|

Composite Materials |

| |

Some General Blah Blah |

|

I gave you the basics about composite (or compound) materials way back, you better look it up before reading on. |

|

|

Here you have an advanced module, so gird

you loins (or have a beer or two). What I'm going to do is to calculate one property

of a composite material: its Young's modulus.

Before I do that, I give you some more general stuff about composite or compound materials. |

|

Let's start with a little disclaimer. Most Materials Scientists and Engineers

would not count steel among the composite materials proper

because it is not made by joining pieces of cementite and ferrite in some technical

procedure. It kind of makes itself by phase transformations from the homogeneous austenite.

However, this is only a

book-keeping point. If we look at properties, there is no reason not to consider steel to be a composite material. |

|

|

Next, we need to be aware of a crucial definition. When a chemist

reacts iron (Fe) and carbon (C) to iron carbide (Fe3C), she gets a chemical compound that has a name: cementite. She has not

made a composite material, she has just made a chemical compound. There is no way to calculate the properties of a

chemical compound from the properties of the elements it is made from. Think of water (H2O), for example, and

you get the point. |

|

|

The difference between chemical compounds and composite materials becomes even clearer with

a quick look at some "acknowledged" composite materials:

- Concrete, a composite material made from "stones" and cement (like Portland cement, consisting mostly of CaO

and SiO2).

- Iron reinforced concrete, a composite consisting of composite materials: it's made from concrete and iron / steel.

- Glass fibre reinforced polymer (GFRP)

- Carbon-fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP)

- You. Hard bones, soft brain, beer belly, ....

- Just look it up

|

|

|

That's what Materials Engineering

considers to be composite materials. In Materials Science, we cut a wider swath

(I always wanted to use that expression), as you shall see in what follows. |

| | |

|

| |

Young's Modulus of Ideal Fiber Composite Materials |

|

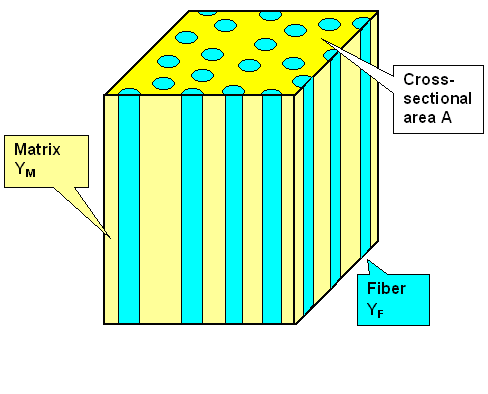

Let's calculate Young's modulus for some well-defined fiber-reinforced composite

(FRC) material. The fibers could be glass or carbon; they are embedded in a matrix,

typically a polymer like "epoxy". |

|

|

We assume (as is common) that the fibers have a large Young's modulus Y

or a large stiffness (not hardness!).

The matrix has a small stiffness. We also assume, for the sake of simplicity, that all fibers run parallel to each other.

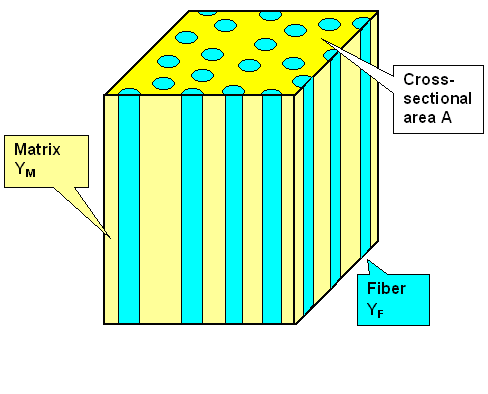

Our composite material then looks like this: |

| | |

| |

|

| Idealized fiber-reinforced composite material |

|

| |

| |

|

Young's modulus of the fibers we call YF. The matrix

goes with YM

, and we have YF > YM. The total cross-sectional area of the fibers in

a cut perpendicular to the fiber direction is AF, relative to the total area A. |

|

|

This means that the relative volume VF occupied by the fibers is

given by VF = AF/A

. This can be seen as is a kind of concentration of A (= fiber) in B (= matrix) |

|

Now let's do two tensile tests:

- We pull in the direction to the fibers or parallel.

- We pull at right angles to the fibers or perpendicular.

|

|

|

In both cases we assume that the bond between fibers and matrix is so good that

we do not just "pull out" the fibers. For a good composite material this is usually the case but that doesn't

mean that it is easy to achieve. |

|

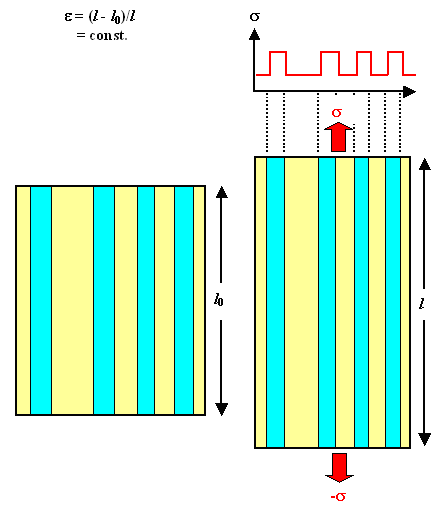

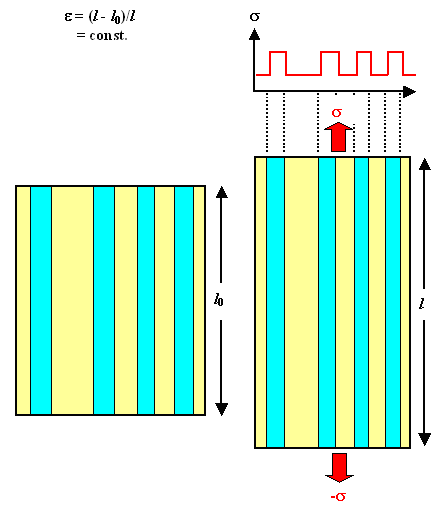

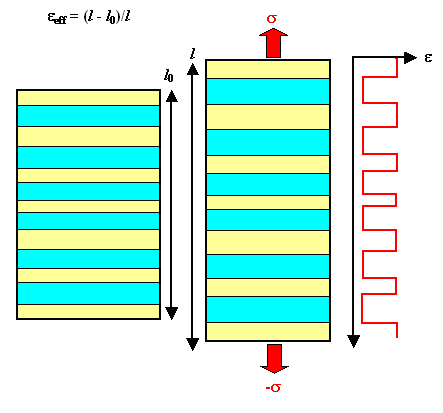

Let's start with the first case: pulling in fiber direction. The essential condition

is that we have the same strain

e

everywhere. This automatically requires that the stress

s must be different in fiber and matrix as shown in this figure: |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Conditions for tensile stress in fiber direction |

|

| |

| |

|

Now we can write down some easy equations: |

| |

| |

| |

|

| eCo= e =

|

eF= eM |

|

s F = |

YF · e |

|

sM = |

Ym · e |

|

|

| |

| |

|

Next, we take a little detour and calculate the total force

F that must act on the cross-sectional area A to produce the strain e.

For that we must sum up the total force acting on the fibers and the total force acting on the matrix. Since force is stress

times area, we have |

| |

| |

| |

| F = |

sF · AF |

+ sM · (A – AF) |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Even so the local stresses on the area A are different, we now

define an effective stress sCo acting on the composite material that is simply

given by the total force F divided by the area A: |

| |

|

|

|

| sCo = |

sF · AF

A | + sM ·

| A – AF

A |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Considering that sF,M = e

· YF,M, and AF/A = VF, we obtain |

| |

|

|

|

|

sCo = e · |

æ

è |

YF · VF + YM · (1 –

VF | ö

ø |

|

|

| | |

|

| |

|

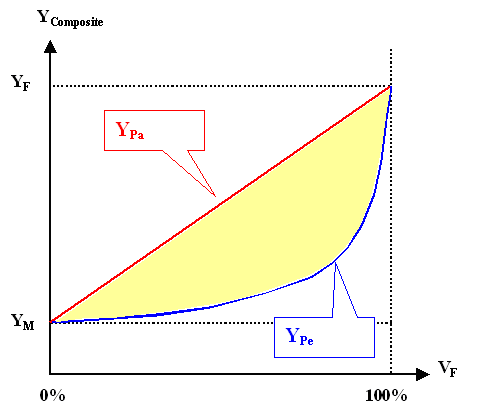

The expression inside the brackets is, of course, the effective

Young's modulus Y

Pa of the composite material parallel

to the fibers since it relates stress and strain. Our final result thus is |

| | |

|

| |

|

YPa(Composite) = YF · VF + YM · (1

– VF)

|

|

| | |

|

|

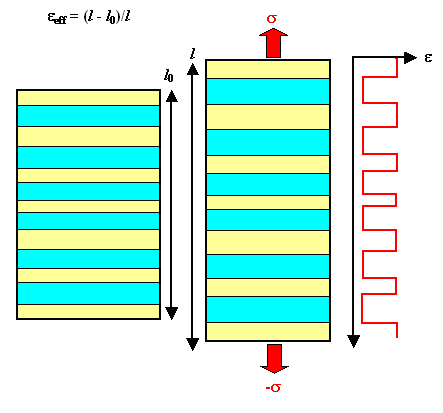

Now let's do the same exercise for tensile stress applied perpendicular

to the fiber direction. |

|

| |

| |

|

| Conditions for tensile stress perpendicular to the fiber direction |

|

| |

| |

|

I won't run you through the (rather trivial) math once more but just give you

the starting equations and the result for the effective Young's modulus YPe perpendicular to the

fibers: |

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

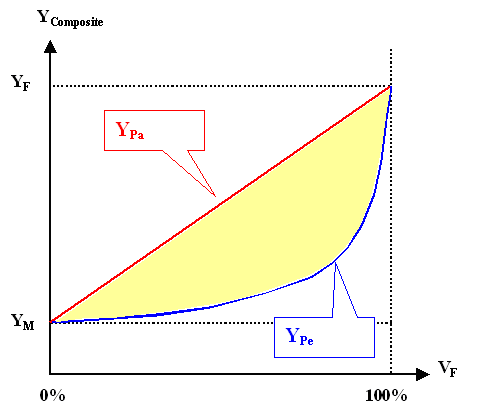

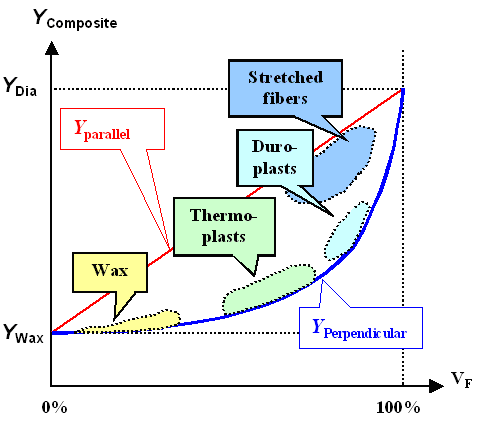

That is all rather simple and straight forward since we treated an idealized composite

material. The big trick comes now. As a first step we plot the results from above like this: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| Young's modulus for fiber composites as a function of the fiber "concentration"

|

|

| | |

|

|

Surprise!!! In the figure I have hidden Young's modulus for all

composites that consist of two materials with different Young's moduli! Can you see it? No? That's OK - neither could I

the first time I run across this. |

|

|

In a general way of speaking, Young's modulus of the compound materials is some

kind of average of the moduli of the constituents. Not a simple average, mind you, but something in between the two individual

values. There is no way that Young's modulus of a composite can be much large or much smaller than the respective individual

values. This general statement also applies to most other properties and is sometime known as "the law of averages" (for composites) |

| | |

|

| |

Young's Modulus

(and Other Properties) of Any Composite Material |

|

The point is: The two cases I have treated are the extreme

cases. No distribution of some material A with a large Young's modulus inside

a material B with a small Young's modulus can have a larger effective composite Young's modulus than the "parallel

fiber" case. Neither could it be smaller than the perpendicular fiber case. |

|

|

Any arrangement of A inside B

with a given volume fraction of A has a Young's modulus that is somewhere inside the yellow area in the figure above.

A could be fibers randomly distributed with all kinds of lengths, round pebbles, whatever.

You can even make

an educated guess if Young's modulus is closer to the lower or upper border, depending on how A is arranged inside

B. |

|

|

Of course, if you want to know it precisely

, you have to go through rather complex calculations. But whatever you get in the end will be inside the yellow area

for sure. |

|

Knowing this, we can predict Young's modulus with some confidence for quite a

few composite materials. I give you one example. It is a bit off the ordinary way of thinking about composite materials

but quite revealing: All polymers can be considered to be composite

materials! |

|

|

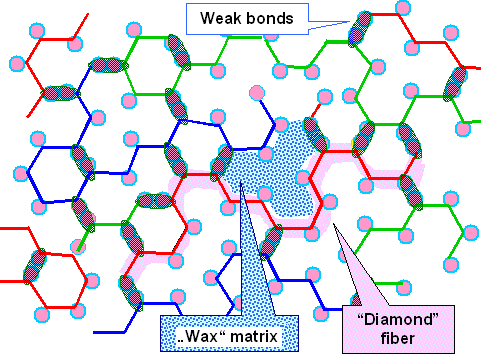

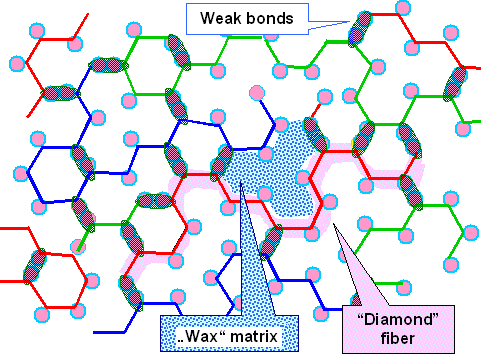

A polymer is a material that consists of long chains of carbon atoms, linked by strong bonds

like in diamond. We can therefore assign a Young's

modulus to these chains that is similar to that of diamond. The carbon atoms of the chain or fiber

are also bonded to atoms or molecules that connect the chains by weak bonds. The stuff between the "diamond-like"

carbon fibers thus can be considered to be similar to a material that is "weak"

- let's say wax. This is schematically shown below. |

| | |

|

|

|

| Diamond-like ...-C-C-C-... chains in a wax-like matrix |

|

| |

|

| |

|

Bingo! As far as Young's modulus is concerned, any polymer is now a composite of diamond-like

fibers and a wax-like matrix. The difference between different polymers is due to different volumes of the in-between (large

molecules bonded to the carbon atoms take up more room than the small hydrogen atoms in the most simple case of polyethylene),

and the arrangement of the fibers (random distribution like a tangle of spaghetti or ordered and parallel). |

|

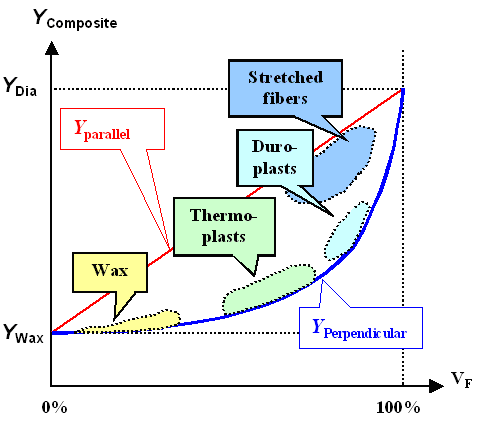

This is what you get if you compare calculations and reality: |

| |

|

| |

|

Young's modulus of polymers. Model and reality

If that isn't convincing, what is? |

| Source: While this is more or less common knowledge, the figure is based on

the wonderful book of Ashby and Jones |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Thermoplasts are the (softish) polymers that get soft and more or less liquid when heated

a little. Your plastic shopping bag, CD's, plastic containers, etc. are made from thermoplasts. Duroplasts will not get

soft upon heating but begin to smolder and stink. Epoxy is an example. Stretched fibers is what you use to tie your ship

to the quai. |

|

Time to generalize. As you have seen, it is not too difficult to get a good idea

for one particular property - Young's modulus - of a composite material if you know the respective properties of its constituents.

It is also not to difficult too get an idea about some other properties in this way

- always provided that you can do some averaging. Examples are: - Density (rather trivial)

- Electrical conductivity (as long as all constituents are conductors)

- Index of refraction (as long as all constituents are transparent and much smaller than the wavelength of the light)

- Magnetic behavior (as long ... you don't want to know this)

|

|

|

However, you are going to run into limits rather quickly, too. The method only works as long

as you have "linear" relations, and that is quite often not the case. For example, it is not easily possible to

calculate: - Plastic deformation and fracture

- Electrical conductivity if one constituent is an isolator.

- Index of refraction if the (transparent) constituents have dimension in the order of the wave length.

|

|

Now let's look at a composite sword made

from "hard" and "soft" steel. What are the properties? Let's look at a short list:

- Young's modulus. Since both steels have the same

Young's modulus, our composite sword has simply Young's modulus of steel.

- Yield strength . There is no such thing as a composite yield strength. Each component

yields as soon as its individual yield strength is reached. In a composite sword, the soft component thus will deform plastically

long before the hard component; we have elastic and plastic deformation in parallel. This, however, may not be obvious to

the user because the elastically stressed hard component will pull the sword more or less back into its original shape as

soon as the external stress is released.

- Fracture Toughness. As above. In this case the hard (and thus more brittle) part

might break locally long before the soft part. This, however, may not be obvious to the user because the soft components

will still hold everything together.

|

|

|

Now you have a lot of very concentrated food for thought. I will come back to these topics

in detail later. |

| |

| |

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)