| |

11.3.3 Evolution of Pattern Welding |

|

We still have three questions to deal with |

| |

- The history of the making of pattern welded swords. Who made the first ones when

and where? How did the technology develop and spread?

- The history of the discovery of the pattern welded swords. How many have been dug

out when and where. Where are they now? What kind of investigations took place? Why are the Danes so pissed about the Nydam

treasure in Schleswig?

- Most important: The metallurgy of the pattern welded sword. What do we know and

what do we guess?

The last questions merits its own sub-chapter. I will deal with questions No. 9 and 10 right here.

|

| |

|

| |

History of Pattern Welding |

|

I have put a lot of emphasize on the pattern welded swords found in Danish bogs.

Almost all of them were from Roman work shops that were supposedly located somewhere in South Germany / France or along

the river Rhine. The "Romans" who made them might have been Romans in the same way as the guys who produced the

atomic bomb or rockets were Americans. The "Romans" in South Germany used to be members of Celtic tribes before

they were coerced to become Romans. Later (after 200 AD, say) they gradually turned into Alemanni (more or less forcefully)

before they became (very forcefully) Merovingians and then members of the Carolingian empire.

A number of bog-swords

from around 300 AD where made with pattern welding skills that could not be improved upon then or now - provided you work

with bloomery iron / steel and a manually wielded hammer. So let's consider 300 AD as the point in time when pattern welding

technology climaxed. |

|

|

Looking at the history of pattern welding we thus need to ask

two questions: - What happened before 300 AD? How did pattern welding evolve?

- What happened after 300 AD? How did pattern welding go on and eventually decayed?

|

|

|

Besides the history of pattern welding, there is also the history of discovering

the pattern welding of old. It is one thing to find an old pattern welded blade, and quite another thing to recognize it

for what it is. The basic concept of twisted striped rods is not so obvious if you (and everybody else you know) has never

heard of that. I will give that topic a quick look, too. |

| | |

|

How Pattern Welding Evolved Before 300 AD |

|

How did pattern welding evolve? Who knows. There are no written records and what

has been dug out of bogs and graves does not mirror the distribution of pattern welded swords 2000 years ago. There are

far more Roman pattern welded swords in museums in Northern Europe than in Italy or Southern Europe because the barbarians

up there sacrificed a lot of swords in bogs where iron was preserved and they put swords

into the graves of the warriors. The Romans did neither. We need to go for educated guesses based on the few things we do

know.

It is helpful to realize that here is a continuous transition from random

structural piling to pattern welding of complex patterns. Since all cultures working with bloomery iron had to do some

piling for making products, it was unavoidable that:

- Structural and compositional piling developed, e.g. by using hard steel on the outside

of a blade for the edges. The Roman "Thames" sword from the 1st / 2nd

century AD offers a good example for a thoughtful way of structural and compositional piling that did not

produce a pattern. It was essentially made from one broad striped rod.

- Random patterns were produced on occasion and must have made people aware of the

aesthetic potential of compositional piling.

Eventually striped rods became standard, producing not only a pleasing pattern but preventing sudden and complete

fracture, especially in cold weather, for all swords employing

phosphorous steel for the harder parts. Many in-between situations are imaginable and that means there is no definite beginning

of pattern welding. The Celtic (La Tène) swords bear witness to this. Some swords had their iron / steel parts piled

in such a way that a pattern might have resulted, possibly without the smith being aware of that. Contrariwise, another

smith might have attempted to produce a certain pattern and failed.

At least one Celtic smith making a "La Tène sword" around 300 BC (No. 12 in the picture accessed by this link) produced a complex pattern welded sword that looks suspiciously like one of the the

more complex pattern welded swords made about 600 years later. Far be it from me to doubt Pleiner's analysis of this sword.

But this sword just doesn't make sense. It is possible that a particular talented La Tène smith was 500 years ahead

of the rest, it's just not very likely.

Then again, in 2015 (after I had written this module), two Celtic swords (with

anthropoid hilts) and pattern welded blades turned up in an auction catalogue! The pattern resulted from simple striped

rods that might have been employed for increased fracture toughness but it sure looks like a pattern was clearly intended.

Here is a detailed picture of one blade and here

are the descriptions from the auction catalogue.

Yet more amazing is the celtic blade from the middle La Tène

period (2nd century BC) that came up somewhat later in an auction in April 2016. It definitely employs two very well made

twisted stripes rods. Here is

a picture and the description from the auction house. |

|

Let's see what seems to be definitely known as we ascend upwards in time: |

|

| Sword Data; Time / Place |

Pattern / Structure |

Source |

Middle Latène (250 BC - 150 BC)

- Unknow location

- Unknow location |

Structural piling;

face welding appears.

- 2 striped rods (and anthropoid iron

hilt)

- 2 twisted striped rods

First indications for twisting.

Not in sci. literature |

Pleiner; Lang & Ager

- Antique

trade

- Antique trade |

Late Latène (150 BC - 0) swords

- Heiligenstein / Speyer (Germany)

- Llyn Cerrig Bach/ Anglesey (England)

|

Three striped rods all through the blade. - Phosphor contrast.

|

Ypey

Lang & Ager

Antique trade |

Late Latène

Sword with full pattern welding

- Cuvi (Italy)

|

First known example with twisted striped rods and complex structure in the sci. literature.

This is the fully pattern welded No 12 sword of Pleiner |

Ypey

Maeder

Pleiner |

Latène swords found in

- Wachock / Ilza (Poland)

- Saône

/ France

- Museum Rouen / France

- Port Switzerland |

Some pattern welding. | Ypey

Maeder |

| No Roman pattern welded swords

from the 1st century AD. | |

As stated by:

Ypey |

However, from the 1st half

of the 1st century AD we have Pugios

with stripe patterns from

- Munich, Germany

- Leuven, Nijmegen, Velsen (Netherlands);

- Mainz (Germany) |

Most Pugios, however, are not pattern welded. The ones

that are seem to have pattern welded stripes only for decoration.

Typically the "classic" 4/3 iron/steel

layer package was used. | Ypey |

Spathae, around 200 AD

- around Oslo; (Norway) with Victoria/ Mars incrustations

- South Shields / Durham (England)

- Lauriacum / Linz (Austria) spatha |

Fully pattern welded

- 5/4 low/high phosphorous steel plates; some twisting.

- 2

counter twisted rods.

- 6 torsion strips on both sides! | Ypey

Maeder | Around 300 AD

Danish bog spatha |

Climax of pattern welding technique | |

500 AD - 1000 AD

In England |

Percentage of pattern-welded blades rose dramatically after »

500 AD, peaked to » 100 % during the 7th century, and fell again during the 9th / 10th centuries.

After 800 AD swords with pattern-welded

inscriptions appeared |

;

as far as investigated by

Lang & Ager |

|

|

That is not particularly illuminating. But what, exactly, is it that we want to

know? It is quite simple. We want to know how the following three techniques originated and evolved:

- The making of striped rods; including the selection of "bright and "dark"

steel.

- The twisting / grinding of the striped rods.

- Faggoting of the two materials before making

a striped rod.

How, where and when? From the above one might guess that pattern welding evolved in Celtic regions north of the Alpes.

But we simply know too little in general, and next to nothing about the use of faggoting in particular. And let me say it

once more: If low / high phosphorous steel was used for the bright / dark parts, no clear pattern could result without first

faggoting, i.e. homogenizing the phosphorous concentration, since phosphorous is always distributed rather inhomogeneously

in the "raw" iron /steel. And phosphorous steel was used a lot! |

|

|

Did you appreciate that I have hidden a contradiction in terms in the statements above? No?

I thought so. Let me explain: If you are able to select the right steel grades and you

can do faggoting, you do not need to go into pattern welding at all. You could make a superior all-steel swords right away.

That pattern welding nevertheless dominated sword making (but not sax making) for about 3 centuries then tells us that:

- either the conditions above were not fully met, then pattern welding might have made sense,

- or they were met and pattern welding made no sense from an utility point of view - but people liked to have "pretty"

swords.

The compromise was the full-steel sword with a pattern welded "veneer" that we find so often around and

after 300 AD. |

|

It is not clear to me when the first striped rod was made. The "Hermann Historica"

sword shown here definitely shows two striped rods running the length

of the blade. A (better preserved) second sword looks like it also incorporates striped rods but the catalogue picture are not conclusive.

|

|

|

Unfortunately no provenance is given for these swords. They are supposed to be Celtic and

from the middle La Tène period (3rd century BC). While there can be no doubt about the Celtic origin of these remarkable

swords, the dating is not beyond reproach since Celtic swords

with an anthropoid hilts are typically assigned to the late La Tène (1st century BC) period.

We thus can

be sure that Celtic smiths understood and used pattern welding with striped rods as early as about 100 BC, possibly earlier.

We don't know, however, if Celtic smiths invented pattern welding with all that implies or if they imported the technology

from somewhere else. While I'm not aware of pattern welding being practiced outside of Europe in the first few centuries

before the common time, that doesn't mean much. We may not have discoverd the relevant artifacts or we may not have given

them proper attention. Having said all this, I nevertheless like to state: |

| | |

Pattern welding was invented by

Celtic smiths sometime between

300 BC and 100 BC.

|

|

| |

|

The Celts used the technology, and so did the Romans. Around 300 AD pattern welding was routine

and "Roman" blades with incredibly complex strucures were routinely made. However, we do not know much about the

time between 100 BC and 300 AD. |

|

Let's stop here and look at the second point

from above: What happened to pattern welding after 300 AD? |

| | |

|

| |

How Pattern Welding

Matured Between 300 AD - 600 AD |

|

Good headline - I just don't know much about the topic. All I could figure out

so far is that "late" pattern welded swords were found in graves all over (Northern) Europe. I have no idea about

statistics (percentage of graves with swords, percentage of pattern welded swords, where and when) and thus will give you

only a few numbers from one tiny area for the beginning: |

| |

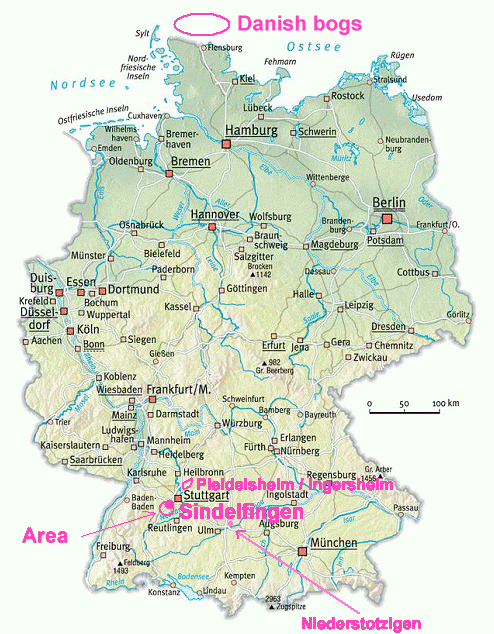

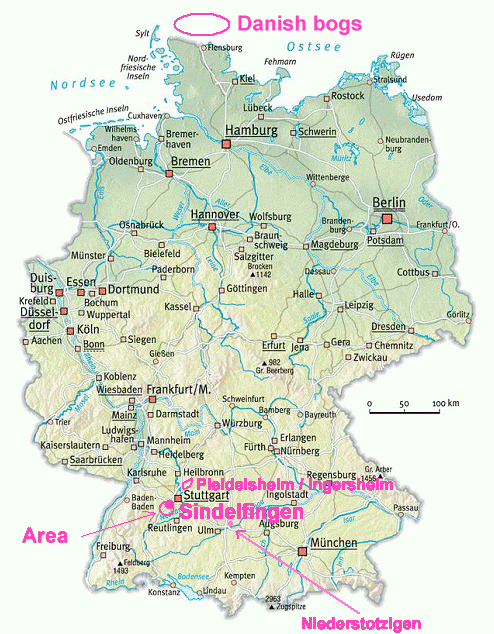

| | Area of "Sindelfingen swords" |

|

|

Sindelfingen is a town about 15 km south-east of Stuttgart, sporting a large Mercedes

plant. It is likely to be an Alemannic settlement like all

towns in South-West Germany with names ending on "-ingen". The Allemani graves in the Sindelfingen area are by

no means special; there are plenty similar ones all over South Germany. I only focus on them because Dorothee

Ade compiled a detailed analysis of what has been found in the Sindelfingen area in her 2012

PhD thesis. Most of the stuff is from ancient cemeteries, some from single graves.

Starting about 1860 people payed

some attention to artifacts from old times other then treasure that were occasionally dug up, and some of the stuff ended

up in museums. Nowadays the location of several ancient cemeteries are known but the graves are left alone for future generations

of archaeologists. We already know of another Alemannic cemetery in Pleidelsheim,

just to the North in the map above, and unexpected finds are made all the time, too (see below). |

|

|

I'm talking mostly about Alemanni graves here. The Alemanni, as pointed out before, coming from the North (and East), crossed the Roman Limes,

the fortified boundary "wall", in 260 AD and occupied parts of what is now South

Germany, Switzerleand and France. After the official end of the Roman empire in the second half of the 5th century,

the Alemanni were more or less dominated by Ostrogoths in the East or the Frankish Merowingians in the West. The Alemanni

were nevertheless a culture that has left deep traces until their nobility was wiped out for good at the "blood court at

Cannstatt" (Blutgericht zu Cannstatt) in 746.

What happened was that Carloman,

the eldest son of Charles

Martel, Charlemagne's grandfather, invited all nobles of the Alemanni to a council at Cannstatt (close to

Stuttgart). Carloman arrested the several thousand noblemen who had followed his invitation, accused them of taking part

in the uprising of Theudebald, Duke of Alamannia and Odilo, Duke of Bavaria, and summarily executed them all for high treason.

The action eliminated virtually the entire tribal leadership of the Alemanni and ended the independence of the duchy of

Alamannia, after which it was ruled by Frankish dukes. Things like that happen when you neglect to invade Gaul (now called "France") from time to time! |

|

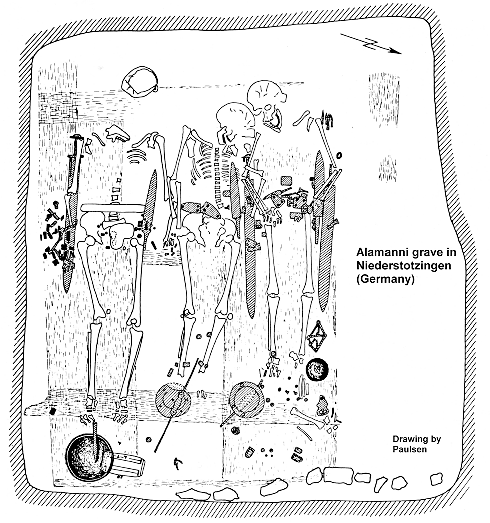

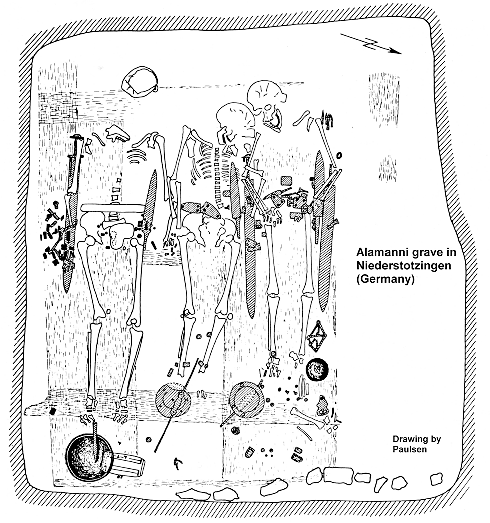

Anyway, the Alemanni buried their mighty ones with their weapons,

and that included pattern welded swords. Here is an especially interesting burial in Niederstotzingen

from around 600: |

| |

|

Alamanni grave in Niederstotzingen / South Germany (about 600 ±)

Large picture plus a picture of the real things |

| Source: Old drawing shown in many places, e.g. here

or in Menghin's book |

|

| |

|

Three warriors, each fully equipped with a big sword,

a sax, and many smaller items. And one of those warriors was - surprise! - a woman as a relatively recent DNA analysis proved

2).

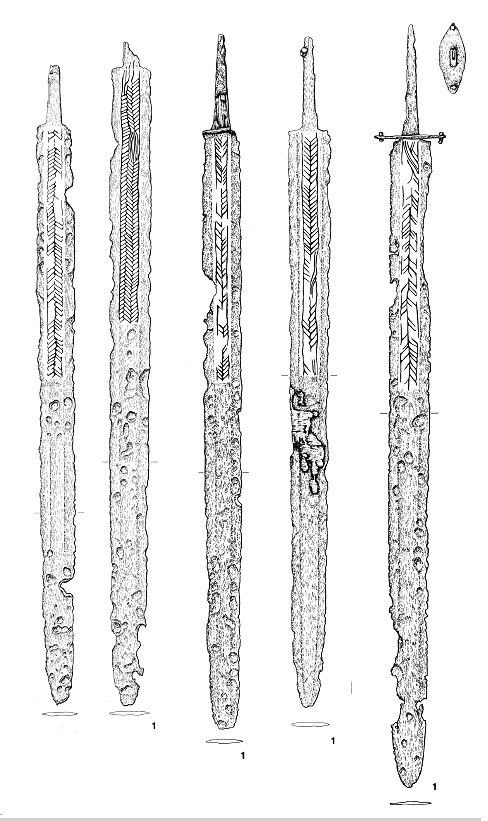

Here is what those swords might have looked like: |

| |

|

|

|

You don't want to see drawings but the real thing? OK - here are

some of the newest ones: |

| |

|

Arian (left) und Tarik Wissendaner show what they found

in 2012 while perusing an Altingen construction site. |

| Source: Local newspapers |

|

| |

|

Altingen is on the edge of the circled area in the

map above. While South-German museums are full of (pattern welded) Alemanni swords, there seem to be very few pictures around.

Manfred Sachse showed a good one in his book, and this link hub leads to a few more.

I have also started to take pictures myself; here is one (large scale) example. Even more pictures can be found

in this link |

|

So what do we know about the Alemanni swords found in the "Sindelfingen"

area? Here is a list of what was found in just a few places in the area investigated: |

| | |

| Place | No. graves |

Graves with

Spatha |

Graves with

Sax |

Time Horizon |

| Hailfingen |

661 | 25 |

3.8 % | 41 |

6.2% | 500 - 525 |

| Schretzheim |

630 | 105 |

16.7% | 82 |

13.4% | 500 - 525 |

| Holzgerlingen |

302 | 12 |

4.0% | ? | ? |

» 550 |

| Nusplingen |

278 | 15 |

5.4% | ? | ? |

» 550 |

| Marktoberdorf |

238 | 24 |

10.1% | 68 |

28.6% |

» 550 |

| Esslingen-Simau |

222 | 16 |

7.2% | 52 |

23.4% |

» 550 |

| Sontheim | 197 |

17 | 8.6% |

26 | 13.2% |

550 - 600 |

| Heidelberg-Kirchheim |

149 | 10 |

6.7% | 13 |

8.7% |

» 500 |

| Güttingen |

113 | 9 |

8.0% | 22 |

19.5% |

» 590 |

| Sindelfingen |

? | (21) |

? | 28 | ? |

450 - 500 |

| Sums / Averages |

2.790 | 233 |

8.35% | 332 |

15.02% | 450 - 600 |

|

|

|

Even if half the graves were for (unarmed) females, it is clear that

not all men and women had a sword. But whoever had a sword was very likely also in possession of a sax. Some, however, had

only a sax. By the way, the town names ending in "ingen" signal Alemannic origin. In contrast, the ending "Heim"

(=home) signal Merovingian dominance. From some towns it is known that the name changed after the Merivigians took over,

e.g. from Hessingen to Hessigheim. |

|

Pretty much all of the swords in the table above were pattern

welded. The first blades without pattern welding were from the beginning of the 7th century and their number increases towards

the end of the 7th century. As far as one can tell, exclusively twisted striped rods were used for pattern welding, producing

simple herring bone patterns (like in the picture above or here)

or more complex ones like in the "Ingersheim sword"

(almost in the area discussed above). No complex chevron or palmette patterns

have been found.

So much for the larger Sindelfingen area. But what about the rest of Europe? And for times after about

600 AD, when Sindelfingen ends? Tall questions with very short answers:

- As far as sword blades are concerned, the technology appears to have been about

the same everywhere in (Northern) Europe. Pattern welding was the standard. However, I have yet to see blades that surpass

the 350± Nydam / Illerup blades. Around 600 AD the first sword blades that are not pattern welded but made by laminating

pieces of supposedly faggoted steel appear in some areas (like South Germany). In other areas (like England) that transition

might have happened somewhat later. Pattern welding, however, never went quite out of style for another 400 or 500 years.

- We need to be a bit careful about the statement above. A corroded pattern welded blade might just appear

not to be pattern welded. Look a the one right below or the ones in

the link. Was pattern welding involved in the one below? It doesn't look like it but only X-ray pictures or metallographic

investigations will tell for sure. Indeed, more recent X-ray investigations

did produce evidence that pattern welding was used for blades that did not show it. Contrariwise, a blade with a clearly

visible pattern could have been made from solid steel while the pattern was only encrusted, inlayed or "damascened"

into the surface of the blade.

- In contrast, while there are some pattern welded saxes, the majority of that "utility

weapon" seems to have been made without pattern welding. To what extent piling and faggoting was used I can't tell.

- What had happened with respect to making pattern welded blades between - very roughly - 400 AD and 700 AD was and is

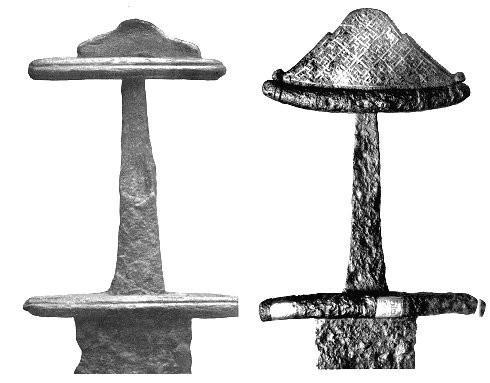

totally eclipsed by what had happened to the hilt.

That was true then and is true now. There are far more papers in the present literature about hilt details than about blades

for that time span.

- In other words: For the top-of-the line "show-off" swords the hilt became the distinctive part; it also must

have been far more expensive than the blade. That doesn't mean that the blade was not top; it just means it wasn't used

for fighting. You don't use your Porsche, Mercedes or Bentley four-wheel drive luxury off-road car to actually go off-road

either. For menial jobs you have other cars, not to mention people, for God's sake. But your Porsche would be up to the

job! We just don't have all that many fighting swords from that period, not to mention

that warriors might have used a sax for that.

|

|

In other words: As far as steel technology and pattern welding is concerned, the

technology was established and didn't change much for several centuries. That the focus shifted to the hilt was then to

be expected. Basic car technology with respect to the "mechanics" of cars became an established technology around

1980. Gone are the times when young men (like me and my buddies) discussed at length and with a lot of emotions the relative

advantages and shortcomings of suspension systems (Längslenker, Querlenker, Schräglenker, Raumlenker... there

are no English terms because the American car industry has yet to discover those techniques). Nowadays the sound system

of your car is far more interesting than the suspension system.

In other words: |

| |

|

| | |

|

| Gold hilt spatha, Stotzingen, Germany; Ellwangen museum |

Source: Left: Ellwangen / Germany museum

Right: "Photobucket", Matt Bunker's (medicusmatt) picture |

|

| |

|

Is that a pattern welded blade? It doesn't look like one but one must be careful

in making such a judgement. It was certainly a sword for showing off. Gold was and is in short supply in Northern Europe,

and the little that was panned around the Rhine must have been very precious. I doubt very much, however, that a sword with

such a hilt would have been any good in a fight. It has no pommel, must be badly balanced, and easily slips out of your

hand. |

| |

Gold hilt spatha were in use from about 450 AD – 490 AD

and are seen by some as derivatives of Romano-Byzantine designs. Alemanni mercenaries, serving in the army of the Byzantine

empire, might have brought them home as a kind of memorials and show-off piece. after they This

link, this one, and in particular

this one gives a few more pictures. King Childeric's sword from about 480 AD embodies the culmination

of the gold hilt sword and also leads over to the lavish use of almandine

(red garnet) and gold adornments in the time span from (roughly) 500 AD - 700 AD.

The gold hilt swords could be seen

as the first step into the new fashion of emphasizing the hilt. This is not so interesting to us here (we are into steel,

not gold, after all), so I only give you a (long and lavishly illustrated) special module on the hilt business. |

|

|

|

Hilt fashion development, however, is good for something: dating swords! Hilt fashions changed more quickly with time than blade fashion, just

look at the years before about 300 AD. Certain types then are seen

as typical for certain times and areas. Fancy hilts, containing gold, silver or bronze, corrode far less than iron or organic

materials and often these parts are about all that has been left.

The reference for hilt fashions is still the 1939 book of Elis Behmer.

He sifted through much of what has been found in connections with swords, in particular the metal pieces

left from hilts and scabbards. Pommels, cross-guards, chapes, lockets and so on in later "migrations period"

years. Behmer's successor, up to a point, is Wlifried Menghin with his book "Das Schwert im frühen Mittelalter" (Swords

during the Early Middle Age).

It's all in the special module. We now look at: |

| | |

|

| |

The History of Discovering the Pattern Welded Swords of the 1st Millennium AD |

|

People must have unearthed 1st millennium swords all the time without looking

for them. Farmers unearth things, and so do builders, peat diggers and children. But interest in old things other than treasures

was not large before about 1750, when serious archaeology started by dedicated digging in Pompeii

and Herculaneum. It took another 100 years before old rusty iron found some interest, and yet another 100 years needed

to go by before the science of iron and steel had developed to a point where one could try to figure out what old iron /

steel artifacts could tell us.

Let's play the old game and ask: |

| | |

Who first noticed that he was looking

at the result of pattern welded twisted

striped rods when he contemplated an

old sword? When was that?

|

|

| |

|

I certainly don't know. I have sifted through 100+ old papers but couldn't figure out who

exactly had made the first decisive step in the right direction. But as we shall see, it will be sufficient to look a the

work of just a few prominent old researchers to arrive at a surprising insight: |

| | |

Something went spectacularly wrong!

|

|

|

Let's start with Conrad Engelhardt and the Danish bogs. Systematic digging there started in 1859 - 1863, look

up the special modules for details. Pattern welded swords were found

and recognized as such by Engelhardt. So what did Engelhardt state with respect to pattern welding? |

|

|

Engelhardt published

his findings in 1886 (in English) and referred to the swords unearthed in Nydam as being "damascened". This was

quite natural if unfortunate. Now let's see how Engelhardt described the process of "damascening" in 1886. |

| |

"The Nydam swords are of iron, long, straight, and two-edged; the blades

are for the most part - ninety out of a hundred - richly damascened in various patterns, and afford good illustrations of

the poet's sword, " the costliest of irons, with twisted hilt, and variegated like a snake" (Beowulf). Iron wires, arranged

in patterns, have been laid in grooves made in the surface of the blade, and then the whole has been welded together, so

that the surface must originally have been smooth. That we now see the patterns raised is probably owing to unequal oxidation.

Among the many elegant and ingenious patterns represented on Plates

VI and VII, l would call special attention to Fig. 5 and 5a,

with borders of flowers freely rendered in twisted iron wire."

Page 52 |

|

|

|

That is a description of "tauschieren", and there is

no proper English word with exactly that meaning; words like inlaying, incrustation come close. The proper word would be

"damascening" but that is now misleading since it was misused as another word for "pattern welding"

(mostly by Germans). Whatever - we note that Engelhardt in 1886 was obviously not aware of the twisted striped rod technique. |

|

Now lets move up to 1939 and look at what Behmer has to say. He studied the literature quite carefully, and if the "twisted striped

rod technique" was generally known by then, he would most certainly refer to it. |

|

|

Here is the decisive paragraph from his book: |

| |

"Im Zusammenhang mit den Blutrinnen tritt so gut wie stets Damaszierung

auf. In jeder Rinne sind dann auf dem Grunde längs der ganzen Klinge lange, parallele, einander kreuzende, gebogene

oder wirbelförmig gewundene Drähte, vermutlich aus Stahl, eingelegt, die in das Schmiedeeisen der Klinge eingehämmert

sind. Klingen, die keine Blutrinnen aufweisen, sind oft in ähnlicher Weise damasziert.

Der Zweck dieser „unechten" Damaszierung, die von der morgenländischen „echten"

Damaszierung, mit der das Abendland erst in der Zeit der Kreuzzüge bekannt wurde, wohl zu unterscheiden ist, dürfte

der gewesen sein, durch Einhämmern von Stahlstreifen in ein weicheres Material dieses stärker und elastischer

zu machen."

Page 38 |

"In connection with fullers we find pretty much always damascening. Each

fuller groove contains hammered-in wires down its whole length, probably made from steel, running in parallel or wavy, crossing

each other or forming eddies. Blades without fullers are often damascened in a similar way.

The purpose of this "untrue" damascene, that one should strictly distinguish from the "true"

damascene, that was only known to the West after the crusades, might have been to render the soft material more strong and

elastic by hammering in steel wires"

My translation |

|

|

|

54 years went by since Engelhardts publication, and nothing has changed! It is mostly but

not completley pure BS, mind you, since some swords have been "patterned" this way.

|

|

It was Herbert Maryon

in 1940 who coined the term "pattern welding" and, as far

as I can tell, had almost the right ideas about the striped rod twisting.

Next, in 1954, the year Germany won the soccer

championship for the first time, J.W. Anstee and L. Biek published "A study in pattern welding" 3) and related their results of attempts to replicate an old pattern welded sword by forging. Those

were probably the first attempts in "experimental archaeology" with respect to pattern welding. They did use a

kind of twisted striped rod and experienced big problems with fire welding. They did not only use striped rods but also

wires. The idea was to fill the grooves of the screw-like spiral obtained after twisting with a wire to obtain a smoother

surface in order to facilitate welding.

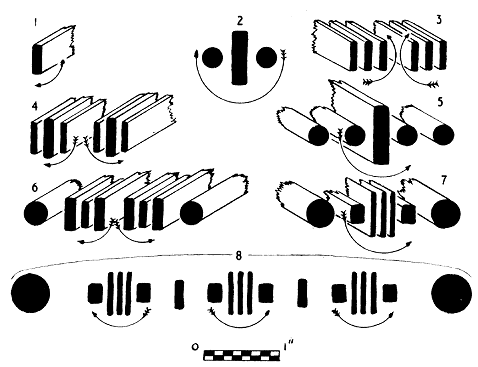

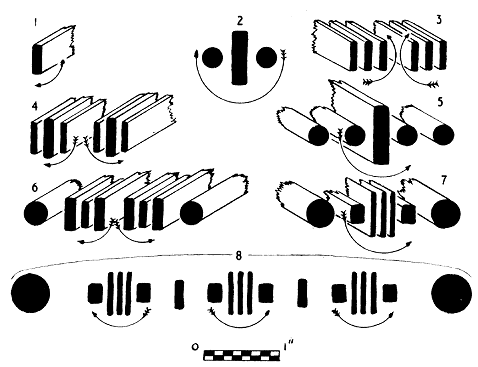

The essential picture of the paper tells it all: |

| |

|

| Anstee's and and Biek's geometries |

|

|

|

We do not need to go into details. It is clear that Anstee and and Biek came close but weren't

quite there yet. Here are a couple of interesting quotes:

- "Alternate strips of carbon-free and low carbon metal have been thought necessary to produce

such a pattern, and up to 0.6% of carbon has been reported in some material. As the present work shows, however, patterns

are obtained even with strips of the same, virtually carbon-free, iron".

The role of phosphorous

iron in pattern welding was not known by the authors. Here we probably have the source of the myth that patterns could be

produced with one kind of steel. That a pattern was obtained probably relates to their problems with welding:

- "Some of the difficulties inherent in this natural and apparently simple method of construction

were revealed when a number of such rods were made in the Laboratory. No welding was then possible; the twisted rods were

merely flattened, soft-soldered and ground away to varying levels to reveal the consequent changes in pattern."

What that means is that their weld seams, if "taking" at all, were likely full of oxides and thus could have

shown a "pattern".

- "Furthermore, the herringbone and other patterns observed, either on the surface or (on X-radiographs)

within this type of blade, could evidently be produced by (the remains of) composite rods, each pile-forged from thin strips

of iron, and adjacent ones twist-welded in opposite directions"

That is the correct idea.

- "The answer to the problem of scale removal was now clear. As during the work the oxide layer

became thicker (and duller) it was forced from all surfaces by the twisting stress. The best solution was to allow the scale

to form, twist a little, then tap the hot bundle with the hammer. In this manner the strips were finally screwed up on to

themselves, the whole length being traversed in short sections altogether four times-twice up and down. Even so, much fine

scale was left in the joints; nevertheless, all internal welds there appeared to be perfect, except at one or two points

where lumpy particles had been trapped."

- So twisting makes welding easier!?

|

|

I do not know when finally everything was

right - must have been around 1960. I do know something else, however: |

| |

The twisted striped rod technique was

an industrial standard in 1850 and earlier!

|

|

|

I have dealt

with that already - not so long ago. All of the guys named above must have seen pattern welded contemporary objects

like guns for hunting and military (dress) swords in their time. In the larger German-speaking areas (including Denmark,

etc.) these pattern welded objects were called damascened and were standard issue stuff.

While many smiths or companies employed the technique, mass production of twisted striped rod stuff took place in Belgium. |

|

|

How Engelhardt and Co. could miss that is beyond me and that's why I say that something went

spectacularly wrong. However, they were men of the pen and not the sword and therefore might have become early victims of

the "damascene" confusion, believing that the "damascened" gun barrels and swords they must have seen

were made by "tauschieren"=inlaying, encrusting; just as described by Engelhardt and Co. |

| |

| |

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)