|

Fracture Mechanics II |

| |

Flashback and new Goals |

|

If you have read through the backbone of this chapter, you are now a better person

because you know something about plastic deformation, dislocations, and all the other defects making crystals more colorful

in both meanings of the word. That's good because now I can continue the "Fracture Mechanics" stuff I have started

when you were an ignorant....(insert you job title or whatever else is right).

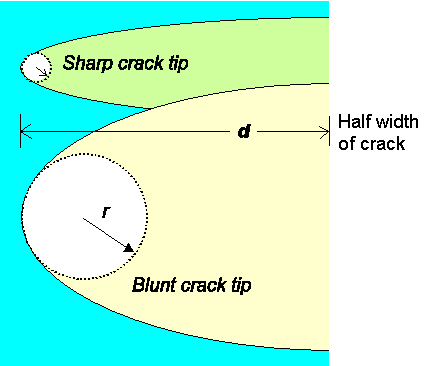

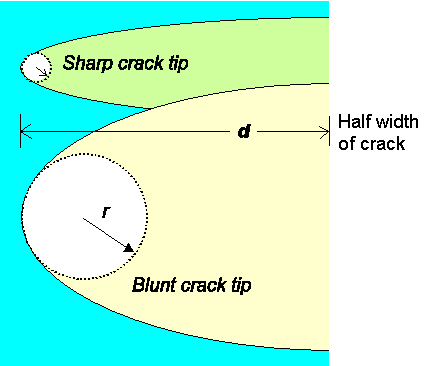

Let's quickly review the essentials of

the first Fracture Mechanics module. The figure below illustrates

the basic ideas: |

|

| |

| | |

|

| Geometry of microcracks and fracture mechanics. |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The basic points to recall are:

- The rapid growth of pre-existing small "microcracks", characterized by

their half-width d and tip radius r, leads to fracture in brittle

materials.

- On a macroscopic level, the fracture criterion ("Griffith criterion")

can be derived from an energy consideration. Fracture in uniaxially strained materials occurs at some critical stress scrit if more strain energy is released than surface energy generated. The

basic equation for this was (with Y = Young's modulus, g = specific surface

energy):

|

|

|

| scrit |

= |

æ

ç

è |

2Y · g

pd |

ö

÷

ø |

1/2 |

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

- The criterion is purely energetical and does not take into account the crack tip

geometry and the stress concentration there.

- The criterion is only applicable to perfectly brittle materials under uniaxial stress with cracks oriented perpendicular to the stress direction.

|

|

In other words: While Griffith's work was seminal in the sense that it produced

major insights into fracture science, it is rather limited and does not allow fracture

engineering. One of the reasons is that even for perfectly brittle materials, the surface

energy g is not really a good parameter. It is not all that well defined for real materials

that have never a clean surface but always a "dirty" one, covered with oxide and God knows what else.

We thus

need to modify the simple approach, considering in particular ductility and more complex stress situations than just uniaxal

deformation. |

| |

|

| |

Fracture and Ductility |

|

The first thing to do is to rewrite Griffith's criterion to make it more general.

We do that by defining two new parameters as follows: |

| | |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Formally, the new quantity "critical stress intensity factor" KIc

would be equal to (2Y · g)½. This factor relates to crack

growth by giving the energy needed via g, and the energy gained via Y. Let's

forget that now and accept that KIc somehow takes care of all

energies involved instead of just the surface energy g and simple strain energy.

Just

as Y and g are material "constants", somehow encoding a major

property of a given material, so is KIc. It's just no longer simply the product of the two old

parameters but something new that we measure since we cannot really calculate it very

well.

If we know the critical stress intensity factor of some material, we know at what (uniaxial) stress it will fracture

if it contains microcracks with half-width d. |

|

|

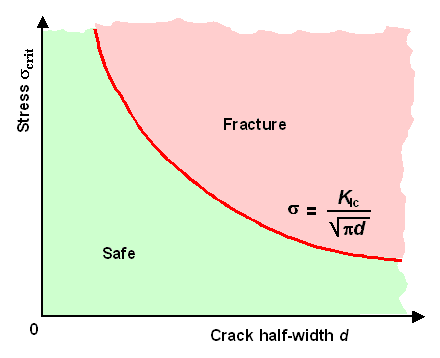

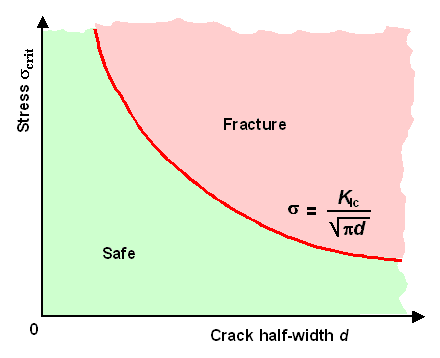

If we now plot the critical stress scrit versus

crack size d we get this curve: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| Brittle fracture with the stress intensity factor . |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The red line, described by the simple equation with the critical stress intensity factor or

fracture toughness KIc separates safe combinations of crack length and stress from combinations

where instantaneous fracture occurs. This is still nothing new but just the Griffith criterion expressed as graph. . |

|

So far I have just renamed things; there is not really something new. The new

inputs come now. They are:

- The curve separating save and deadly combinations of stress and crack size (the red curve above) can actually be measured in some special test. That's how we get numbers

for KIc

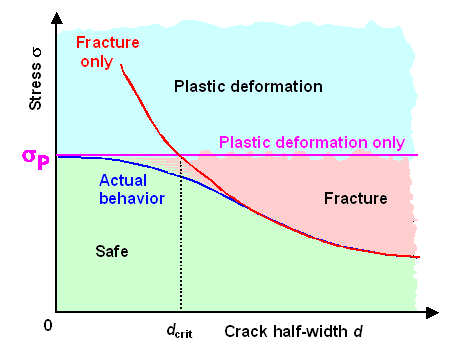

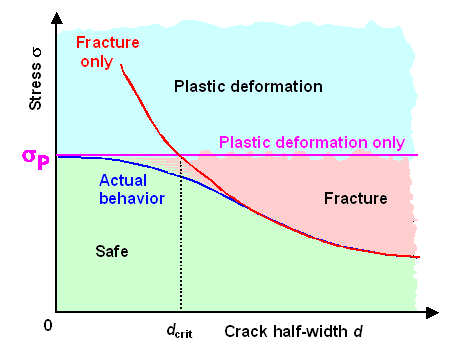

- So far, everything concerned only brittle materials. But we can take care of ductility now. All we have to do is to add a straight line at the specific yield stress

sp of the material to the figure above

What we get is this: |

|

| |

| |

| | Brittle fracture with the stress intensity factor . |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The red line, as before, separates separates safe combinations

of crack length and stress from combinations where instantaneous fracture would occur if there

would be no plastic deformation. The mauve line gives the yield stress sp; above it only plastic deformation will occur.

That means that nowhere in the material can be stresses higher than the yield stress; they would always be released because

dislocations form and move, and thus change the shape of the material in such a way that the stress is reduced.

If we

now measure at what kind of combinations of crack width and stress sudden fracture will

occur, we get the blue curve. As one would expect, it is a smooth change-over from brittle-like

fracture behavior to ductile behavior, where the specimen does not fracture under stress, but just "gets longer".

Of course, the transitions are not precise and sharp. I tried to do justice to that by using wobbly lines and mixed colors

at the boundaries. |

|

|

It is convenient to define a critical crack half-width dcrit

as shown, using the intersection point between the two curves for fracture only, or plastic deformation only. |

|

I guess you see the good news yourself: You don't have to worry anymore about

small microcracks! Sudden fracture does not occur at all

for stresses above the yield stress and cracks smaller than some critical crack half-width

dcrit. You will experience yielding before fracture.

That might not be great but still far better than the opposite. |

|

|

For cracks smaller than dcrit, plastic deformation will

take care of them. Since, as we learned before,

the stress around the crack tip is higher than the global or macroscopic stress, plastic deformation at the crack tip starts

long before the crystal deforms as a whole. This blunts the crack tip and reduces the stress to levels where the crack does

not propagate.

This is not a minor effect. The critical crack length might increase to huge values like millimeter!

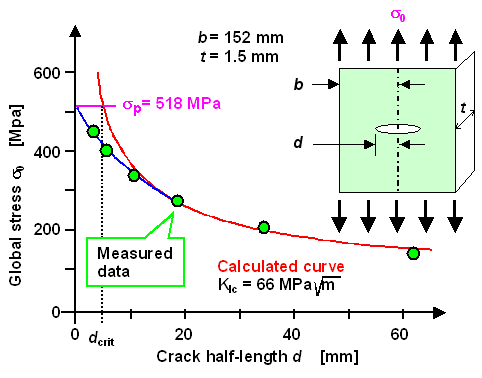

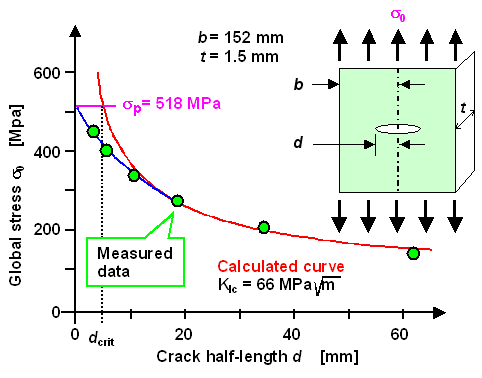

Here is a figure showing this with a real example: |

| |

| |

| |

|

| Data for cracking an aluminium alloy at –195 oC (–320 oF)

. |

| Source: Redrawn after T.W. Orange: "Fracture toughness of wide 2014-T6 aluminum

sheet at -320 oF", NASA TN D-4017, 1977. |

|

| | |

|

|

|

This kind of aluminum alloy can live with cracks as long as about 5

mm (!!!) without catastrophical fracturing or fracturing before yielding.

In other words: while you can never outsmart the first law of Materials Science, you much prefer that some pressure vessel, for

example, starts bulging and sort of getting bigger because it deforms plastically, before it finally cracks and explodes,

to sudden fracturing / explosions without any warning. Same thing for that steel girder. Slow bending because it elongates

plastically before it finally breaks, while not good, is still much preferable to sudden rupture. And so on. |

|

|

Measurements like the one above allow to extract values for KIc

and for the yield stress sp. Of course, we know sp

from independent tensile testing experiments already, so we even have a check if everything is as it should be. Here are

a few numbers: |

| | |

|

|

|

| Material | Fracture Toughness

KIc [MPam½] |

Yield Stress sp

[MPa] |

| Steel (AISI 1144) | 66 |

540 | Cr-Mo-V Steel

(ASTM A470-8)

| 60 | 620 |

High-strength Steel

(18-Ni maraging) | 123 |

1310 | | Al alloy (7075-T651) |

29 | 505 |

| Ti alloy (Ti-6A1-4V) | 66 |

925 |

Polymers

(Polyester, PVC, PET) |

» 0.5 - 5

0.6, 2.4, 5.0 |

- |

| Ceramics (Glass, concrete, "china" (Al2O3)) |

» 1 - 8

0.76, 1.19, 4.0 |

- |

| Source: N.E. Dowling: "Mechanical Behavior of Materials",

3rd edition 2007, Pearson / Prentice Hall |

|

| | |

|

|

|

With these numbers we can "somehow" calculate the blue curve and thus

the critical crack length dcrit. This means that we now have design criteria; we can start to construct

things that do not break. Fracture engineering starts here. |

|

Unfortunately, it doesn't end here. There is far more to making safe things that

do not fracture now or ever, provided my kids or my wife don't get to (ab)use it. Topics to consider, for example, are:

- Accounting for cases where the specimen dimensions are not far larger than the crack size (always assumed so far). This

leads to rather long equations and a lot of tricky approximations.

- Accounting for more complex geometries than just uniaxial stress. This leads to more fracture toughness numbers, labeled,

for example: KIIc and KIIIc; the "I" so far

always referred to simple uniaxial cases.

- Considering the precise stresses and stress distributions at the crack tip, and not just the approximations used so

far (that's where the "simple" K comes in). You definitely do not want to know about this.

- Calculating KIc instead of measuring it. Something to avoid at all costs.

- Considering rapid deformation, i.e. building up stresses faster than they can be relaxed by dislocation movements. Fun

to do experimentally (e.g. in sword fights or by exploding things), but very hard to calculate.

- Considering what could happen fracturewise as time progresses. Keywords are "creep"

and "fatigue".

- Going for "safe" design, allowing to make parts that do not fracture even if something goes wrong (your wife

uses your knife as a screw driver, your car hits a tree, your satellite is hit by a small meteorite, .... ).

|

|

|

If you want to know more about this, you need to apply yourself - for a few years.

There are no more easy fixes and shortcuts. Sorry. |

| |

| |

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)