| |

A Brief History of Steel

|

|

This moduel is also availabe in Romanain languga, thanks to

Irina Vasilescu. Here is the link |

| |

|

|

This is a much embellished translation of an earlier version

written in German (it can be found in the Hyperscript "Matwiss

I") and with some footnotes added later.

If you really want to know about the history of iron and steel use

this link. |

|

|

|

In order to make steel

not accidentally, but conscientiously, you obviously first need to make iron. In

contrast to the noble metals like gold, silver or platinum (and the occasional find of pure copper), iron is never (?) found as an element but practically always as an oxide. |

|

|

However, in contrast to other metals found as oxides (especially Cu and

Sn oxides needed to make bronze), the temperature of a "normal" fire is not sufficient to reduce iron oxide

and to make the elemental iron liquid - the melting point of iron is Tm(Fe)

= 1535 0C; far above the (1000 - 1100) 0C that the ancients could produce (?). |

|

|

For Copper (Cu), e.g., it is different

- its melting point is Tm(Cu) = 1083 0C. Throw some copper minerals in a nice hot fire

made with plenty of charcoal (producing CO which is great for reducing oxides), and liquid copper will result almost automatically.

|

|

|

This happened and was noticed probably a good

6000 years ago, when early potters tried to adore their pottery with nice green malachite

- a copper mineral known in antiquity and used as a gem

stone. What a surprise, when one day in a particularly hot fire, instead of decorated pots they found an ingot of pure

- and then extremely precious - copper in their oven. Copper was otherwise only found in small quantities (much less frequent

then the (then) ubiquitous gold) in mountain ranges and river beds. |

|

This was a decisive discovery for mankind: Precious and shiny metals could be

made from dull stones. Things could be changed from one seemingly immutable form into a completely different one - alchemy has its roots right here, and the yearning for "transmogrification" has never stopped since. |

| |

|

|

Early metal industry and the short-lived "copper age"

began to be replaced rather soon by the bronze

age (Cu + (5 - 10)% Sn and often some As); and the bronze age lasted more

than 2000 years (it was not abruptly replaced by the iron age, but coexisted for about 1000 years).

| |

|

From the "Kieler Nachrichten", front page, one day after after I wrote this paragraph. It says:

On the Track of Charcoalers

Up to the 16th century, Schleswig-Holstein was woodland. Then the trees were

felled to produce charcoal (among other things). How that is done will be demonstrated by Stefan Brocke in the Loher woods. |

|

|

|

Here we first encounter the importance of impurities: A little bit of As as an impurity

atom makes bronze "harder", it doesn't deform so easily any more. Of course, nobody knew this. All that was probably

known was that some sources of copper and tin ore, together with all kinds of tricks (including some magic or prayers, of

course) produced superior bronze. |

|

|

It is quite natural that tin and other metals were discovered shortly after the momentous

discovery of copper smelting. Once you saw that precious copper could be made from some kind of rock, everybody not completely

stupid would of course try what you could get with other rocks. |

|

|

We also have the beginnings of an environmental disaster, because for metal smelting you need

tremendous quantities of charcoal. First in order to obtain high temperatures but, just as

important, for reducing the metal oxide according to |

|

| | |

| |

| |

|

| | |

|

|

|

About 100 kg

charcoal are

needed to smelt 5 kg of copper. |

|

|

Besides shipbuilding, charcoal production is responsible for the disappearance

of large parts of European forests (the disappearance of yew trees (which were ubiquitous in antiquity) from present day forests, by the way, is due to the

middle age bow-and-arrow industry - nothing beats a yew bow!). Charcoal production was a major industry and the source of

the many charcoaler

("Köhler") stories in fairy tales and folklore. |

|

|

Beside Cu and Sn, Pb, Hg, Ag, and of course Au, were

known and produced on an industrial scale - especially by the Romans. But the Romans (and the Chinese, and the Indians,

and the ...) had also Fe - but still no fire hot enough to melt it. |

|

Early experience with the smelting and melting of other metals did not help in

producing iron - it first came into use about 1000 years later than bronze. This must have been a kind of puzzle,

because the ancients did know that iron existed. It was extremely rare

and precious - because it fell from the sky in exceedingly small quantities. |

| |

|

|

|

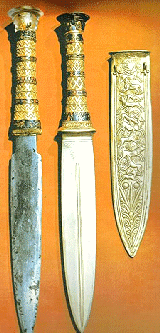

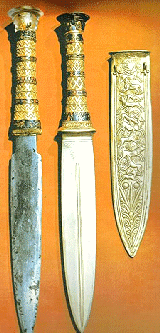

King Tut, matter of fact, had a little iron dagger

made from meteorite iron right on his breast - obviously his most precious object. In old Sumeria, iron was called "sky metal" and the pharaohs in old Egypt knew it as "black

copper from the sky". | |

|

|

| King Tut's daggers (Internet source "Stacey") |

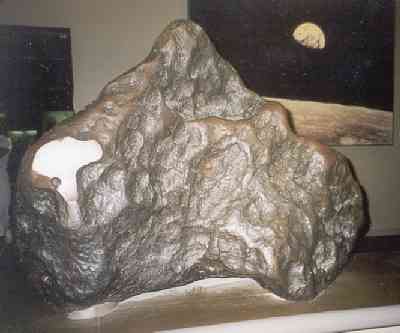

Meteorite stolen from the Eskimos |

|

|

Of course, only pictures of his less precious and useless but more showy gold dagger are easy

to find. The picture on the right shows both. |

|

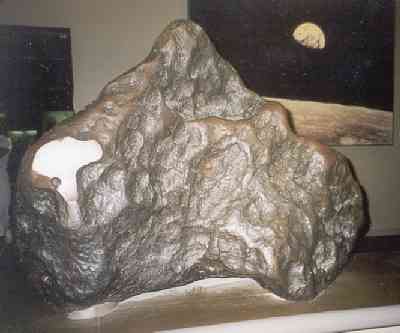

The Eskimos in Greenland,

matter of fact, made their iron tools for hundred of years from a large (30 tons) meteorite. |

|

Some American explorer (Admiral

R. Peary) finally stole it (he wouldn't have expressed it that way, though) in the 1890s and had a

hard time to transport it to the Natural History Museum in New York. Here it is: |

| |

|

We may safely assume that the old materials scientists tried

everything to smelt iron from suitable stones. They did have tricks to raise the temperature of a fire - in a 4500

old mastaba in Egypt, I took a picture of a relief showing six gold smiths

(probably rather their Ph.D. students) blowing into the fire with hollow reeds. But just blowing with lung power

will not do the trick for iron - maybe you get 1200 oC, but that's it. |

|

|

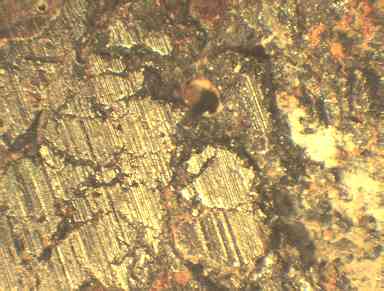

So in a typical fire with temperatures well beolw 1500 oC you

do not get liquid iron - but you do get solid iron

because reduction does take place - in a solid state reaction. What you get is an iron

bloom ("Eisenblüte" in German), a mixture of fine iron particles, unreacted iron

oxide, slag and charcoal residue. Here is an actual picture of some ancient bloom (from around 600 AD; I actually

"found" this myself (in some museum). |

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

The iron in the bloom was rather pure (and thus comparatively soft) because a

solid state reaction produces only iron - carbon or other impurities have to diffuse

in from the outside (if the iron would be liquid, it would just dissolve the dirt up to the solubility limit). |

|

The early iron smiths (probably being Hethites

of some form) could "wring" the iron from this bloom by separating the iron from the rest mechanically and repeatedly

hammering together what was left at high temperatures (about 800 oC; some of the slag then is liquid and

gets squeezed out) with, no doubt, proper prayers to the respective gods and many (magical) tricks. |

|

|

What they finally obtained was "wrought iron"

("Schmiedeeisen"), i.e. a lump of rather pure iron consisting of small pieces welded together, with plenty of

small inclusions (small, because of the hammering that breaks up large pieces of slag). |

|

|

Extreme care was necessary - from the selection of the iron ore, the reduction

process and the hammering business. If you were careless, the iron oxidized again (it really "burns" at temperatures

in excess of about 800 oC), and if you kept your reduction process going too long, carbon diffuses in

and you may end up with cast iron (C content about 3% - 4%; melting point as

low as 1130 0C). Then you actually got it liquid - "casting" was possible - but cast iron is

brittle and useless (for weapons, that is). |

|

|

Somewhat later, with larger furnaces and increased experience, the bloom obtained

may have contained some high-carbon melted parts on its top layer. It then consisted of a whole range of iron-carbon alloys

- from rather pure wrought iron to cast iron with good steel - say 0,5 % - 1,5%

carbon - in between. The art of the smith than included to pick the right pieces. This was a highly developed skill, we

know about it especially from Japan; but that

does not mean that the Kelts or others did not do it just as well. |

|

But beware. The art of making iron and steel, developed over 2000 years

in many civilizations, cannot be contained in a few lines, not to mention that very little is known about that story - iron,

after all, rusts (see the link showing an old sword), and not much has

been found that gives detailed knowledge about how the old romans, Indian, Chinese, etc. made their steel and iron products. |

|

|

Nevertheless - the early smiths, starting with the Greek god Hephaistos (the roman Volcanos) and containing

many fabulous figures like the Nordic "Wieland the

smith" or "Mime" in Wagners "Ring des Nibelungen", could produce articles, especially swords,

from the iron bloom that were much better than the customary bronze stuff (and than of course "Magical"

swords). In other words, they sometimes succeeded in making good steel. |

|

What was their secret? It is rather simple - looking at it retrospectively: You

need the proper concentration of C in the Fe bcc lattice at room temperature (some other impurities are helpful,

too; while others - especially S and P - were harmful). Raising the about 0,1% C in wrought iron to

an optimal 0,7 -0,9%, raised the hardness

(or better the yield point) threefold! But if you got too much - say 2% - you were on the road to brittle cast iron

not useful for swords. |

|

|

Not being able too melt iron (and thus not being able to throw some magical stuff

into the brew) the only way to get carbon (or on occasion N which also "works") into the Fe lattice

was diffusion via the surface. What you needed to do was to "roast" you iron (possibly the whole sword) for the

right time at the right temperature in a charcoal fire. Magic and praying helped - it did indeed: How do you keep track

of the time without a watch? You utter a long prayer that you learned from your master - the right ones "worked"!

The rest of the magical ritual was helpful in providing reproducible conditions. |

|

|

Of course the old practitioners had no idea of what the really were doing; if

they thought about it, they felt that were purifying the iron in the (more or less holy) fire. This erroneous believe (like

so many others) goes back to the (from a materials science point of view somewhat questionable) philosopher Aristoteles who certainly asked the right questions about life the universe and so on, and

is righteously famous for that. His answers, however, were invariably wrong - even in the few instances where he could have

known better. |

|

|

Well, we have made but the first step to steel. We now must make a few more steps

for good homogeneous steel - or we delve into a fascinating world of its own, the various damascene techniques, one of which is blending different kinds of steel into a compound material.

More to that in the link. |

|

Here we look first a bit on what happens in heating up and cooling down your material.

We know, after all, that going up in temperature, iron changes at 910 0C

from the bcc ferrite phase to the fcc

austenite phase. |

|

|

Carbon feels much more at home in austenite - its solubility

is higher than in ferrite. If the smith kept his iron in a good fire very long, he now might have had a rather carbon rich

austenite in the outer layers of his sword. So what happens upon cooling down? |

|

|

Well, it depends. If the iron cools down s l o w l y, the carbon rich austenite

will change to carbon rich ferrite. If there is more carbon in the austenite than the ferrite can dissolve, carbon will

precipitate, forming a new Fe - C phase called cementite (with a quite complicated

lattice). We now have cementite particles in fcc ferrite; usually in a very typical structure - both phases appear

like a stack of plates. This kind of structure is called perlite because, looking at it under

a microscope, it has a luster like pearls.. |

|

|

Perlite, the mixture of ferrite and cementite, however, is not much better than

bronze as far as its mechanical properties are concerned. So you must prevent the phase change from austenite to perlite

if you want to keep your sword "magic"! In other word, you must not allow enough time for the carbon atoms to

diffuse around during cooling as would be necessary for forming precipitates. In other words: You

must cool down rapidly (hopefully you did the proper exercise

for calculating how fast you must cool down). |

|

Here we have the next big trick - after making

bloom, extracting wrought iron, and carburization: Quenching - often the big secret of master

smiths (there is a whole Japanese mythology to this subject). The hot sword is stuck in a liquid for some time and thus

quenched - and only very unimaginative smiths would have taken common water at room temperature for that. |

|

|

If the cooling time was too short to allow Fe-C precipitate formation,

we now have a supersaturation of C in the ferrite phase which then will have a strongly disturbed lattice structure.

A kind of mixture between fcc and bcc phases will prevail which has its own name: "Martensite".

|

|

|

Now you did it: Martensite has the fivefold

"strength" of wrought iron! |

|

|

Unfortunately - if you got martensite at all, it tends to be brittle! Now the

next bag of tricks is needed: Heat up your sword again - but keep the temperature moderate.

|

|

|

Some of the defects that make martensite brittle

anneal out and its ductility goes up. Bang it (i.e. deform it plastically), and you produce dislocations

(hey, that's were we started from some time back!). Now you are manipulating a second kind of defect for optimizing mechanical

properties! |

|

|

But now we stop (so does the smith). If you really

want to know much more about this, use this link. |

|

|

Anyway, if everything worked, you now have a very good (and of course magical)

sword which was far superior to the bronze stuff of your opponents. In particular, you could make it longer

without having to worry that it might break in battle (which was about the worst health hazard imaginable then). |

|

And don't think that an increase in strength by a factor of 4 - 5 is not

all that much. The old Gauls, Asterix and Obelix notwithstanding, were conquered by the Romans not least because their swords bent

and needed straightening (over your knee) after a forceful blow - something the Roman swords did not need. (Haha - don't you believe all this Roman propaganda!) |

| |

|

|

Well, making a good steel sword was lots of work, lots of knowledge, and lots

of luck. Considering what could go wrong, it is quite remarkable that the old smiths actually did produce superior steel

swords now and then. Of course, probably more often then not, only the outer layer was steel, while the inside was still

soft wrought iron - the sword was made from compound materials, in fact. |

|

|

This gives us (and possibly also the old smithies) the idea of doing that from the start:

Weld together soft and hard layers, carefully picked from the bloom or made by carburization, and hope that the result will

combine the positive properties of both materials. We are talking damascene techniques

here. |

|

|

However, the word "damascene techniques"

is a collective identifier of several very different technologies. Most people associate it with a kind of compound technology

where two different kinds of steel were put together in layers and then forged into a sword or whatever. While this is something

that was done - especially by the Kelts and other North Europeans - it was not what the guys in Damascus did, the purported source of the famous damascene blades. |

|

|

As far as we know today, the "true" damascene technique actually worked with a famous

kind of steel, so called "wootz" which was produced in India for maybe a 1000 years in a kind of closely guarded monopoly. Wootz was rich in carbon (about

2%; there was a secret carburization technique) and the trick was to precipitate the surplus carbon in a pattern

of fine FeC3 precipitates. |

|

A fascinating world unfolds behind the catch word "damascene technique",

if you like you can browse the following links |

|

|

Damascene Technique in Metal Working |

|

|

Literature to Damascene (and Other) Techniques in the

Production of Iron and Steel From the Internet |

|

|

A Cross-Linked Glossary of Some Terms from the History

of Metal Working |

|

Steel technology was not confined to the Mediterranean and the European North

West. India may well have been at the apex of steel technology and China had its

own technology centered around cast iron, used not so much for warfare but for civil objects

like pots and pans. |

|

|

And lets not forget the Haya, a people who

lived in what is now Tanzania. They had a highly developed Fe technology

and used it for beautiful sculptures, too. Their myths and fairy tales contain many stories relating to the making of iron,

using a vocabulary that was heartily enriched with expressions relating to the making of humans. |

|

|

There is even some evidence

- collected recently (and, of course, being discussed

controversially), that the old Africans had the highest temperatures of all, even reaching the melting point of iron

some 2000 years ago (long before everybody else did) |

|

Whatever happened whenever and wherever, during the millennia, and despite the

many difficulties, iron and steel became common materials. At some time in the middle ages or Renaissance, the melting temperature

could be reached, but the mass production of good steel still had to wait for the 19th century. Before, only "thin"

objects - the paradigmatic "sword" or katana, scimitar, saif, shamshir, tachi, tulwar, yatagan,.. - could be made

by in-diffusion of carbon. |

|

Charcoal was replaced in the 17th century with coal, but not without unpleasant

surprises. Iron that was smelted with coal instead of charcoal was very brittle and completely useless. We now know, of

course, that minute amounts of sulfur in the Fe lattice - it segregates in grain boundaries - are sufficient to make

Fe brittle, and S, like other harmful impurities, is contained in regular coal in rather large concentrations. |

|

|

The solution to this problem, surprisingly, did not come from the military related strata

of society, but from the second most important enterprise dear to the hearts of men: beer brewing.

Brewers had tried to use coal instead of charcoal for roasting the barley - and produced a stinking abominable brew. Thusly

coke was invented: Roast coal in an environment deprived of oxygen - the stinky stuff will evaporate and what remains is

clean carbon - called coke - which could not only be used to brew beer, but was also usable for

the iron smelting industry. |

|

The beginning of the industrial revolution was severely hampered by the lack of

a large-scale process for the production of good steel. (Just imagine how the Si revolution would have fared without

large dislocation free and rather perfect Si crystals). The (at least in German and French) paradigmatic Eisenbahn (chemin de fer in French), the rail road, needs rails; with regular wrought iron

or cast iron the rails had to be renewed every 6 month because they deformed under the load (or cracked). Accidents

were frequent and often catastrophic. |

|

|

The production of large amounts of iron was common by then - the essential part was blowing

large amounts of air into the fire with the aid of mechanical bellows powered by steam engines. The leading British production

accounted for 2,5 million tons of iron in 1850, but the production of steel was still a cumbersome and expensive

business, accounting for a few percent of the total production. |

|

|

It was also known for sure since 1786 that steel had something to do with carbon; the

first person suspecting this was one Tobern Bergmann in 1774 (other sources, however, refer to Vandemonte, Berthollet and Monge from France). |

|

|

Still, all efforts to produce iron with the proper carbon content (and the right structure)

"from scratch", were in vain. Sometimes things worked, sometimes they didn't - there was no large-scale, reliable,

and reproducible process. And thus no big bridges, sky scrapers, safe railroads, big ships, efficient engines, and so on

- one rarely reflects how much cheap steel changed the world! |

|

This time, however, progress came from the military industrial complex. It became

simply too embarrassing that the big canons (made from cast iron) had a tendency to explode. Something had to happen. |

|

|

It was Henry Bessemer

who was especially interested in good steel for big canons, because he had just invented a new kind of projectile that received

some spin even from smooth bore guns (and thus was harder to destabilize during flight). Unfortunately, the canons couldn't

take the additional pressure building up while the projectile was building up spin as well as speed- they exploded more

than ever. So Bessemer was looking for large amounts of cheap steel. |

|

|

He was then the first person (so it was believed for a while) who had the genius idea of making

steel by getting carbon out of cheap, carbon rich cast iron,

instead of using the cumbersome way of getting carbon into low-carbon wrought iron.

The way to "drive out" the surplus carbon was to blast large amount of oxygen

through the cast iron melt (which, by the way, definitely needed the steam

engine; quite hard to do this through a reed). CO will form in the melt

which not only burns off to CO2 upon hitting the air, but by doing this supplies the heat to increase

the temperature of the melt because the melting point will go up with decreasing carbon content. If you stop at the right

time (looking at the color of the flame), you will be able to adjust the carbon content of a large amount of iron to just

the right value and thus produce large amounts of good steel. |

|

Mr. Bessemer, who was not exactly unknown before (he already had some fame as

the inventor of the "lead" pencil (which in reality contains graphite), after publishing his finding on Aug. 12th,

1856 became very famous - and very rich - quickly; everybody wanted his process. The London Times went as far as printing

the whole paper two days later. |

|

|

But point defects were fighting back. The industrial realization

of the Bessemer process with large quantities of ore and coke yielded a big and very

unpleasant surprise: Bessemer steel from large size production, in contrast to the Bessemer

steel from "laboratory" experiments, was brittle and not fit for anything. Bessemer felt like "being hit

by a flash of lightning from the blue sky"; the descend from the Olympic heights of top inventors to desperation was

quick and brutal. |

|

|

But Bessemer was a good materials scientist and engineer; if it worked once, it must work

again. There must be reasons for what happened, and with diligence, one can find out what is going wrong. What had happened? |

|

Well, Bessemers work, and the work of many others, supplied the (here much simplified)

answer. Bessemer used Swedish iron ore for his experiments (you always use the best

in lab experiments), while his industrial country fellows used English ore - and this

stuff contained some phosphorous. The Bessemer process (possibly in contrast to the old-fashioned steel making process)

did not remove the phosphorous, and small amounts of P are sufficient to render steel brittle. As we know now, P

segregates in the grain boundaries and changes the local properties in a detrimental way. |

|

|

Phosphorous had to be removed (if you lived in merry old England, out on a conquest to assemble

an empire, you did not want to have your steel production depend on the supply of Swedish iron ore). Two cousins, Sydney

Gilchrist Thomas and Percy Carlyle Gilchrist, found the way in 1875: Take (among other things)

chalk stone for the lining of the Bessemer

converter

and even add some to the melt. The phosphorus would react with the CaO of the burnt chalk and end up in the slag

which could be skinned from the liquid steel, or stuck to the lining. |

|

|

There were plenty of other problems - on occasion, e.g., some oxygen remained in the steel

and rendered it useless. Mr. Mushet, another Englishman coming

to the aid of his country, found the solution: Add some "Spiegeleisen" (an iron - manganese alloy found somewhere

in Germany) and your problems are gone. The Mn reacts with the surplus O and forms slag. It also neutrlizes

any sulfur in the mix, which would otherwise create real trouble. |

|

So besides Bessemer, many people were involved in bringing large scale steel production

to fruition. And, as it practically always will turn out with great inventions, somebody else did

it before. In this case it was one Mr. Kelly from the

USA, who had the "Bessemer" idea 10 years before Bessemer himself. While he made a mint over patent

hassles, the name Bessemer remains attached to steel, and Kelly is quite forgotten as a materials scientist. |

© H. Föll (Defects - Script)