| |

Early Places With Metals:

|

|

Asikli Höyük is similar to Çatal

Höyük but even earlier. It's occupational period was from 8200 BC – 7400 BC. We have rectangular mud-brick

buildings entered through the roof; plastered and occasionally painted walls, skeletons in the cupboard

excuse me - under the floor, and so on. |

|

|

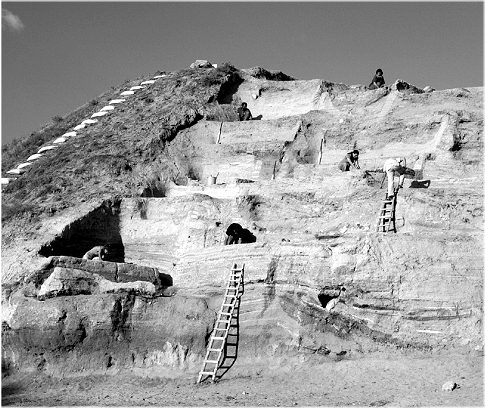

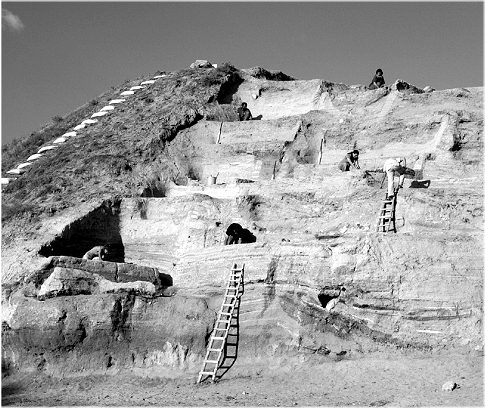

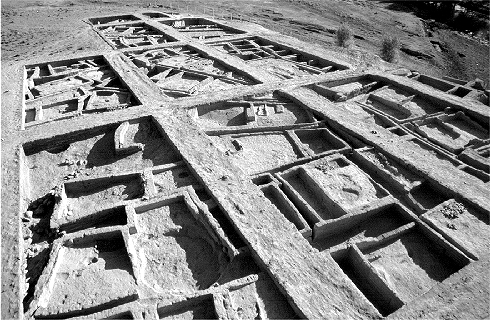

It's easy enough to imagine such a settlement; it's not so easy to actually dig

it up. Here is a picture of what digging in Asikli Höyük implies. |

| | |

|

|

|

| | Digging in Asikli Höyük |

| Source: Mihriban Özbasaran: "RE-STARTING AT ASIKLI" The Anatolia Antiqua XIX (2011), p. 27- 37

|

|

| | |

|

|

|

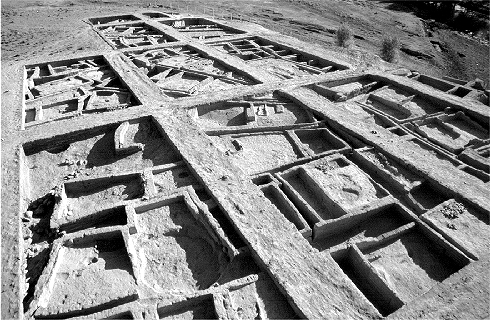

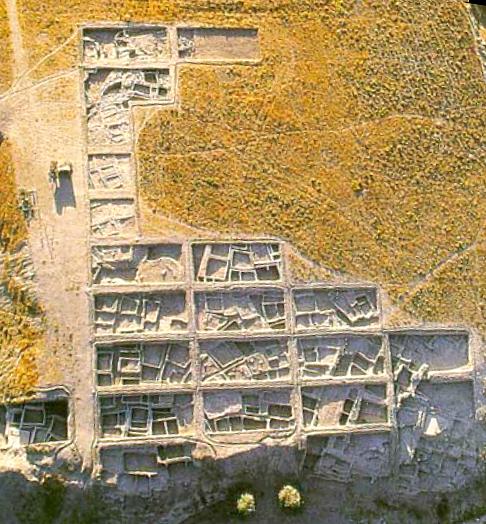

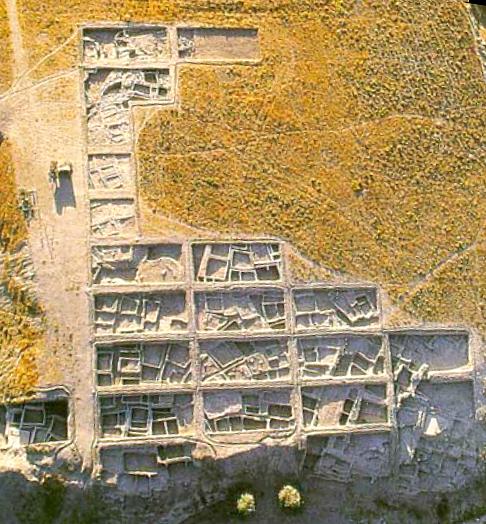

New buildings where continuously raised right on top of "collapsed"

old buildings, and all that's left in most places is a compact layer of stratified debris forming a mound.

What one

can see on a visit looks like this: |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| Asikli Höyük today |

| Source: Mihriban Özbasaran: "RE-STARTING AT ASIKLI" The Anatolia Antiqua

XIX (2011), p. 27- 37 and Hadi Özbal: "Ancient Anatolian Metallurgy". Internet presentation. With friendly

permission. |

|

| | |

|

|

Asikli Höyük, like Çatal

Höyük, may have "lived" from the obsidian trade. Plenty of the stuff was found there, and the artisans

of the place could do amazing things with this hard and brittle material (it is essentially like glass). The (parts of the)

obsidian bracelet shown below has been investigated in great detail1). As one

would have guessed, it took a lot of skill for making it with only primitive stone tools |

| | |

|

|

Obsidian bracelet (model) from Asikli Höyük

The left side shows a part

of the real thing | | Source: Internet at large |

|

| | |

|

The Asiklians left some burial gifts; a potpourri is shown below. It is of interest

for us because it is supposed to include copper things |

| | |

|

|

|

| | Burial gifts from Asikli Höyük |

| Source: Master Thesis of F. V Güngördü; who had it from Esin, U., Harmankaya,

S. 1999. “Asikli”; In Özdogan, M. and N. Basgelen, eds., "Neolithic in Turkey, The Cradle of Civilization,

New Discoveries". Ýstanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat. |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Well, I'm not sure if I see copper there. So let's look at the real stuff: |

| | |

|

|

|

| | Copper beads from Asikli Höyük |

| Source: Master Thesis of F. V Güngördü; who had it from Esin, U., Harmankaya,

S. 1999. “Asikli”; In Özdogan, M. and N. Basgelen, eds., "Neolithic in Turkey, The Cradle of Civilization,

New Discoveries". Ýstanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat. |

|

| | |

|

|

|

That's it. There are some more beads and other small parts, and some of them have been analyzed

in detail. They go back to the 8th millennium and were made from native copper, mostly by producing thin sheets by hammering,

followed by rolling into beads. The microstructure analysis indicates some annealing, so exposure to high temperatures after

the hammering (or in between) must have taken place.

Technically, annealing means that grain boundaries and dislocations

can move with some ease, which in turn means that atoms become mobile via vacancies; consult the diffusion

super module for details. Typically, this happens at temperatures around 2/3 of the melting temperature. For copper

(melting temperature 1084 oC; 1982 oF) temperatures around 600 oC (1112 oF),

easily reached in a regular fire, are thus sufficient. One might conclude: |

| | |

|

| |

|

For people who could make the objects shown above, the production of some copper beads should not have

been a problem.

|

|

| | |

|

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)