| |

12.2.5 Sword Types and Static Properties |

| |

Comparison of "Ideal" Swords - Bending Within the Elastic Limit |

|

Let's perform a classical elastic bending

experiment with completely different kinds of swords that are, however, completely identical in their geometry.

Same blade length, same cross-section, same tapering etc. Let's look at the following list - Bronze sword

- Wrought iron sword

- Good ("eutectoid") steel sword

- Wootz steel sword

- Pattern welded sword

- Japanese type sword (katana)

|

|

Let's start by assuming that all those swords are made from homogeneous

and uniform materials, not containing any large defects or inclusions. In other words, we have perfect or ideal

swords from a material point of view.

|

| | |

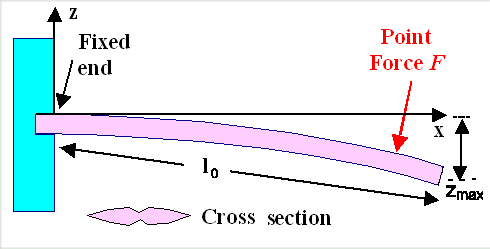

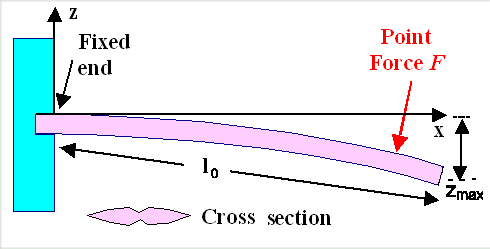

| | Basic geometry of the bending experiment

|

|

| |

|

We know that for a given force acting

on the blades as shown above once more, the amount of bending or maximum deflection

(given by the distance zmax) increases -

linearly with the magnitude of the force. Doubling

the force doubles the deflection

- with the third power of the length of the blade. Doubling

the length makes for 8-fold deflection

- inversely linearly on Young's modulus

Y. Doubling Y halves the deflection

- inversely linearly on the area momentum

IA that describes the cross-sectional geometry in just one number. Doubling IA

halves the deflection

Now let's bend these swords but within the elastic limit. That means that we use forces that are not large enough

to cause permanent changes in the blades. First we compare sword No 1 and No. 2: |

|

The only difference between these swords is Young's modulus. For wrought iron

and bronze we have

- YBronze=115 GPa

- Yw. I. =210 GPa

So wrought iron is considerably stiffer

than bronze; about 80 % to be precise, and thus will bend about 80 % less than the bronze sword.

|

|

You should now be a bit confused since neither bronze nor wrought iron are well-defined

materials. Do I mean 90% Cu / 10% Sn bronze? Arsenic bronze? Wrought iron with almost no carbon or with 0.2 % carbon? Those

are different materials after all. |

|

|

That is perfectly true. Nevertheless, Young's modulus for all those different

copper or iron alloys, summarily addressed as bronze or wrought iron, is about the same.

Differences are at most in the 10 % region and that is negligible for what we are doing here. I have emphasized

that before

and I have given the scientific

reasons for that. In essence, Young's modulus is a property resulting from the bonding between atoms and as long as

most atoms are of one kind, it is much the same. It doesn't depend much on what kinds of other atoms are mixed in as along

as there are only a few percent. |

|

Now let's include swords No. 3 - 6 in our comparison. They are made from very

different kinds of steel or from several kinds in some composite construction. Nevertheless,

their bending behavior in the experiment above is not noticeably different from the wrought steel sword. That's because

Young's modulus of all (low-alloyed) steels is about the same for the reasons given. The large majority of bonds is still

found between iron atoms.

However, in some of the steels we now may have a lot

of cementite, (iron carbide, Fe3C). Doesn't that make a difference? |

|

|

Yes, it does. Young's modulus of a composite material with large

percentages of other atoms will be some kind of average of the individual moduli of the constituents. I have shown you how

to calculate this.

Wootz steel for example, can be seen

as a composite of ferrite (=iron) and cementite (=iron carbide Fe3C). However, as it happens, Young's modulus

of cementite, around 200 GPa, is not much different from that of iron around 210 GPa. You don't have to believe

me, in reference 1 I give you one serious source plus the abstract of that paper. So no

matter how you average, you end up around the value of iron.

Of course, if you look closely you will find some differences.

But here we don't care about differences of 10 % or so. We simply commit to memory: |

| |

All iron / steel swords with identical

shape behave the same elastically.

Differences in elastic behavior of

iron / steel swords are always due

to differences in geometry

|

|

|

I know that this contradicts a large amount of what has been written about "elastic"

properties of composite swords. Pattern-welded swords are almost

always described as a combination of a hard but brittle steel with a soft but elastic one, giving you hard and elastic as

a result. Wrong on three counts:

- It's almost always a combination of a "regular" low carbon steel with a (somewhat harder, OK) phosphorous

steel.

- Why should the result be hard and elastic? Why not soft and brittle?

- The elastic properties do not depend on what kinds of steel you combine. They are the same for each steel and any combination

of steels you can conceive.

|

|

|

Other common mistakes often found in the literature are:

- Considering that "elastic" means "not being brittle" or in other words, confusing elastic deformation

with plastic deformation.

- Confusing yield stress (or fracture toughness) with elasticity. A steel with a high yield stress (=hard steel) is seen

as "more elastic" than a "soft" steel!

|

|

|

A sword might be pronounced to be more elastic for example if you can bend it to a larger

degree than some other sword before something unpleasant happens.

That leads us to the second point we want to look

at here: How do those still ideal swords compare if

I increase the force in the bending experiment to a value where "something" happens? |

| |

|

| |

Comparison of "Ideal" Swords - Bending Beyond the Elastic Limit |

|

So what happens if you bend until something

happens? What will happen? For the first three swords the answer is simple. All of them are ductile and therefore all of

them will deform plastically as soon as their yield stress is reached. This will first take place in the outer layers as

described before as soon as a critical force

is reached on the bending experiment. Then the stress in the outer layers exceeds the

yield stress of the material. It is not too difficult to calculate the stress in a bending experiment from the force but

it is no longer straight-forward as in a tensile test experiment.

If you keep increasing the force beyond the critical

level, the plastic deformation spreads into the interior because deeper and deeper parts experience the yield stress. In

the "neutral line (or plane) in the center, the stress is (ideally) always zero.

Since yield stress is (more or

less) just another word for hardness,

and hardness depends not just on the chemical nature of the material but also very much on its internal structure, only

general statements about the behavior of our swords can be made. |

| |

|

The first general statement is easy: As soon as parts of your blade deformed plastically,

it will not "snap back" to being perfectly straight after you release the force. The permanent bending effect,

however, may be small for reasons considered below.

Bearing this in mind, we now look cursorily at our examples form

above: |

| |

- Bronze is comparable in hardness

to wrought iron or even mild steel. So there shouldn't be much of difference between a bronze sword and one made from wrought

iron with respect to the critical force. However, since Young's modulus of the bronze sword is smaller than that of the

iron sword, it will have curved considerably more than the iron sword before it starts yielding plastically.

- Sword No. 3 was made from eutectoid steel, i.e. very good steel. Depending on its processing it could be harder than

a bronze sword and thus could resist larger forces before plastic deformation commences. You might be able to bend it into a semicircle before "something happens", i.e. plastic deformation.

- The behavior of No. 4, the wootz steel sword, is not easy to predict. It should be considerably harder than a bronze

sword and thus able to take a lot of force before plastic deformation starts, just like No 3. But it also could be brittle

and fracture right away at some not-so-well defined stress.

- Pattern-welded swords as No. 5 come in many types; they are all of the composite type. If you see a pattern, there are

at least two kinds of steel on the outside and the one with the lower yield stress will give first. You may not notice that,

however, if the other one is rather hard, and mistake its behavior as still being fully elastic when in fact it isn't. have

I have covered that before. We also may experience that "something else" happens: delamination in parts of the welds. In what follows I will look into the

behavior of composite swords a bit more closely since this is important for what follows

- There is of course no straight double-edged katana. But we can imagine such a composite sword with a soft core and a

hard outer shell like a katana; up to a point it is what's called a Viking

sword. As long as the hard outer shell gives first, everything is about the same as with No 3 or 4, except that permanent

bending progresses more quickly when the plastic deformation zone reaches the soft core.

It gets more interesting,

however, when the soft core starts to deform plastically before the hard outer shell. Think about that yourself for a while,

I will get to it later. |

|

In the case of swords No. 4 and 5 we are looking at properties of composite swords.

They are by definition "inhomogeneous" if still ideal swords. In other word, we have a composite of at least two

steels with quite different behaves concerning plastic deformation and fracture, even

so they have the same Young's module and thus behave identical as long as only elastic deformation

is concerned. But each steel of the composite construction is still perfectly homogeneous as we assume here.

|

|

|

We can't avoid any more to look a bit more closely on how an (ideal!) composite

material performs in a classic tensile test or bending experiment. I will do that in the next subchapter. |

| |

| |

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)