Iron in China

Otherwise it is always a good idea to consult the work of Donald B. Wagner, e.g. his book "Iron and steel in ancient China" (Leiden: Brill, 1993), and what Vincent E. Pigott has to say about that book. 3)

Many articles on ancient Chinese metallurgy appear to be heavily biased towards "China was always ahead by definition", and I have a problem with this kind of view. Here are some random examples from the Internet:

| During the Spring & Autumn Period of the Warring States Period, China invented many superior casting processes like the wrought iron technique, crude iron technique, wrought steel technique, cast iron technique, cast iron for decarburized steel technique, tempering technique and standardized iron casting technique." |

| "Iron was smelted in China by the 4th century BC, and steel was perfected

by the 400's AD using coal as a high temperature fuel. By having good refractory clays for the construction of blast furnace

walls, and the discovery of how to reduce the temperature at which iron melts by using phosphorus,

the Chinese were able cast iron into ornamental and functional shapes." "As early as the Fourth Century A.D., coal was used in China, in place of charcoal, as fuel to heat iron to rework the raw iron into finished products. Although sources on the use of coal in the Song Dynasty (960-1279 A.D.) are limited, the Chinese are reported to have developed the ability to use coal in the smelting of iron by the Ninth Century. The use of wood to make charcoal was causing deforestation". |

| "The Chinese probably discovered copper-smelting and bronze-making independently of the West, because their pottery kilns were much superior." | |

| No, they didn't. It is far more likely that copper and bronze technology diffused in from the West. | |

| "However, their advanced technologies of melting and casting made it unlikely that they would independently discover iron-working, because the technology of forging iron to purify the bloom was not part of their way of operating." | |

| Huh? Because they are so advanced they cannot discover a simple technology? | |

| "Sometime after 1000 BC, knowledge of iron-forging techniques reached China from the West. The Chinese then applied their superior furnace technology to take iron-working to new levels of expertise. They were the first to cast iron into useful objects, because they could routinely melt iron on a large scale." | |

| No. They did not cast iron into useful objects, they cast cast-iron into some useful objects but missed out on many other useful objects that needed to be made from wrought iron or steel |

| "About 300 - 400 BC, the Chinese learned that if a cast iron object is reheated to 800° or 900° in air, it is decarburized, that is, it essentially has some of the carbon burned out of the surface layer". | |

| They certainly did not learn that. They had no idea about elements. They just learend that product properties improve somewhat by this process. | |

| "This process forms a skin of lower-carbon iron (steel) over the

cast iron core. The finished tool is hard and wear-resistant, and for most uses is comparable with the end product of Western

forging, in which a skin of steel is formed over a core of wrought iron by forging." | |

| Complete and utter bull shit. A brittle material coated by a few micrometers of tough steel is still a brittle material, Coating your glass sword with some Scotch tape will no really make it much better. | |

| "But the Chinese technology was far more efficient. The Chinese cast objects already had the precise shape required, whereas Western smiths had to produce the right shape by hammering wrought iron on a forge. The Chinese could effectively mass-produce cast steel-jacketed tools of all kinds, while Western smiths had to make them one at a time". | |

| True. The stupid Western method had one slight advantage, however. Their products were often far superior! |

| "The Chinese were building cast iron suspension bridges from the 6th century, 1200 years before the Europeans." | |

| Maybe. I haven't seen it beause it is not around anymore. The Hagia Sophia or the Pantheon, however, considerably more complex than a suspension bridge and built a bit earlier by the Europeans, is still around. |

| |

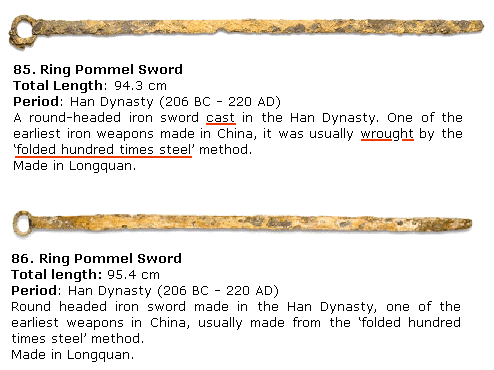

| "Early" Chinese Swords | |

| Source: Macao Museum of Arts; History of Steel in Eastern Asia |

I'm not saying that China isn't a very old culture that was superior to others in some aspects of civilization and technology some of the time. Be that as it may, as far as metal technologies in general, and iron technology in particular was concerned, they weren't all-out superior, they just were very different.

The art of making metals including iron actually arrived (or was discovered) rather late in China. That is also true for copper and bronze, but in particular for iron. After iron smelting was started, however, it developed very quickly and in a peculiar way. The Chinese, it appears, made almost exclusively cast iron in what one would call a blast furnace nowadays, essentially skipping the making of wrought iron in "bloomeries".

Steel was made by "fining", i.e. taking the carbon out of the cast iron by burning it off in air. That is the principle of steel-making today. The early Chinese techniques included a kind of puddling" process, which is similar to processes used in the West much later (let's say after 1500 AD). Does that mean that the Chinese were 1000 years or so ahead of the West? It's a matter if definition. If you prefer a bad steel made by an advanced method to good steel made in an old-fashioned way, the Chinese were ahead.

But only 1 forge? That indicates that the vast majority of the cast iron produced was indeed cast into molds for making tools (like digging implements), pots and anything else that can be made from brittle cast iron. Don't make the mistake of conisdering brittle = weak, useless, not strong. Your toilet is made from brittle material but easily takes your weight and other abuse for long times.

Steel making by "fining" or "puddling" the cast iron, followed by forging the steel, was not only a laborious process but could not have produced high-grade steel easily.

The Chinese, to their everlasting credit, used their cast iron for making peaceful objects, including flower vases and (huge) sculptures. Western cast iron, when it was finally produced, went immediately into cannon making. So the Chinese certainly take the price for being the good guys. Our ancestors were the bad guys by comparison. That might be morally questionable but has its advantages. They easily conquered and subdued the good guys with their superior iron / steel weapons. Look up what the British did in the so-called "opium wars". Of course, nowadays they are really sorry for that, and acknowledge that the Chinese had the moral superiority then. (Haha, good joke, huh?). Some of our German (good) guys around this time wrote the music that the Chinese (and everybody else on this planet) like to listen to ever since, by the way.

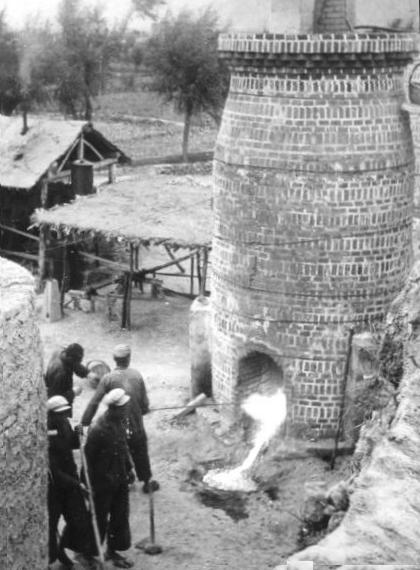

While the Chinese cast-iron industry was far ahead of the rest of the world around 200 BC, there is also another side to this: The technology hardly changed during the next 2 000 years or so. Here are pictures from smelting cast iron and "puddling" steel from 1958:

|

|

| Tapping of a blast furnace in Wushan, Gansu, 1958 |

|

|

| Puddling steel around 1958 "Operation of a traditional type of fining hearth in Shanxi" | |

| Source: Alley, Rewi 1961b "Together they learnt how to make iron and steel. Some early types of furnaces used in 1958-9, in China". Collection of the Needham Research Institute, Cambridge. |

|

|

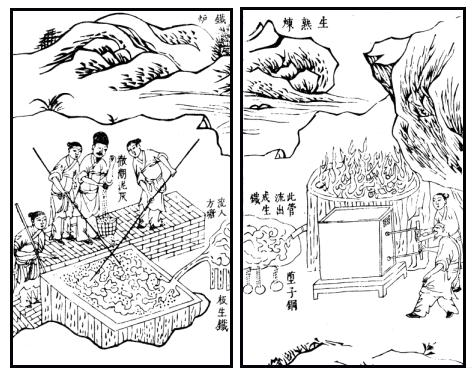

| Making cast iron (right) and puddling steel (left) in the old times | |

| Source: "Furnaces for refining cast and wrought iron", illustration in Tian gong kai wu (reproduced from 1637 ed). All over the Net |

"The description and illustration are so precise that there is no real doubt that Song Yingxing, or the author of his source, had seen something very like this process. But it is very difficult to explain. Anyone who has worked with molten cast iron, as I have, will immediately object that the cast iron from the blast furnace, flowing into such a large open hearth, without thermal insulation, fuel, or any sort of air blast, will solidify before any significant amount of carbon has been removed.

Most translators and commentators seem unaware of this objection. They explain the passage and illustration in terms of modern open-hearth steelmaking processes, and state that the curious "wuchaoni" (some sort of earth used in the process) would contain iron oxide, FeO, to help remove carbon by the reaction FeO + C = Fe + CO, but this would not solve the problem.

The only commentator, as far as I know, who has been aware of the problem was one of the first, the German metallurgist Adolph Ledebur, more than a century ago, and he also proposed a solution. A Japanese friend had shown him a copy of Tian gong kai wu and translated the metallurgical sections for him. In his article about it he suggests that the wuchaoni spread on the iron contained saltpetre (potassium nitrate, KNO3). It is a powerful oxidizing agent (this is its function in gunpowder), and might very well be able to accelerate the oxidization of the carbon in the iron sufficiently to keep the temperature up until the carbon is exhausted and the cast iron has been converted to wrought iron."