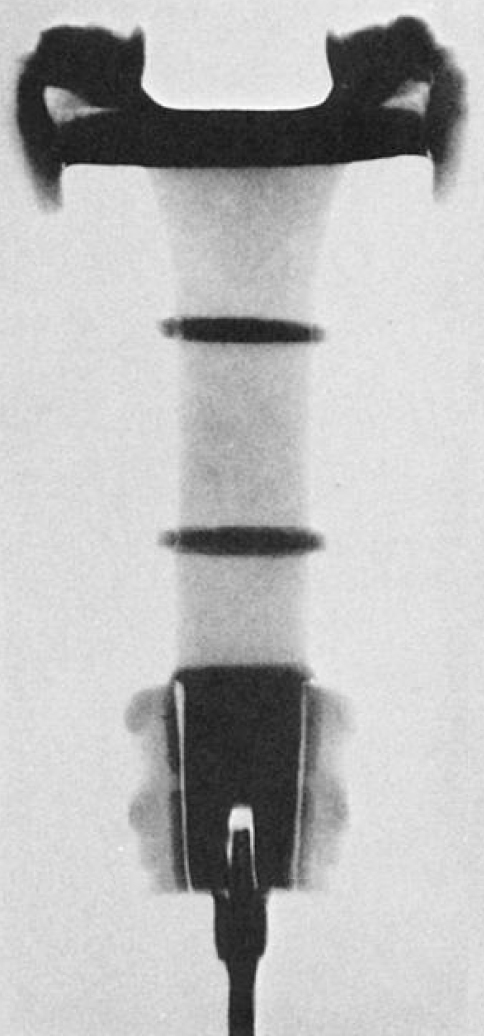

he employed X-ray techniques, or better said, g-ray techniques since he used the high energy

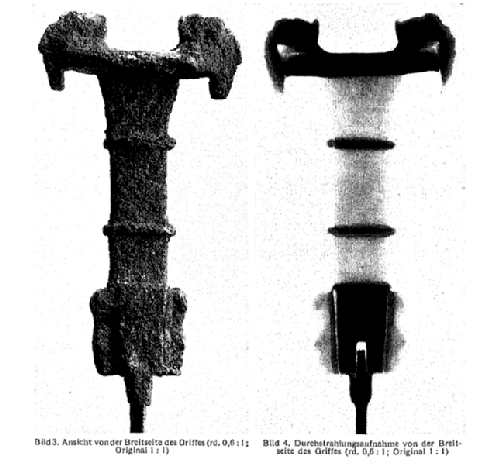

radiations of the isotope Ir 192. Here is an example of one of the many pictures he took: |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

The word Naumann investigated together with is X-ray image

Note the bad quality of the

picture now.

The originals were much better as we shall see |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

The picture is remarkable because it is the first "X-ray" image of

a Luristan sword. It (and its brethren) show the individual parts and their partially "sloppy" attachment. We

also see that the blade and the hilt were not made from one piece of iron (like our

cut sword) but were "stitched" together from at least two pieces. |

|

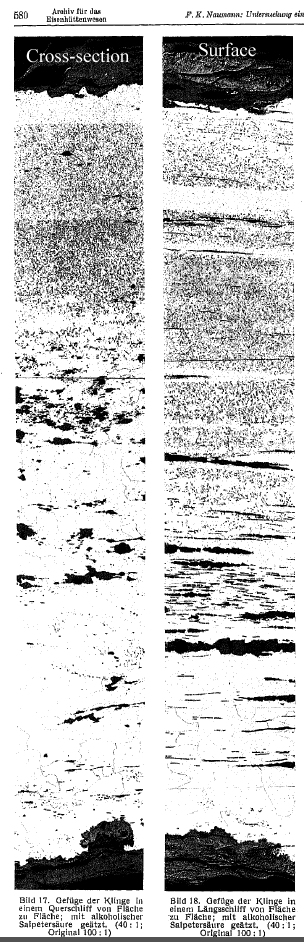

Naumann could investigate only very small parts of the sword metallographically,

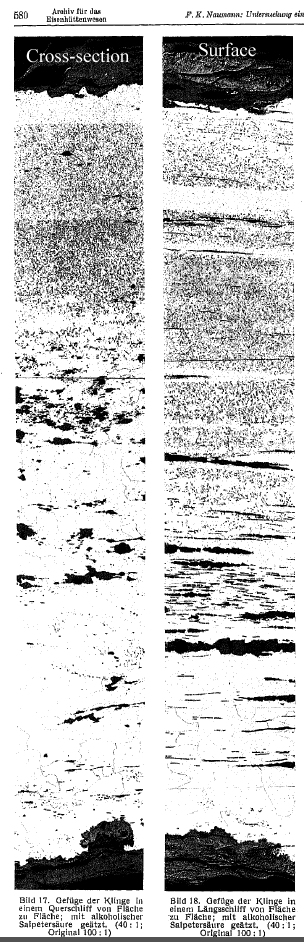

like an area of about 0.5 cm2 of the blade. The results are shown below: |

| |

|

| | Naumann's Nital etched sections of the blade |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

I show this picture to illustrate the point made above: You don't see much anymore

in present-day pictures of old publications. You do see , however, that Naumann's finding are quite compatible with ours. |

|

From the little he was allowed to do, Naumann drew many conclusions

that are also valid in our case. Here is a list

- No cast iron; the sword consists of many iron parts put together in a not always quite clear manner (for Naumann)

- It's rather unclear how the (in Naumann's case heavily corroded) figures were made.

- One is inclined to assume fire welding but Naumann's results were not yet conclusive for him (even so his blade investigations

do suggest this).

- The bulk of the blade consist of wrought iron / mild steel but parts of the (small) area investigate also showed large

carbon concentrations.

- Lots of elongated slag inclusion demonstrate some drawing out the material by forging

- Widmanstätten structures plus spheroidized cementite point to high temperature forging in an early state of its

making.

- Pearlite structures show medium temperature (700o) working at the end.

- Twinning (not observed in our case) hints at local heavy impact deformation at low temperature (e.g. by adjusting parts

by heavy hammer blows as required for scrimping)

- Chemical analysis shows relatively clean iron with mostly some C and Si, the latter most likely from the slag inclusions)

.

- You need to "destroy" a sword by cutting it apart if you want to answer the many questions still open. Namann

is all for doing that.

|

| |

| |

| 2 |

1961

Herbert Maryon;

with technical reports by R. M. Organ, O. W. Ellis, R. M. Brick, R. Sneyers, E. E. Herzfeldand F. K. Naumann: Early Near

Eastern Steel Swords,

American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 65, No. 2 (Apr., 1961), pp. 173-184 |

|

|

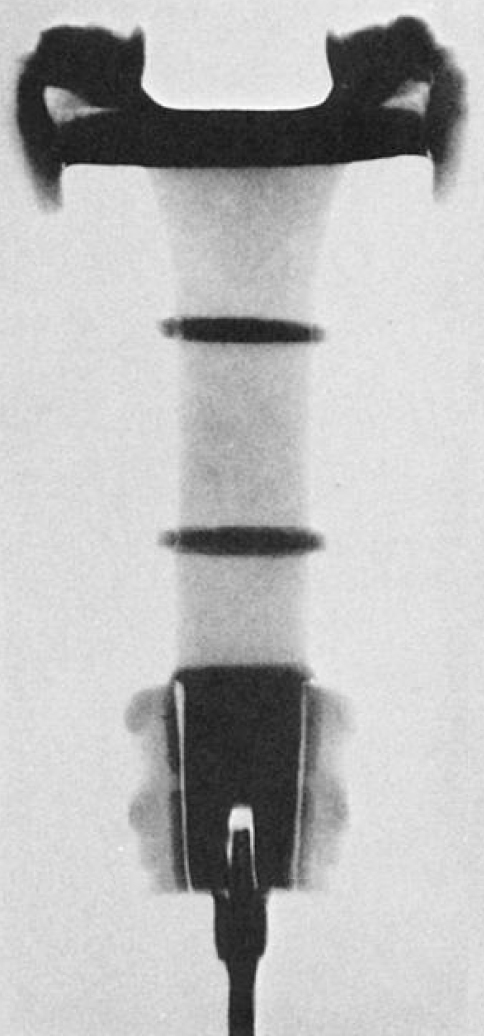

A key paper, reviewing the properties of 11 Luristan mask swords. The Naumann

paper from above is prominently featured, including some of its picture in much better quality than what is left from the

original. Here is an example: |

| |

| |

| |

|

One of the "X-ray" picture so Naumann's paper, in far better quality

than

in the original paper (see above) |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Compare to the picture above and you see the problem with pictures in old publications.

As far as the metallurgy of Luristan swords is concerned, Maryon reports on Naumann's finding and on metallurgical

results from the "Toronto" sword. Only small parts (the "beard region" of one of the figures) was investigated

in some detail, and the results are in line with what we found: High-carbon regions, some Widmanstätten structure -

an example is shown here, |

|

Maryons paper is interesting because he speculates about the origin

of these swords. Here are a few quotes

- No closely comparable material is known, and their place of origin has not been exactly ascertained,

though a number of the weapons have been found in tombs in Luristan.

- Although these works are generally recorded as coming from Luristan there is no evidence to show

that they were made there.

- The iron daggers are indeed a foreign element among Luristan bronzes, and though only one of the

specimens is known to have come from Pontus, that must be the original provenance of them all. In Pontus, iron, easily workable,

lies above ground."

??? Pontos is the area around the black sea and there are (ancient Greek) claims that iron technology originated there.

Maybe, maybe not. Certain is only that no elemental iron was lying around above ground.

- It is evident that at the time when they were being manufactured some very efficient workshops

must have been available, and that the separate parts of the weapons were mass produced. The sword may have been worn as

a badge of honor, awarded perhaps to some distinguished company of warriors for a notable deed of valor.

A version of my "trophy brought back from time spent as mercenary". |

|

|

Maryon might have been the first one addressing the problem of making the figures:

"The formation of the lions and of the human heads would have been effected first by forging,

then the finer details would be added by means of chasing tools and punches, for there is no indication of the employment

of cutting tools upon them."

He also realized that we are looking at supreme examples of craftsmanship:

"Just as the earliest books printed with moveable type are in many ways unsurpassed, so here,

the sword handles forged in the new metal, steel, by these pioneer smiths of the Near East, exhibit skill of a high order,

and no comparable steel sword-hilts have been found in any other land before the time of the Renaissance in sixteenth century

Europe." |

| |

| |

| 4 |

1966

K.

R. Maxwell-Hyslop and H. W. M. Hodges: Three Iron Swords from Luristan

Iraq, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Autumn, 1966), pp. 164-176

|

|

|

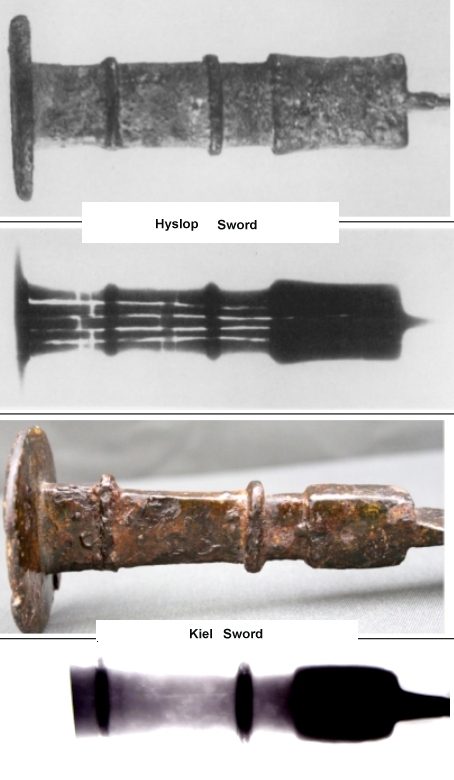

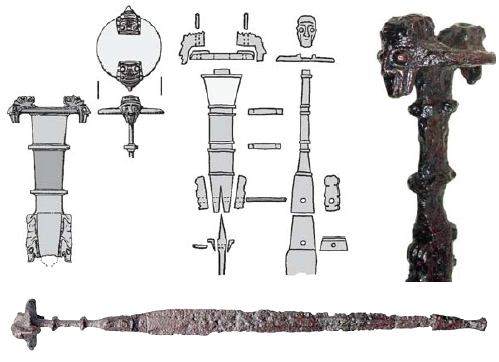

An important paper describing the first sword cut into two parts like ours. From

todays point of view this cut sword was rather atypical in its construction. Since nobody could know this at the time, its

unusual construction was assumed to be typical and dominated the structural discussion for a while. Look here and below for some details.

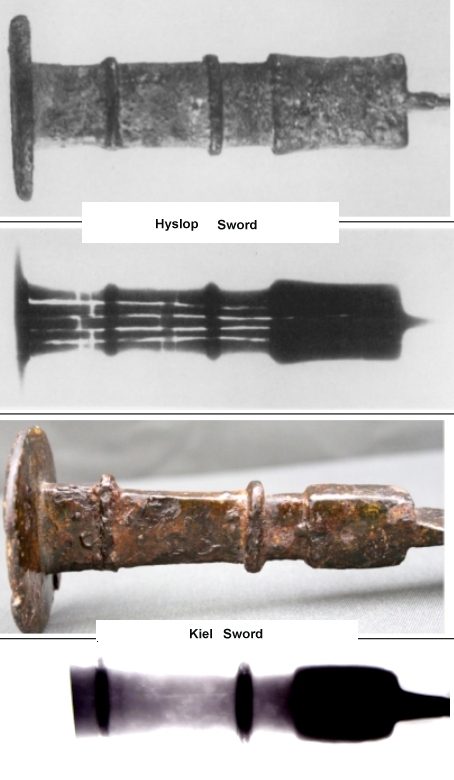

We investigated a rather similar sword and found

that it was much simpler in construction, rather more like our cut sword (just without figures etc.) Here is a comparison: |

| |

| |

| |

|

| | Maxwell-Hyslop sword plus X-ray and Kiel sword plus X-ray |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Note that the hilt of the Hyslop sword actually consists of a stack of "thin" sheets.

Fire weld the stack and you have what we found. |

|

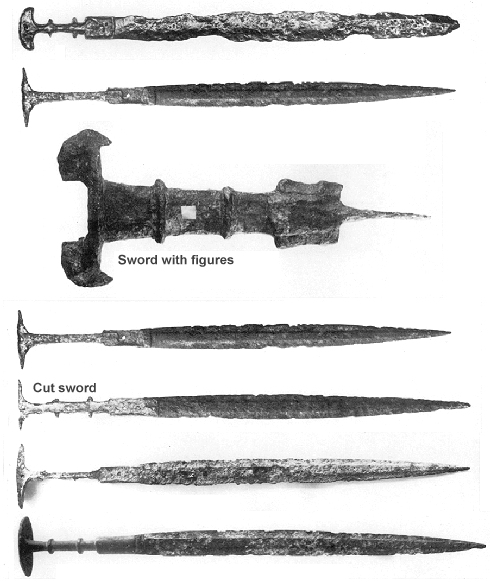

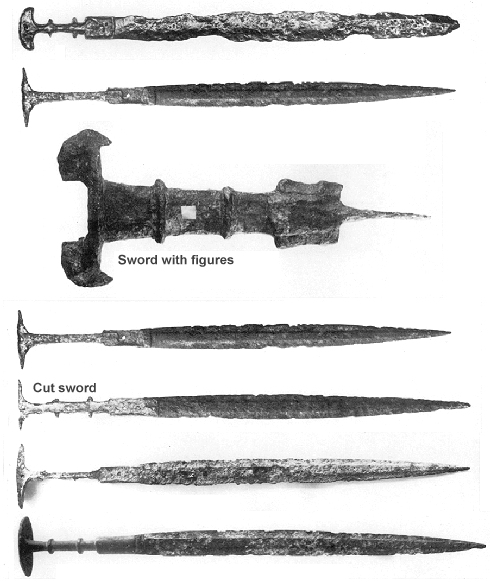

Beside the cut sword several others were investigated, all of them but one without

figures and therefore probably earlier than our cut sword. The set of swords investigated is shown below: |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| The sword investigated by Maxwell-Hyslop and Hodges. Note that the uppermost one looks rather

like a Luristan type II sword |

|

| |

| |

|

The sword with the figures led to some insights:

- The blade and the grip are a single piece of metal.

- The two seated lions forming the guard, and the pair of bearded human heads facing outwards, with

lions' heads facing inwards, that decorate the pommel have been applied by fitting them into recesses formed in the metal.

Here again adhesion of the applied parts has not been achieved by heat welding, but by burring over the edges of the recesses,

a process already fully discussed elsewhere.

- Close examination under the binocular microscope showed the presence of a number of areas in which

copper corrosion products were present. At first it was felt that these were due to contact

with corroding bronze objects, but a closer inspection revealed that iron corrosion products from the weapon itself overlay

areas of copper corrosion, and one is forced to conclude that areas of this hilt may have been covered with a copper alloy

The only hint in the literature of some finish of the swords. A bronze coating doesn't make sense, however. Why coat a figure

made in a tiresome way from iron with bronze, if it would be far easier to just cast one?

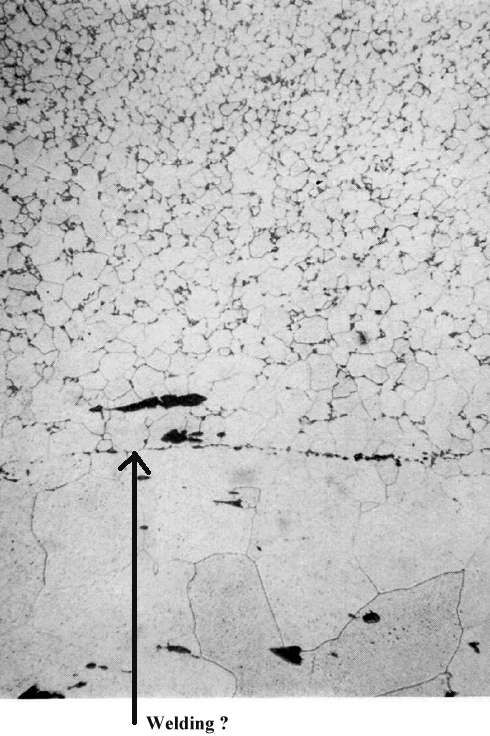

The microstructure analysis of small areas from the sword with figures are consistent with ours. Slag inclusions,

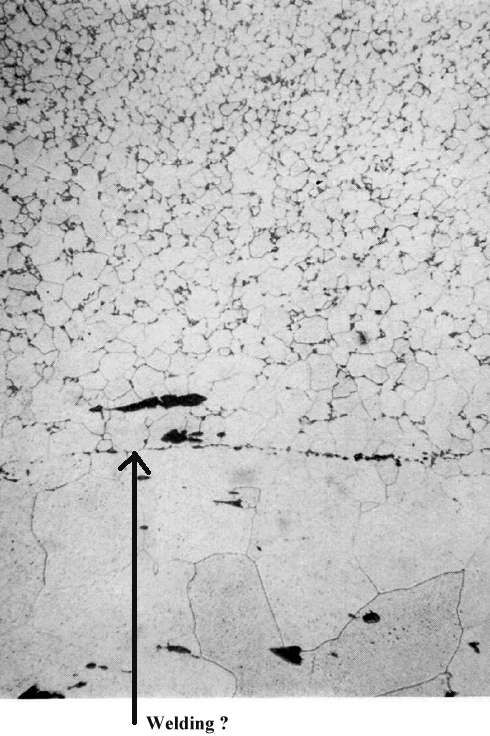

areas with low and high carbon concentrations, and so on. One picture may even show a fire-welding interface: |

| |

|

|

A possible welding boundary from the sword investigated by

K. R. Maxwell-Hyslop and

H. W. M. Hodges |

|

| |

| |

|

However, the authors completely misjudged the sword production process:

- "A competent blacksmith does not rely upon rivets and bands and burred edges to hold his

work together; he uses, rather, a hammer weld carried out in the hot."

No, he wouldn't! That would destroy

the carved figures!

- "To be blunt, seen in terms of black- smithing these swords are a mess, and any of them could

have been better made by the barbarian smiths of central Europe, certainly by the eighth century B.c. "

- Certainly not. They were also not made for fighting but for showing off.

- "Equally, the fact that, in certain cases, the iron had become carburized does not of itself

argue that the makers were intentionally converting some of the iron to steel, but only that the metal was being subject

to long, or frequent, periods of heating in carbon."

Wrong.. There is no substantial carburization ever during forging.

- "It is precisely the incompetence of the smiths that is so interesting: they had so obviously

not fully realized the potentialities of the metal they were working. In fact, when one looks critically at the methods

of manufacture employed-the use of flanges to hold insets, the punch technique of decoration, and the final planishing-one

is reminded as much, if not more, of the bronzesmith than the blacksmith."

Wrong. Just try to forge an iron

mask sword with all the modern tools and methods and you will find it rather difficult. |

| |

| |

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)