| |

Complex Patterns: Wood

Grain and Mosaic |

|

There is more that one can do with striped rods. Here is the next example: |

|

|

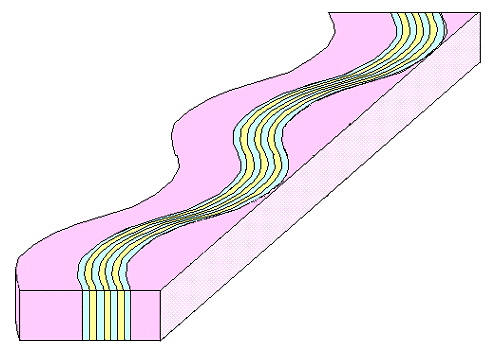

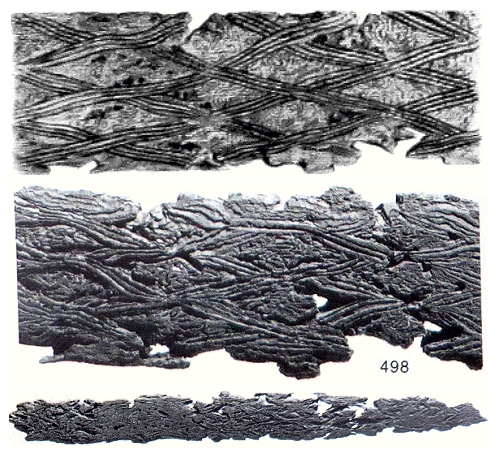

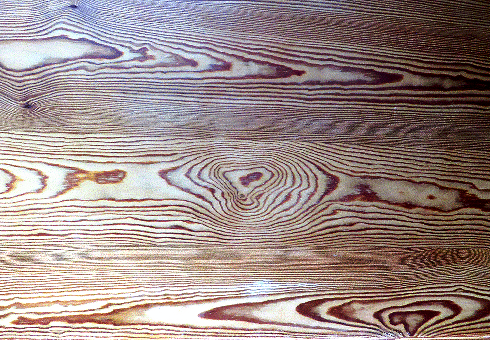

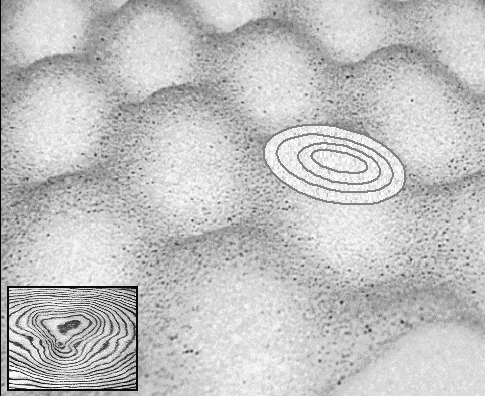

Make the stripe rod a bit bumpy or wavy. Cut through it at more shallow

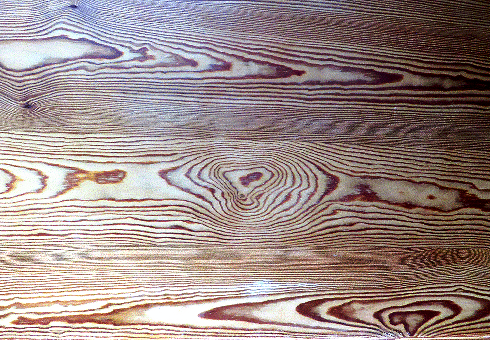

angles. Look at wood and you know what you can get. The following picture gives an example: |

| | |

| | Woodgrain |

|

|

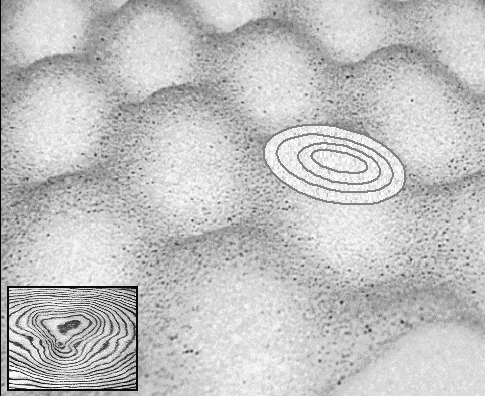

Now make your striped rod bumpy in a defined way.

Make little hills or bumps (bang it from behind with a ball-shaped hammer, arranging the bumps in a kind of grid) until

the surface looks kind of like an egg carton. Then grind it flat again. What you will get are more or less well-defined

systems of rings on one side: |

|

|

|

How to make mosaic patterns

A wood grain example in the lower left corner. |

|

|

|

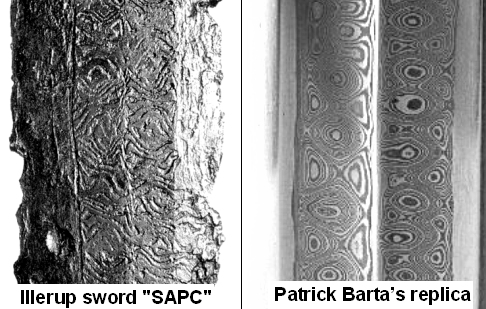

The "Illerup" sword shown is rather unique. It belongs

to what I have termed "Illerup swords with special patterns" and there are several special modules that go with

that: |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The "Link Hub" for Danish bog finds, the places where many pattern welded

swords were found |

The place where many swords with special patterns have been found, often extremely

well preserved |

Details about some swords from Illerup with special patterns |

The scientific classification of 12 sword types for the first 5 centuries AD. |

| |

|

|

Now let's look at pattern that cannot be made with striped rods. |

| |

|

| |

Complex Patterns: Palmette and Chevron |

|

Let's look at question No. 1: How to make complex patterns?

Some swords found in the Danish "bog treasures" and in other places

showed what is often called a chevron pattern, a palmette

pattern, and combinations of the two. There are many examples in the "Illerup

Swords with Special Patterns" module. But we also find them in the probably very first publication that addresses

pattern welded swords: Conrad Engelhadt's books

about the Nydam finds.

Here is what I mean: |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

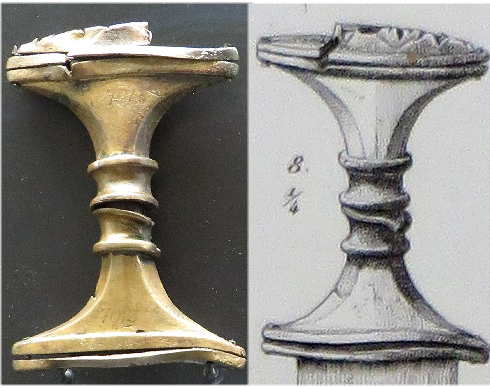

The two swords are presently in the Copenhagen

museum but apparently not on display. They are listed as No. 388 and 498 in 2)

and carry the stock No. 25 234 and 25 249, respectively. They are probably from around 350 AD. The hilt of the "palmette"

sword, however is in Schleswig: |

|

|

|

|

There are more swords found in Danish bogs with chevron and palmette

patterns; especially from Illerup Ådal. Not a lot but enough to

ascertain hat these patterns were routinely made. This link shows details.

Chevron and palmette patterns are quite interesting for a simple reason: How does one make patterns like these? And combinations

thereof? Sometimes the chevrons are "filled" with palmettes; sometimes with something else - at last this is claimed

in the literature. One example is shown here. |

|

|

How does one make pattern welded swords with chevron or palmette

pattern? Good question. Looking at just the palmette pattern, one way would be to first making rods with a palmette cross-sectional

pattern. Then cut your rod them into thin slices, which you weld on the blade, little piece by little piece.

This leaves

the question of how you make a rod with a palmette cross-sectional pattern? I simply don't know. I could guess but so can

you; keep in mind that these guys also knew how to make wires

that could be used for making finer structures. But even if you have a "palmette" rod, how do you cut it in thin

slices? Precision metal saws did no yet exist.

More to that in the Illustrations module. Here we simply note: |

|

|

| |

|

Nobody seems to know how

chevron / palmette patterns were made!

|

|

|

Several authors deal with the problem by not mentioning it (e.g.

the Illerup Ådal (Vol. 11, 12) books

or J. Ypey's article 1)). I do have some

ideas, though. |

|

Now let's consider that I have answered - to the best of my ability - the first

question: how to make complex patterns. It's time to look a the other questions |

| |

| |

| |

Quickies |

|

What I'm going to do now is to run very briefly through some of the other questions

from above. Here goes: |

|

Question No. 2: Was anything else made by pattern

welding? How about sax blades and lance heads, for example?

Answer: Yes. |

|

|

However, typically far less often, and mostly (but not always) less

elaborate, as far as I can tell. If one looks at all the graves were some important person was buried with a sword and a

sax, chances are that the sword was pattern welded and the sax was not.

A few lance heads out of thousands were decorated

with patterns, sometimes elaborate. |

|

Question No. 3:: Were pattern welding techniques used outside of Northern Europe? When? What for and how?

Answer: Yes. Most of the time, mostly for show, and more or less as described above. |

|

|

Seriously now: Whoever worked with iron and steel at any time after, say, 1200

BC had to make a sword or anything else not too small by some kind of piling

- except for the people using crucible steel. At the very least you had to "pile" your bloom. It is unavoidable

that on occasion a random pattern results, and it is equally unavoidable that somebody somewhere sometime started to develop

piling to a point where the pattern is no longer random but intended. In particular if Mr. somebody had seen a true pattern

welded sword that somebody else had brought back as a souvenir from his business trip to Northern Europe. In contrast, some

others like the Japanese might have gone for rather tricky structural and compositional piling but without the intention

to produce a pattern.

Be that as it may, it is now time to clear up a few statements about he iron / steel technology

of "The Others" that come up all the time and rather confuses the issue.

- Nobody on this globe could make a sword that comes close in complexity to the pattern welded swords of the Celts / Romans

after about 200 AD or even much earlier.

- Statements like: "For Japanese Samurai blades several thousands of layers were welded together,

for oriental damascene (meaning wootz) we have a few hundred, and the Indonesian Palmor

has a few dozen. In Europe, however, one rarely exceeds ten layers"

1) (my translations) are pure BS. The statement not only confuses faggoting with piling, it also assumes that the quality improves with the number of "layers".

We know that some North European sword smiths used faggoting because of Maeders's fine analysis, and we can assume with confidence that it was

done most of the time as pointed out before. They had "thousands of layers"

too, in other words.

- But what about the Chinese? Well - read this module. I

do not doubt that "the Chinese" made fine swords around 200 AD, too, but I challenge you to prove that they made

one that was more complex or simply better than some of the finest Nydam / Illerup swords.

This is about iron and steel technology. So far I have not found a convincing reason that other areas on this globe

were ahead of the Europeans as far as working with bloomery iron and steel was concerned. |

|

Question No. 4: How do pattern welded swords fit

in with Celtic, Roman and Viking swords, and so on?

Answer: It should be clear by now that the prime examples of pattern welded swords from the

Danish bogs were from Roman "factories". That doesn't exclude the possibility that the were actually done by Celtic

smiths who in 200 AD had become Romans.

|

|

|

The term "Viking" refers to people living in Scandinavia (including

parts of what is now Germany) from about 800 onwards. Their swords are a kind of in-between the old pattern welded after-Roman

sword and the new "Ulfberht" all-steel type sword. I'll get to that. |

|

Question No. 5: What about quench hardening of pattern welded blades? Was it done at all and if yes, was it really

similar to the famous procedure used for Japanese swords?

Answer: Yes. And: maybe. |

|

|

This is a bit tricky. A smith might have quench hardened a blade by dunking it

in water without having hardening in mind; maybe he just wanted to shorten the cooling down time. A smith might have conscientiously

quenched his blade to induce some case hardening but failed because he didn't do it right (too shortly, for example) or

because the steel he used for the edges was too low in carbon. Maybe he had phosphorus steel that can't be quench hardened,

or worse, a steel with both phosphorous and carbon (plus God knows what else) where all kinds of things can happen during

quenching.

Only quench hardening produces martensite in "normal " carbon steel. Metallographic analysis of

pattern welded swords did find martensite in some steel edges, so quench hardening was employed. And why not? We know that

the earlier Celtic La Tène swords were not quench hardened while some early (not yet pattern welded but laboriously

piled) Roman swords were. However, in other samples martensite is absent - indicating either no quenching or failed quenching.

Was differential quenching used (that's the fancy name for what the Japanese did much

later)? In other words, was only the cutting edge exposed to high cooling rates by protecting the bulk of the blade with

some clay? There are some indication for this this - but it is too early to tell.

I'll come back to the topic later |

|

Question No. 6: How does pattern welding relate

to Damascus? Are "damascened" blades better than others?

Answer: The answer to the first question is clear; I have dealt

with that already: pattern welding has nothing whatsoever to do with Damascus. |

|

|

The second question is a bit more tricky to answer. Yes,

"damascened" blades are better than others because "damascened" or pattern welded blades had to be made

with great cunning and care and thus were better than some banged together discount swords. No,

because you can't beat a sword made from piling good homogeneous steels without producing patterns. Maybe

because a composite of tightly interwoven rods of relatively bad steels could be better

than a simple structure made from these steels. More to that later. |

| | |

|

|

Question No. 7: What about the revival of pattern welding in the 19th century?

Answer: A very tricky question with no easy answer. I will perhaps write a special module

as soon as I see "the light". Until then just a few points: |

| |

|

First let's look a the "facts" as far as I know them. Much of what follows

is from Manfred Sachse's classic book.

- Pattern welding went never out of style in the "Orient". In contrast to Europe it was used for all kinds of

things in Turkey and farther East, including armor, the Indonesian Kris, and in particular gun

barrels.

- When guns an pistols became private items for hunting (or duelling) in the 17th century, the "West" became

aware of the "Eastern" pattern welded gun barrels and started to import these items. That happened around the

end of the 18th century, i.e. 1680 or so. It is certainly connected to the general awareness of "the Turks". First

because one needed to throw them out of Europe (look up the 1683 "battle of Vienna", featuring the super-hero

Prince Eugene of Savoy), and second because the Turkish culture and way of live made a big impression on the Europeans;

witness, for example, the collection of "Turkish" things by August the Strong, Elector of Saxony and later King

of Poland (1670 – 1733), now on exhibition in the "Türckische

Cammer" (Turkish Chamber) in Dresden.

- However: military guns of all sizes in Europe were always made from one kind of

(more or less) homogeneous steel or cast iron (if not from bronze or brass) and never by pattern welding. Private pattern-welded

guns appeared around 1780; and some French, Belgian and English guys were instrumental in this.

- At the beginning of the 19th century several European places made "Turkish damask",

foremost Liège in Belgium. It was a big industry and huge amounts of pattern welded gun barrels were made. An example of a catalogue is shown here; the real thing is right below.

- As far as swords are concerned, piling and pattern welding went out of style after - roughly - 900 AD and was completely

abandoned around 1200 AD in favor of all-steel swords. These swords were typically piled with softer steel inside. They

would not have shown a pattern. More or less in synchronously with pattern welded gun barrels, pattern welded blades became

fashionable again and a "damascened" sword was common in the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century

in Europe.

The picture below illustrates what I'm talking about. It's a close up of a two-barreled gun with a torsion

"damascene" pattern. It's done by the usual production of a twisted striped rod plus grinding. Then the patterned

long strip is wrapped around a core, followed by fire welding. The final step is reaming the bore and straightning by experts.

Complicated but not really of much interest to us because (in Europe) it is a 19th century technology. |

| |

|

|

|

| Pattern welded gun barrel and how it's done |

| Source: Photographed in the weapon museum in Suhl, Germany |

|

|

|

The problem I have with all of this can be put into two question:

- How does the revival of pattern welded "damascene", somehow triggered by "Turkish damascene" tie

in with the craze about wootz steel and blades around the

same time? Note that any terms containing the word "damascene" in connection with patterned blades from the East

could mean wootz blades or pattern welded blades, and possibly also blades with encrusted designs.

- How did the general ubiquity of contemporary "damascene" swords and things

in the 19th century influence the interpretation of the ancient pattern welded swords

dug up systematically after about 1850? In other words: Did Conrad Engelhardt, when he dug up pattern welded Roman swords,

recognize immediately that he looked at "torsion" damascene and so on? He did mention "damascened swords" but it is not clear what, exactly, he meant.

It is quite clear that there was some confusion - or better a lot of confusion - about patterns produced by using

crucible steel ("wootz") and by pattern welding. We also know of bitter fights concerning the difference in quality

of "damascened" blades vs. single steel blades, including increasingly cast steel. Nevertheless, how all of that

connects is not clear to me. Do no forget that as late as 1819

the science titan Faraday made completely wrong pronouncements about the nature of (wootz) steel.

The second question

is open. It will come up again when I deal with the history of discovering ancient pattern welding. |

|

Question No. 8: How to treat the surface to reveal the pattern. Is "Japanese polishing" better than "normal"

polishing followed by some etching?

Answer: Before I go into this, I advise you to look up this

module. |

|

|

OK, now that you are back, I can elaborate a bit about what that question implies.

"Polishing", in the broadest possible meaning, entails one or several of the following points:

- Generating the basic geometry of the blade surface by "polishing" (or grinding) off surplus material. A flat

surface where this is wanted, a nice round fuller, or two, and so on. The surfaces should be reasonably "shiny".

- The surfaces should be like mirrors, not showing any structure.

- The surface should reflect the internal structure right after finishing polishing.

- The surfaces should be good enough to allow some kind of chemical etching to produce a pattern. Either the macroscopic

pattern intended by pattern welding or the microscopic pattern intended for structural investigation with microscopy.

- The polishing should keep lines and ridges perfectly straight and ridges sharp.

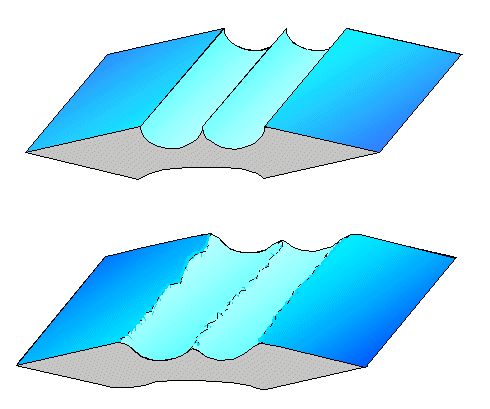

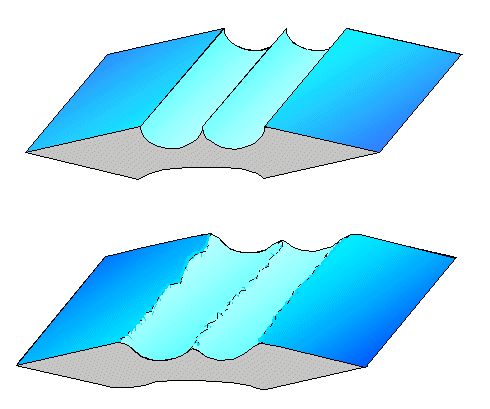

The last point needs explaining; best done with a figure showing a sword with fullers in cross-section: |

| |

|

Top: Ridges / Edges perfectly straight and sharp after polishing.

Bottom: Ridges / Edges rounded and somewhat wavy |

|

|

|

The bottom one would look ugly and would be totally unacceptable, of course. However,

the fighting value of the ugly sword would be just as good as the one with the perfect structure. In other words: |

| |

|

"Polishing" is mostly for show!

|

|

|

|

So what about the Japanese method of polishing a sword blade that, according

to Stefan Maeder, is so much better than what "we"

did and do? In essence, Japanese polishing is a combination of point 3 and point 5 from the list above. It defines lines

on the blade with the utmost precision and it reveals structures. The first part is not mysterious, it is just very advanced

precision work.

How does Japanese polishing reveal structures? And which structures exactly? Who knows; I have yet

to see a scientific investigation of "Japanese" surfaces. The principle is clear, however. If the polishing particles

in your slurry are harder then regular iron / steel, but softer than martensite, for example, the surface structure on the

iron / steel part will be different from that on martensite, and that means you can "see" it.

Find out more

by reading the special module | |

|

|

Enough! The last three questions left (No. 9 - 11) will be dealt with in the next

module. |

| |

| |

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)