| | |

Early Iron Swords |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

| | |

|

| |

|

The Hittite sword from 1300 - 1400 BC |

|

The backbone contains a lot of information regarding early

iron artifacts - so why this module? Here is why:

- I'm writing this module years after the backbone one and meanwhile I have learned more.

- The backbone module focuses on famous (or infamous) "first iron" from before 1.200 BC - and most or all of

that stuff was now found to be meteoritic in origin. Here I focus on more or less unknown

pieces from before 600 BC, let's say, that were made from smelted iron. And I'm not

interested in "small fry" like needles

or rings but only in complex artifacts that took some extended smelting and forging

technology to make - swords, in other words.

- I will use this module to systematically include new "finds" that might come up in the future.

- Lately I got heavily involved with the "Luristan mask swords"

(which meet the criteria outlined above), and this module serves as a kind of connection to the enigma inherent in these swords.

I'm an amateur and not an authority on the topic. Ünsal Yalçin,

whom we have encountered frequently before, is an authority on the topic and that's why you should read his article "Zum Eisen der Hethiter" first. You might have to learn

German first, though (always a good idea). You also might want to consult Jane

C. Waldbaum's

long paper: The Coming of Iron in the Eastern Mediterranean".

Or you read on; I will give you some of the information contained in the articles right here.

What I'm going to show

in what follows is: |

| |

|

| |

|

Iron use in bulk started around

800 BC. Before that iron was

a exotic and precious material,

like Aluminum after 1850 .

|

|

| | |

|

|

|

Aluminum was first produced in 1824. Mass production of cheap Al did not start before about 1890. In between

Al was precious. Emperor Napoleon III of France employed aluminium plates for state dinner because it was mire precious

than gold, The top of the Washington monument in Washington (finished 1885) sports a 2.4 kg aluminium cap. Impressive stuff

(like the iron dagger from Alaca Höyük

or the iron axe from Ugarit) but not implying that

the material was of any importance in daily life. |

|

Three topics in Yalçin's article are of interest in the context of this

module: |

|

|

First, Yalcin assumes - like everybody else - that the Anatolians, mainly during the

time of the Hittite empire, were the first producers of iron, i.e. smelting the stuff

and not just relying on meteoritic iron from somewhere. Then Yalcin points out that

there are less then two dozen iron artifacts known from the Hittites;

mostly small things. There are hardly any metallurgical investigations of these small items, so some or perhaps nearly all,

might be meteoritic in origin. |

|

|

Second, Yalcin goes into some detail about the written record concerning iron from

Anatolia. Much of that can also be found here. What emerges is that iron was an

extremely expensive commodity around 1800 BC, say, but became relatively cheap in 1200 BC or thereabouts. |

|

|

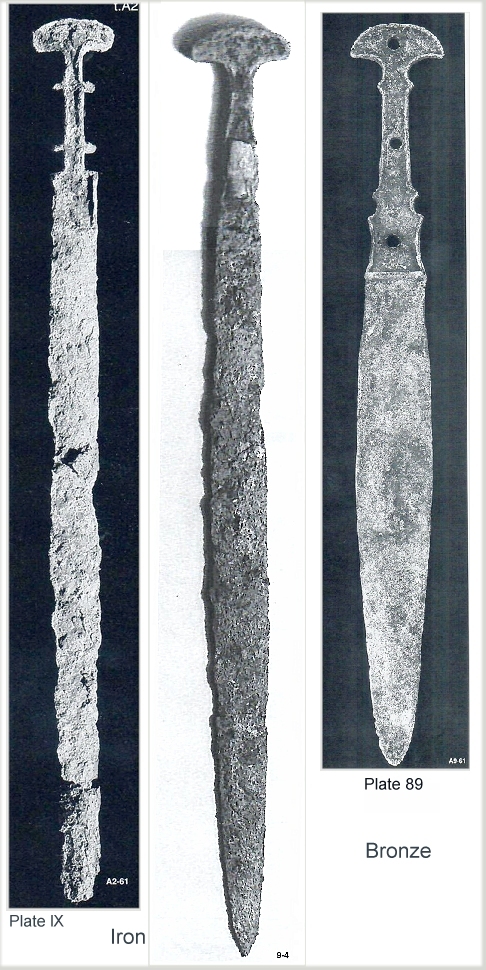

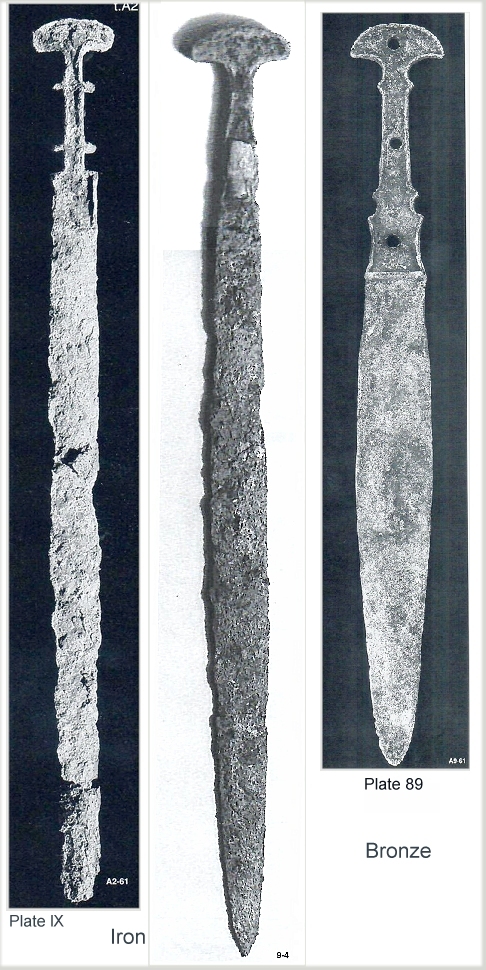

Third, Yalcin introduced a veritable sword from 1400 BC - 1200 BC that was made from

smelted iron as shown by a metallurgical analysis. It is the one on the left in the

picture below.: |

| |

|

|

|

|

Left: Hittite (?) iron sword. Ruhrland Museum Essen, Germany

Midde: Sword up for sale (Feb. 2021) designated "Western Asiatic Luristan Sword with Bronze Hilt 13th-7th century

BC"

Right: Luristan dagger with similar hilt |

| Source: Wikipedia and others |

|

| |

|

|

The sword on the left - let's call it the "Essen

sword" - woulöd be the oldest known "complex" artifact made

from smelted iron. I'm discounting the Alaca

Höyük Dagger, King Tut's dagger,

the axe from Ugarit, and so on, because, according

to A. Jambon (and others

before him), all these complex objects were made from meteoritic steel. |

|

|

Yalcin goes on in this paper

and presents for the first time a metallurgical analysis of this alleged Hittite sword. I'm saying allged because it is

the only object whose provenacne is given as "?"on a long list of iron objects from Anatolia as given in Yalcin's

paper. In othe rwords, it does not come from a scientific excavations but from an unclear sources. Yalcin points out that

it was fire welded from several pieces of steel with varying concentrations of carbon. The metallographic pictures also

seem to indicate that there aren't large inclusions of slag and other smelting debris. Are we are forced to conclude that

between 1400 BC - 1200 BC somebody somewhere in present-day Anatolia could produce a complex

steel object by first producing a qualitatively decent bloom by smelting, and second, by employing rather involved forging

techniques? |

|

Now look at the sword again. It does remind one of bronze swords but you will

not easily find a well-matching bromze sample. The right-hand picture shows the closest match I could come up with. This

dagger was offered and sold on e-bay in 2017, and described as bronze / iron dagger from Luristan, 1.000 BC.

The hilt

part is reminiscent of finds from Luristan / Amarlu (see examples around p. 400 in Khorasani's

book). Note that its iron part is fairly complex; some experienced smith must have shaped the blade, fire welding pieces

of iron and drawing them out to a pleasant shape. |

|

|

Forging alone, however, could not produce the smooth shape of the blade. So grinding

and polishing the blade to the perfection still visible must have been used. Moreover, the 5 ridges in the blade center,

flaring apart close to the hilt, must have been formed by "cutting" the iron,

using sharp and hard but delicate tools.

All these techniques, except for the forging, were known to some extent from

the bronze technology. Nobody, however, had ever made a bronze blade by banging a lump of bronze metal into shape. |

|

Unfortunately, no detailed information about the sword - who has found it when

and where?, how was the dating done? - seems to be available right now. While there is no reason not to trust the dating,

there is also no reason to just accept it without some independent confirmation. What's more, swords like this are around

in the antique trade, the middle picture shows a recent example from "Timeline".

The long and short of this is quiter clear:

|

| | |

|

| |

|

The "Ruhrland Museum Essen, Germany"

sword does not count until further

evidence of its origin is provided

|

|

| | |

|

|

Now it is 2021 and further evidence has not been provided. On

the contrary, there is evidence that this sword is from the 9th / 8th century BC. Jens

Nieling on page 44 of his thesis writes:

"Ein eisernes Schwert das in Essen aufbewahrt wird, wird von Yalcin 2004 als hethitisch ansgesprochen.

H. Tsumoto konnte 2005 in London überzeugend zeigen, dass es sich vielmehr um einen

Waffe des 9. / 8. Jh. aus Luristan handelt" |

| |

|

H: Tsumoto has published much on the topic (i.e. to Hittite and Uraturian

iron technology / swords) , but I could not find the exact reference (not given in Nieling's work). I tend to believe his

claim, however. |

| | |

|

| | |

Early "Mediterranean" Swords |

|

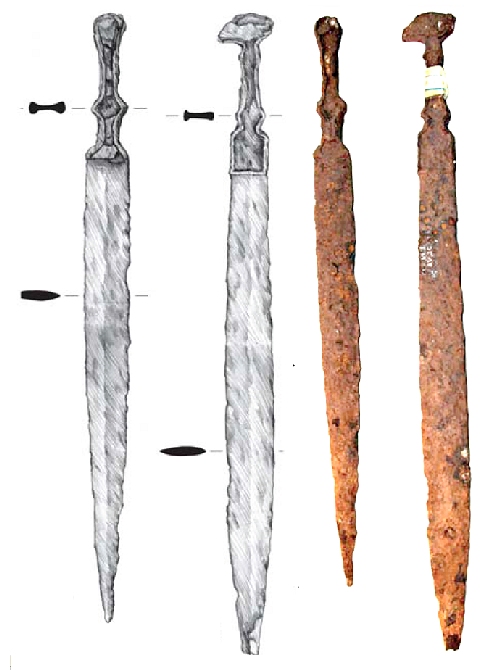

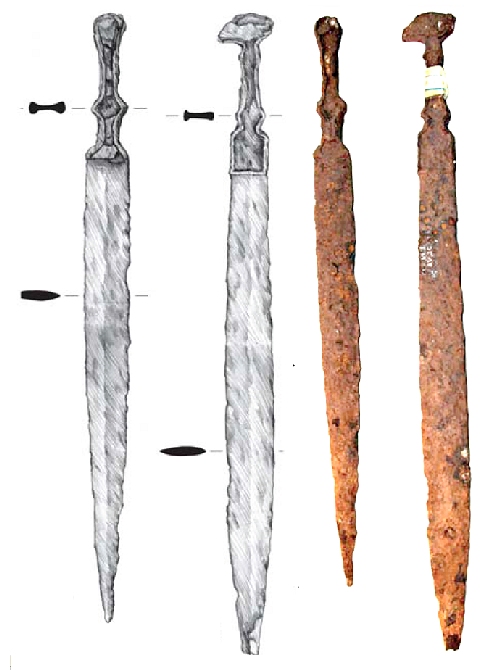

Below are three swords of interest: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

Old iron swords from around the Mediterranean

Scales somewhat different

|

Source:

1: From B. Overlaet, one of the authors of a poster 1);

2: Photographed in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, Nov. 2017;

3: From a 2017 advertising in e-bay. Now in the

Brussels museum |

|

| | |

|

|

|

No. 1 is from Saruq al-Hadid, a place way down on the Southern Dubai coast and described in a poster 1). It's age is somewhat

vaguely given as 1200 BC - 300 BC. While found 800 km or so south-east of Luristan,

the sword (and a lot of similar iron artifacts found there) are believed to have their origin in Luristan, suggested by

involved analysis of trace elements.

The poster makes an earthshattering claim substantiated by later papers (for details

use the newer science modules dealing with the topic): |

| | |

|

| |

|

These swords were forged by using

faggoting / piling!

|

|

| | |

|

| |

|

No. 2 is a "ceremonial sword", on display in the Israel

Museum in Jerusalem. Its age is given as 7th century BC. It was excavated in Vered Jericho. That is all the information

the museum provides right at the (badly displayed) item. The Internet, however, knows more.

First of all, its age is

rather definitely 600 BC. That makes this sword almost too young to be included here but I'll keep it nevertheless. Here

are some excerpts from information the museum has provided in the Israel Museum Journal of 1992: Microradiographic

x-ray examination and photography of the sword indicate that the hilt, ridge, and the blade were prepared separately and

then forged together by hammering. Metallurgical analysis of a sample taken from the blade proves that it was made of mild steel,

and that the iron was deliberately hardened into steel, attesting to the technical knowledge

of the blacksmith. That statement is nonsense, of course. |

|

|

No. 3 is a sword that is presently (Jan, 2017) on sale by Zurquieh Co. LLC, based in

Dubai. It is described as "ancient Luristan iron sword from 1200 BC - 700 BC. It looks a lot like No. 1 and we might

confidently assume that it comes "somehow" from Saruq al-Hadid, too. |

|

Next, a Greek sword from around 900 BC. It is wrapped around a funeral urn and

displayed in the "Museum of the Ancient Agora" in the so-called "Stoa

of Attalos" building in Athens. The Museum provides the following explanation: Finds from an

early geometric cremation burial of a warrior craftsman. About 900 BC. 1 - 2: ash urn (neck amphora) and iron sword; 3:

iron set of horse bits; 4: iron pin; 5 iron fibula, 6: iron chisel; 7: iron knife; 8: iron axe; 9-10: iron spearheads.

Below you just see the sword and the picture is turned by 90o to make comparison to the picture above easier.

Use the link to see the other stuff, too. |

| |

| |

| |

| Old iron sword from Greece

Other picture |

| Source: Photographed in the Museum of the Ancient Agora, Athens, 2017

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

900 BC makes it rather old. But again, while there is no reason not to trust the dating given

by the museum, there is also no reason to just accept it without some independent confirmation.

As far as one can tell

from these pictures, the 4 swords are rather similar in appearance, and that is particular true for the hilt part. This

may be no accident since they might all have originated in the same place: Luristan! |

|

To prove that tall claim we now look at some swords that were

actually excavated in Luristan and date to around 800 BC or a bit earlier. I'll call them "Luristan type 2" swords just to be able to refer to them easily. The mask swords then would be type

1. |

| | |

|

|

|

| Two Luristan iron swords and a bronze

sword / dagger for comparison |

| Source: Left and right from 4), middle

from 3) |

|

| | |

|

| |

|

| Two iron swords from excavations at a Luristan sanctuary

More pictures here |

| Source: 3) |

|

| | |

|

|

I don't have numbers but quite a few of this particular kind of sword have been

found in Luristan or in the Dubai "outpost". So it is quite possible

that these swords originated in Luristan and were traded far and wide. Only future research will tell. |

|

|

We are left with even more puzzles. To enumerate a few:

- While all 100 or so mask swords came form illicite digging early in the 20th century, no type 2 swords seem to have

hit the market. Either they weren't found or deemed unfit fore selling.

- While archaeologists by now have excavated 100+ graves (and "treasure pits" in sanctuaries, they have not

yet found a type 1 mask sword in-situ. They did find plenty of bronze daggers, large amounts of pottery, a few "master

of animals" idols, jewelry, and several type 2 swords.

- The type 2 swords are closely related to bronze type swords / daggers while the mask swords bear no resemblance whatsoever

to bronze things,.

- Type 2 swords have been found outside Luristan (possibly trade items) while mask swords so far seem to come only from

Luristan

- Type 2 swords are all (?) heavily corroded. Most type 1 swords are also heavily corroded but there are a few very well prevered ones too.

It just doesn't quite match. There is potential for future research. |

| | |

|

| | |

Early Celtic Swords |

|

There are plenty of Celtic iron swords from the La Tène period (450 BC

- 0), and a few from the Hallstatt period (800 BC

- 500 BC). They have very distinctive shapes and are extensively covered in the backbone

module. Below two rather unusual Celtic iron swords are shown: |

| | |

|

|

|

| | Unusual old Celtic iron swords |

| Source: Hermannn Historica Auction catalogues; see below |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Both swords were up for sale on auctions. The descriptions given were:

No 1: Auction Catalogue "Hermann Historica" 2017. Text: Iron Age Early British Celtic Sword; 12th

- 10th century BC. An iron sword copying a typical pattern of the late Bronze age period, of generally Ewart

Park form, ....

No. 2: Auction Catalogue "Hermann Historica" 2015. Text: "Eisernes Griffzungenschwert" (Naue

II), South-East Europe, 8th century BC |

|

The swords are nearly identical and thus belong most likely to the same period.

That leaves us with 8th - 12th century BC. They certainly look like the bronze "dual use" sword type shown here.

Last, another old and remarkable Celtic sword: |

| | |

|

| |

|

Old Celtic iron sword; Hallstatt

type

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden

Another picture is here |

| Source: Interent at large |

|

| | |

|

| |

|

This is the famous "King of Oss" sword discovered in 1933 in Oss, Netherlands. It

is dated with some authority to 700 BC.

Note that this sword was forged by highly skilled smith. At this level of perfection,

one must assume that the smith's work was based on the accumulated experience of generations of smiths and iron makers that

preceded him. It is, in other words, rather unlikely that our smith and his buddies invented the smelting of iron, the treatment

of the bloom, and the forging of a sword during their own lifetimes

Also note that this blade has also been ground,

polished, and "cut" by experts, and that its hilt part also testifies to rather advanced techniques and designs

that were not developed overnight.

A close relative was shown in the 2018

special exhibition "Faszination Schwert" in the Württemberg State Museum in Stuttgart. |

|

That's it. My whole collection of complex iron items from before 600 BC, not counting

Luristan mask swords. To be sure, one could probably find a few more Hallstatt type Celtic swords or more of the same for

everything above. There must be scores of old rusty swords from before 600 BC in the basement of museums and occasionally

even somewhere in the back of a cabinet in the exhibition. But it's likely not going to be a lot

more, and it's just as likely not going to be quite different. |

|

|

Did you notice that we have an unexpected surprise here? No? Well - I have shown you 8 swords.

Three are from the Celts and they are possibly somewhat older than three of the other ones. But the Celts appear on the

scene some 400 years after the "official" beginning of the iron age in 1200 BC and are supposed to have learned

iron technology from others |

|

Let's summarize. What can we learn from this collection of complex

iron items (=swords) from before 600 BC? |

|

|

First, all of them are similar in the sense that they

are modelled to a large extent after bronze swords. That is what one would expect. Artisans in their right mind, when switching

to a new and difficult material, would tend to keep everything else as close as possible to time-honored designs and structures.

The Celts in particular have made swords like the one right above in a range of materials.

Second: Artisans in their right mind would tend not to make a radical change in technology

at all. If they switched to iron, they were either forced to do that because bronze was no longer available or because they

had realized that the new material actually provided some advantages. It takes some entrepreneurs to figure that out, but

eventually the know-how is there. The major challenge (besides making the iron by smelting) was the need to forge

it into shape instead of casting. That needed some experimenting and then a lot of practice.

However, as soon as you had mastered the art of forging to some extent, you noticed that you now had a tremendous advantage:

You could easily make all kinds of shapes: you didn't need a difficult-to-make mould every time you wanted to change something.

Moreover, the process was very forgiving. You could correct mistakes up to a point, and you could actually recycle

the material easily. Just bang it into a lump again and start afresh.

Third: With halfway decent iron or steel, you could make the blades longer than with

bronze. They might bend and wobble when something hard was hit, but the danger of breakage might well have been lower than

with comparable bronze swords.

Fourth: It is generally assumed that all those cultures around the Mediterranean before 600 BC had an iron technology that was better in quality

and / or quantity than that of the Celts in Europe after 600 BC. It is then assumed

that this superior iron technology diffused from the East to Western Europe and enabled

the Celtic iron works. The question then is: What, exactly, diffused? So far we haven't seen anything early in the East

that was superior to the later Celtic stuff in the West. The smith who made that Hallstatt sword shown above could not learn

much from his colleagues who made those Mediterranean swords. Could it be that we owe advanced

iron / steel technology to the Celts? Have they come out of Luristan?

Fifth: The Luristan mask swords,

believed to be from around 700 BC but possibly considerably older, do not fit into all

of this! They are more complex than all of the above and they are completely different in looks and composition from any

other sword or dagger, made from iron, bronze or a combination thereof, that are known from this time horizon. this time horizon.

|

| | |

|

| |

|

-- to be continued -- |

| | |

|

|

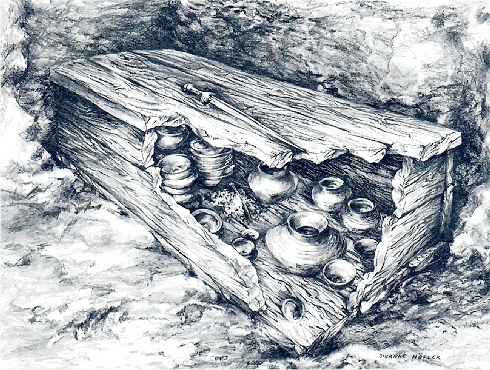

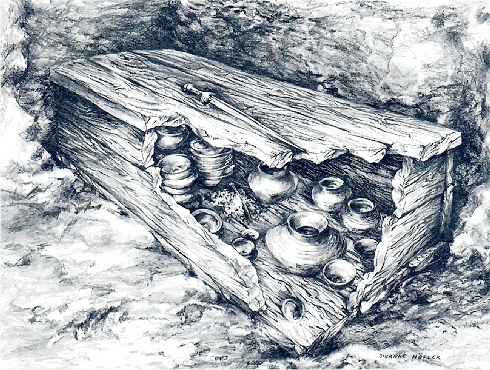

Shortly after I wrote all of the above, I ran across another

old Celtic iron sword, in fact the oldest iron sword

in (Middle) Europe according to the people who investigated it.2) Here are both articles of interest in

this context. The sword was found in a Celtic grave in Singen, a town in Suebia (of

course). it was a substantial grave, dating to the "second half of the 8th century BC", i.e. to 750 BC - 700

BC. It was put on top of a wooden box or coffin that contained the ashes of the (burned) person plus ceramics and some other

small stuff. Here is an artists conception: |

| |

| |

| | |

|

| Artist conception of the Singen burial. The sword was put on top of the wooden coffin |

| Source: Article preceding Ref. 2 |

|

| | |

|

|

|

This picture was done by Mrs. Susanne Höfler and shown in the article of Wolfgang Kimmig

about the grave in general that precedes this one. What remained of the sword is not spectacular

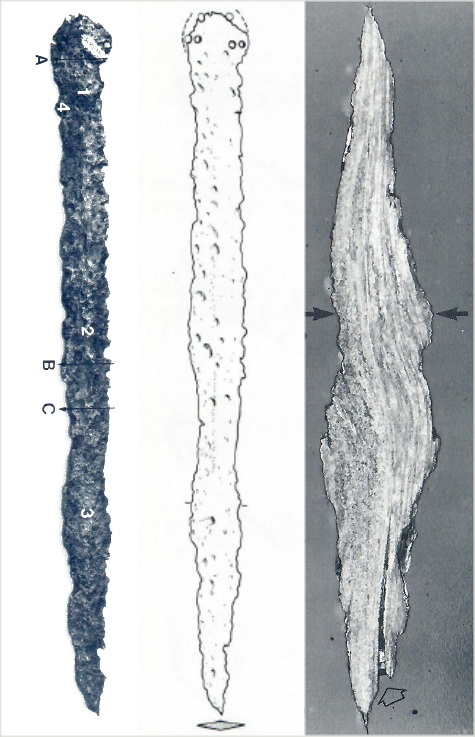

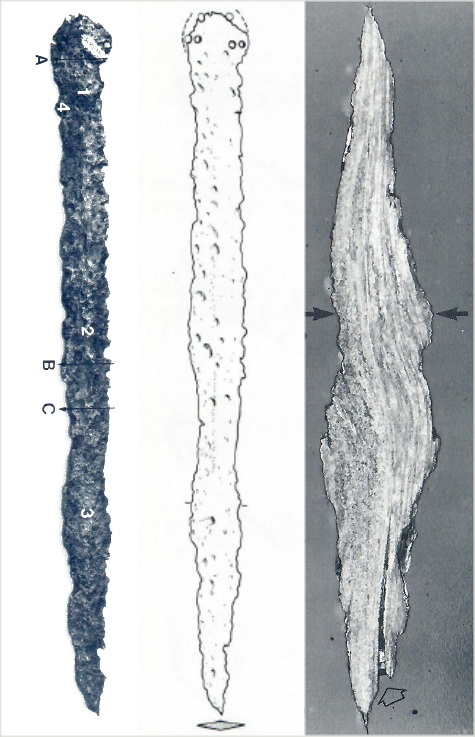

but nevertheless quite interesting. In the picture below you can see why: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| Actual sword of Singen, tracing, and etched cross-section (from position B) |

| Source: Reference 2 |

|

| | |

|

|

Can you see it? That the sword was very likely forged by utilizing faggoting, i.e. repeated folding and drawing of the material? The "famous"

Japanese way of sword forging some 1500 years later? The structure looks rather

similar. |

|

|

The authors of the article provide more pictures of the microstructure of the sword; see the

article if you are interested. Like all "very old" steel,

it shows strong variations of the carbon content, sizeable inclusions of slag, etc. The major conclusion thus is:

|

| | |

|

| |

|

Faggoting was known in Northern Europe before 700 BC

|

|

| | |

|

| |

|

That is a major statement! |

| |

| |

| | |

- to be continued - |

| 1) |

Ivan Stepanov, Lloyd Weeks, Filomena Salvemini , Kristina Franke, Charlotte Cable,

Peter Grave, Olivier Alard, Bruno Overlaet, Peter Magee, Yaaqoub Yousif Al Ali and Mansour Boraik Radwan:

"Understanding

the earliest use of iron in South-eastern Arabia: Invasive and non-invasive archaeometric approaches to the ferrous remains

from Saruq al-Hadid, Dubai"

Conference: 9th International Conference on the Beginnings of the Use of Metals and

Alloys, October 2017

Here

is the Poster shown at the conference |

| 2) |

P.O. Boll, T.H. Erismann and W.J. Muster, Dübendorf: "Metallkundliche Untersuchung

eines frühen mitteleuorpäischen Eisenschwertes", in : "Frühes Eisen in Europa", Festschrift

Walter Ulrich Guyen zu seinem 70. Geburtstag; Herausgeber H. Haefner; Acta des 3. Symposiums des "Comité pour

la sidérurgie ancienne de l'UISP", Schaffhausen und Zürich, Okt. 1979, S. 45- 51.

The preceding article

of Wolfgang Kimmig discusses the grave finds in general. |

| 3) |

M. Malekzadeh, A. Hasanpur, Z. Hashemi: "Fouilles (2005 - 2006) à Sangtarashan,

Luristan, Iran", Iranica Antiqua, Vol. LII, (2017), pp 61 - 185.

The paper reports on a large number of objects

found "hidden" in the floor of a kind of temple / sanctuary |

| 4) |

B. Overlaet: "Luristan excavation documents, Vol. IV; The Early Iron Age in the Pusht-i

Kuh, Luristan", Acta Iranica, Vol. XXVL, 2003; several 100 pages, not succeisvely numbered. See

also this link. |

| |

|

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)