|

Migration Period Swords and Fancy Hilts & Pommels

|

|

What It's All About |

|

Not much seems to be known about Elis

Behmer. But his one and only book "Das

zweischneidige Schwert der Völkerwanderungszeit" (The double-edged sword of the migration period) is still the

standard for our topic here. It was published in 1939, a time when "Germanic" stuff was prominent in Germany (and

Scandinavia); the book should be read with this in mind. Behmer's book is apparently his PhD thesis work1) and contains a huge amount of hard information in the form of (black-and-white) pictures of a large

number of objects plus detailed information about their origin and whereabouts. |

| |

|

Behmer established three main groups (A, B and C) for migration period swords,

with 4, 3 and 2 subgroups, respectively. In contrast to the classification given here,

Behmer does not consider the blades but looks at everything else, in particular the hilt (with pommel, grip, cross guard)

and the various metal parts associated with a scabbard (chape, locket, belt attachments etc.).

His classification of

the sword from the earlier periods (say 350 AD - 450 AD) is based to a large extent on the Danish

bog finds and thus overlaps with the modern systems.

However, for the time after 450 AD, his system is still the one everybody seems to use. |

|

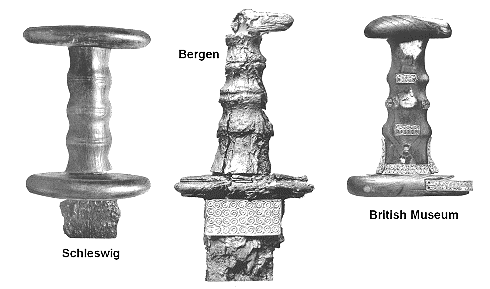

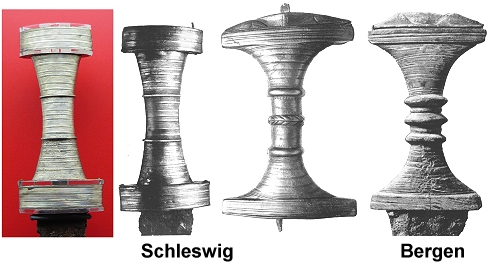

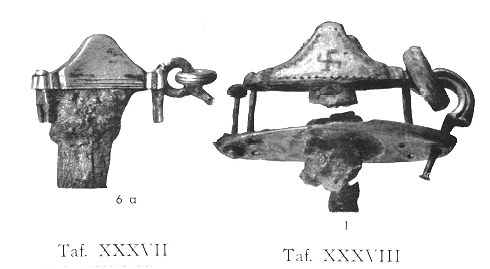

Here are a few excerpts. First the group A, subgroup 1 hilts: |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Typical group A, subgroup 1 hilts |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Behmer sees swords with this kind of hilts (and proper other parts) as the oldest "Germanic"

types. They are typical for finds in Danish bogs. The one the left is

indeed from Nydam and on display in the Schleswig museum.

There are also finds from graves, and according to Behmer this kind of sword was prevalent all over Northern Europe (including

England) around 300 AD - 400 AD. Since we know that a least the blades found in Danish bogs were all of Roman make, this

would indicate that the Germanic tribes used (pattern welded) Roman blades but attached their own hilts. This is quite possible;

there are indications from all eras that one and the same blade may have seen different hilts. It is, however, hard to prove.

Behmer, like many archaeologists, is reluctant to make definite statements. All the numbers given are therefore mostly my

interpretation of what he conceals in lengthy prose. |

|

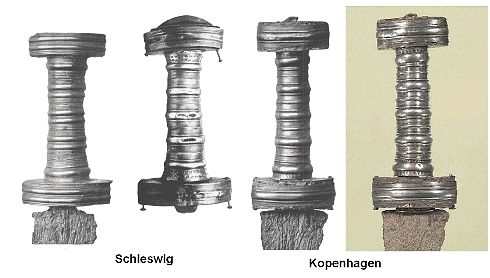

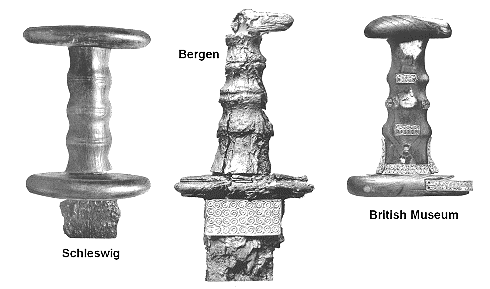

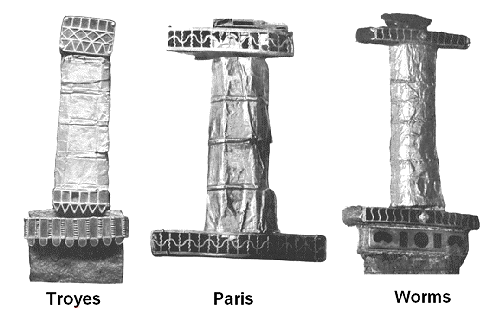

Here is group A, subgroup 2: |

| |

| |

| |

|

Typical group A, subgroup 2 hilts.

On the right a new photography of the real thing.

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

This type is more or less restricted to Denmark, typically found in bogs like Kragehul. In this case Behmer also looks at the blade in some detail. It is

typically narrow (4,5 - 5,5 cm) and pattern welded. The blades have fullers - up to six - and go back to the Roman spatha

for mounted warriors, says Behmer. The time horizon for this type is 350+ AD |

|

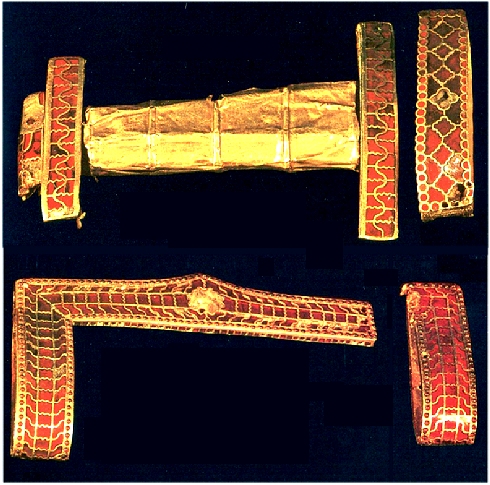

Group A, subgroup 3 is of some interest because it is the first

one to sport major amounts of gold (or silver). The hilt is covered with the noble metal and gold cells inlaid with almandine (a red garnets variety) in the cloisonné technique.

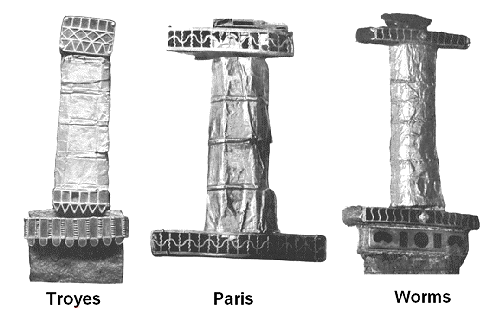

Here are pictures from Behmer: |

| |

| |

| |

|

| Typical group A, subgroup 3 hilts. |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The blade is broad and bears no resemblance anymore to Roman types (says

Behmer). The blades tend to have one (broad) fuller but "rich damascening is only found on exceptions". I'm not

sure if that is true since many of these blades are badly corroded and "damascening" is not obvious and only shows

up in X-rays (that Behmer didn't have).

I would tend to put the following sword hilts in the same category, and so does

Behmer: |

| |

| |

| |

|

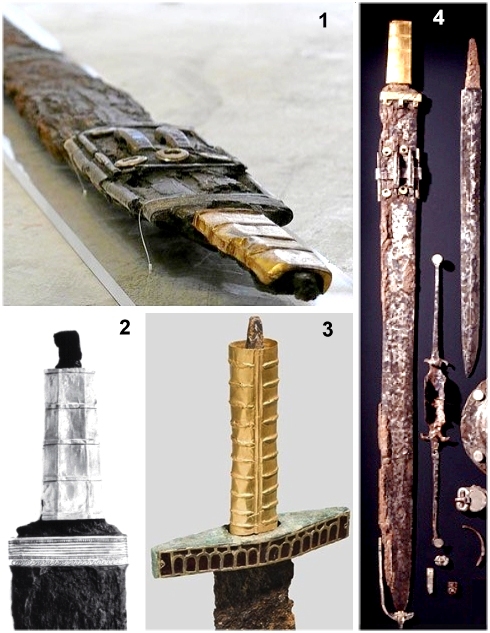

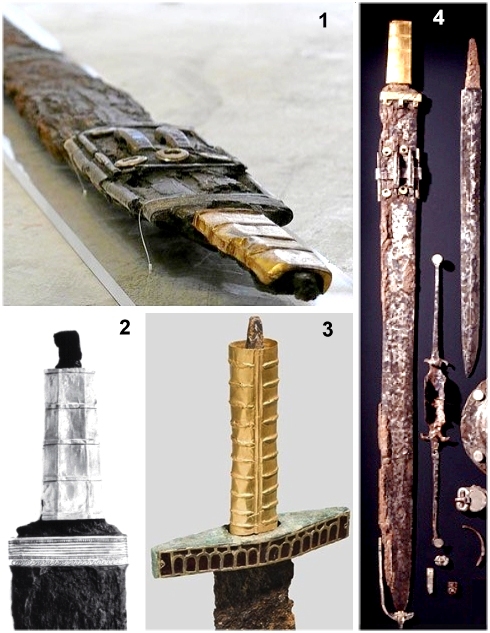

| Sword details;

1 Spatha from Gültlingen; 460 AD - 480 AD. Only the showy side of the hilt is gold; the gold is "Rhinegold".

Landesmuseum Stuttgart.

2 Spatha from Sindelfingen; rather similar to 1. Table 8 in Dorothee's

thesis.

3 Spatha from am 2006 auction (Hermann Historica). Supposedly from 375 AD - 450 AD and Eastern Europe. Estimated

at € 30.000 - €45.000.

4 Recently found spatha (plus sax etc.) from Pleidelsheim; ca. 400±. Rather similar to 1 again.

More pictures here |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The group A3 swords are the swords of the

Alemmani (or Alamanni). These swords spread from their homeland in South Germany

to the West, East and North, states Behmer. Well, maybe, but not in the way Behmer describes it. In his reasoning the "Heruli"

play a major role, an East Germanic tribe who migrated from Scandinavia to the Black Sea in the third century AD. The Heruli,

however, according to more modern insights, were not as important as earlier historians believed.

"Goldgriffspathen

" (gold grip spathae) appear around 450 AD – 490 AD and are nowadays seen (by some) as derivatives of a Romano-Byzantine

design. The culmination of this kind of sword was found in the grave of Childeric I, who died on 481 / 2 AD. We also have an early lavish use of red

almandine gemstones for decoration. |

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Childeric I (ca. 440 – 481/482) was a king of the Salian Franks, those Franks in the

North-East (present day Belgium, North France). He fathered Clovis I,

who would unite the Franks and founded the Merovingian dynasty

that eventually subdued and wiped out the

Alemannis . His sword, however, was evidently imported from

the Alemanni. Since it must have been made some time before his death we can date it to 450±.

His tomb, around

Tournai, Belgium, was discovered in 1653. The many precious objects it contained were kept in a library in Paris. In 1831

they were stolen and melted down. Only a few pieces survived including the pieces shown above. From the#rest we have only

drawings. |

|

I'll skip the peculiar but not so interesting group A, subgroup 4

swords (Eastern type) and continue with group B, subgroup 5. You know these hilts from Nydam

and especially Esbjol. |

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Those hilts are almost exclusively form Danish

bogs; they date to the end of the 4th century (380+) up to about 500 AD. Behmer includes some rather different looking

hilts from Norway in the same group; see below. I'm not sure about that. |

|

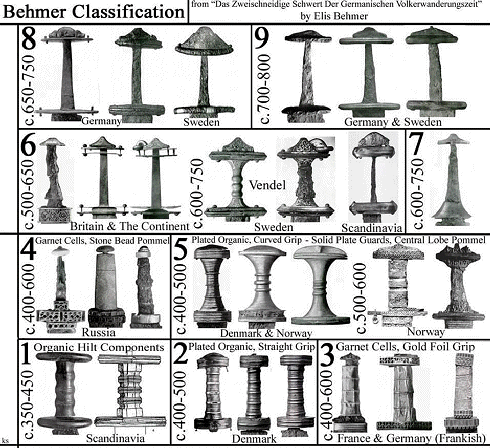

I could go on like this for quite a while but remember: This

is about iron and steel

and not about gold and jewels! So for the remaining subgroups I only give you an overview: |

| |

| |

| | |

|

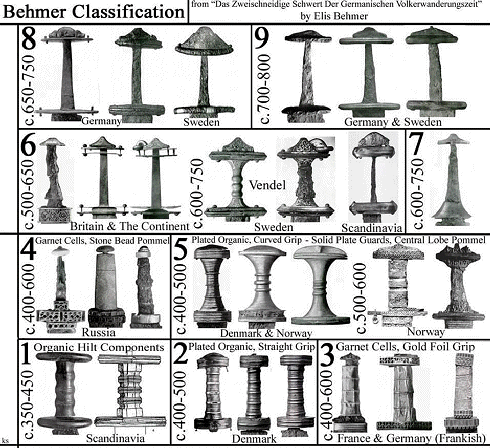

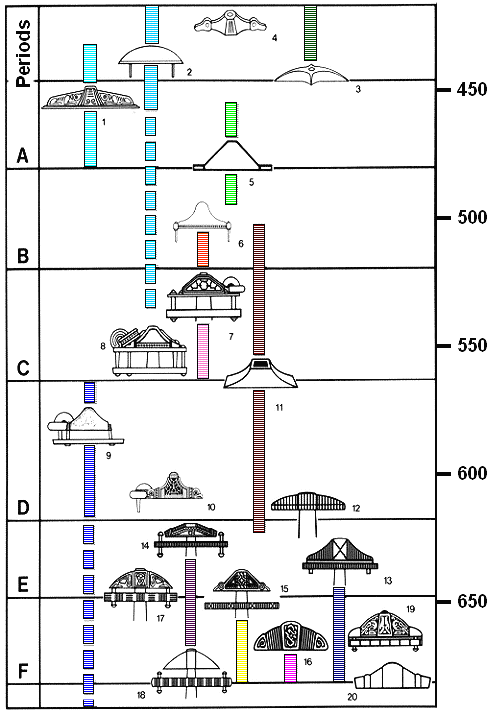

The 9 migration sword subgroups of Behmer

Large picture |

| Source: Some Polish sword site; can't give details, sorry. |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Congratulations to whoever compiled this picture! Scaling and combining the important pictures with Behmer's

often long-winded prose in a meaningful way is a lot of work. As far as I'm concerned, I will only look at one topic in

what follows: |

|

I'll skip the subgroups 7 - 9. They are more or less a transition from

the "fancy hilt" group 6 to the "Viking sword" that has its own backbone

chapter. For the remainder of this module we look into the fascinating if somewhat decadent subgroup 6. |

| |

| |

| | |

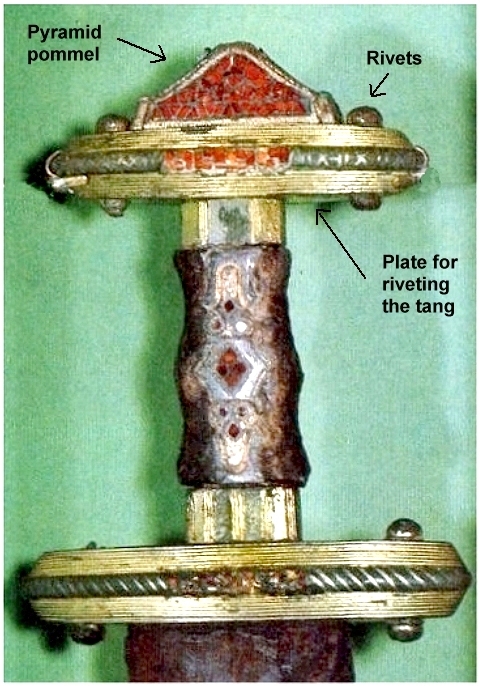

The Pyramid Pommel |

|

The general topic that triggered this module is: "Evolution

of Pattern Welding"; we may also call that: "How Pattern Welding Matured and Died". That development

might well be symbolized with the well-known "pyramid pommel" often associated with the Merovingians

and the Vendel culture. This statement needs to be

qualified in what follows, but first let's look at the object thus described |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

These pommels are typically made from precious metals, often inlaid with (then very precious)

almandine (a garnet variety, mostly red but other

colors do also exist). They are flimsy and neither well suited for fixing rivets nor for bashing heads in. They are prominent

in Wilfried Menghin

book "Das Schwert im frühen Mittelalter"

(Swords during the Early Middle Age) from 1982. |

|

We have a peculiar pommel shape, more or less reminiscent of

a pyramid or actually more of a bicorn hat or cocked hat (the kind Napoleon and Lord Nelson liked to wear). Pyramid pommels

also come with a ring attached to one side as shown above. In Behmer's systematic they belong to the large group B,

subgroup 5. In less well preserved specimen we see a lot of rivets, one rivet is quite prominent in the right-hand

side hilt above.

The first question to consider now is: what are pommels for?

Here is the list: - It serves as a solid endpiece

on which the end of the tang can be securely fastened by riveting, i.e. by hammering it flat. Riveting the tang in

this way fixes all the pieces forming the hilt - at the minimum cross-guard, grip and pommel - securely to the blade.

- It provides the necessary weight needed to balance the sword.

- It serves as decorative element, signaling the wealth / importance of the sword

owner.

- It bears insignia (e.g. a cross) that signals membership to certain groups (e.g.

a " T" for Templer).

- It supplies a bit of magic , e.g. by enclosing relics, being engraved with symbols

or runes, or by other means. Suffice it to mention "sword pearls" in this context.

- It keeps the hand from slipping. That is quite important if you thrust down, e.g.

from horseback.

|

|

|

Quite a list! If you now look at the sword hilts in the picture

above, you see:

- Hilts belonging to Behmer's subgroups 1, 2 and 5 essentially incorporate points 1 and 6 of the

list above, with a bit of point 3. Points 2, 4 and 5 are absent. As far as decorative functions are concerned, the pommel

is not much different from the rest.

- Eastern swords (Behmer's subgroup 4) are not contained in this system. Their tang is short and does not extend

all the way to the pommel. Only the grip is fixed to the tang (I'm not sure how) and the pommel is kind of "nailed"

to the wood forming the grip.

- Subgroup 5 is different. Points 1 and 2 are pretty much missing but points 3 - 6 are very pronounced. Of course,

the tang is still riveted to a part of the many pieces forming the pommel now but that is done in an invisible way "inside"

the whole construction.

Let's look at few pictures to illustrate this. |

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

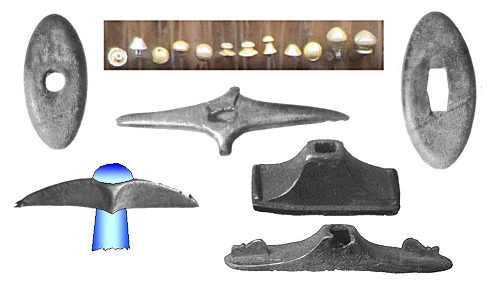

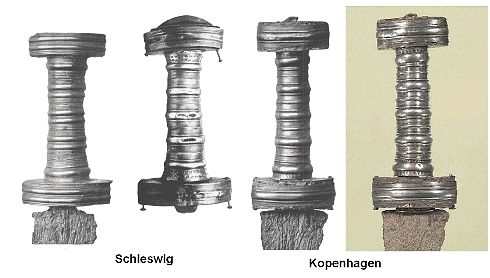

Those pommels from Behmer's subgroup 1 or from even older times do not supply any substantial

weight (they are made from wood, bone or ivory). They certainly prevent your hand from sliding off and they do provide enough

material for securely riveting the tang, always with some metal piece (a rivet plate or cap) right on the bone / wood. Here

are some rivet plates and caps: |

| |

| |

| | |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The two on the lower right-hand side are special: they have a pyramidal shape and belong to

early "subgroup 6" swords.

As long as you use these pommel endpieces for riveting the tang by banging

it (cold) into a mushroom shape, these pieces needed to be made from solid steel and thus could not be particularly decorative. |

|

The next thing that happens (if we dare to put this into a time-line) was that

somebody had a brain-wave and figured out that you can actually rivet your tang to a simple piece of metal like the elliptical

ones above, and then put a fancy kind of endpiece on the whole thing, fastened with rivets to the metal plate. The tang

wouldn't show any more and you could make (the end piece of ) your pommel as flimsy and decorative as you liked. For reasons

of symmetry you used a similar construction for the cross-guard part. Now you could produce a hilt that was more precious

than the blade and really announced the status of its bearer: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

You either used gold inlaid with almandine or at least silver or bronze parts, more or less

fancily decorated . |

|

"Fancy pommel" science got a mighty kick in 2009 when the so-called

"Staffordshire hoard" was discovered in England. It consists of about

3,500 precious items that are mostly related to weapon decoration (nothing for females in there). Most everything dates

to 600 AD - 700 AD; a few early pieces go back to about 530 AD, the youngest ones are from 700+. The items must have been

intentionally damaged, if only by prying them off by force from a hilt.

Why should one have damaged and buried extremely

precious objects around 600 AD in England? We know that the English are notoriously a bit on the weird side but this is

wasting money and that's usually where normal weirdness stops. A few lines from "Beowulf" might point in the right directions: |

| |

Then the one warrior plundered the other,

Stripping Ongentheow of his iron

mail-coat,

His hard-edged hilted sword, and his helm,

Carrying the old man’s armour to Hygelac,

Who

accepted the spoils, and pledged fairly,

To share the rewards, and promptly did so: |

| |

Later it continues: |

| |

They gave to earth the heroes’ treasure,

Gold under gravel, where

it lies still,

And as useless, now, to mankind as ever. |

| |

So we had looting and burial of treasure. The latter, however, in connection with

the burial of a hero and not "just so". |

|

|

Among the items were 86 "pyramid" pommels; 64 made from gold; the rest silver (17) and bronze

(5). 17 of the gold pommels were inlaid with garnets in the cloisonné technique (look it up yourself), the rest were

heavily ornamented. But only one sported a ring! (see below). Compare that to the 29 pommels collected from a huge area

around Uppåkra, Sweden, and the 5 pommels from the Snösbäck / Sveden ritual deposit. There are many single

stray finds, of course, and we have about 400 pyramid pommels altogether. But with 86 pommels from one

place (plus all the other objects) there is now plenty of material to study in a known context. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Some pommel end pieces from the Staffordshire hoard

Large picture |

| Source: Medievalists.net – March 19, 2014 |

|

Details of Staffordshire pommels

Large picture |

| Source: Internet at large (British museum, Birmingham museum, National Geographic, Current

Archaeology, newspapers, ...) |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Occasionally, such a pommel comes up in the antiquity trade so you can buy and actually own one. The link shows an example |

|

There is more to these expensive masterpieces of early medieval gold-smithing

than meets the eye. The surface of the gold below the garnet is often textured into a regular pattern of little pyramids

that reflect the light back - just like the reflectors of your bicycle. This can be seen in the picture below or in the

lower left pommel of the picture here. |

| |

| |

| |

| | The textured gold beneath the garnets |

| Source: National Geographic |

|

| |

|

|

|

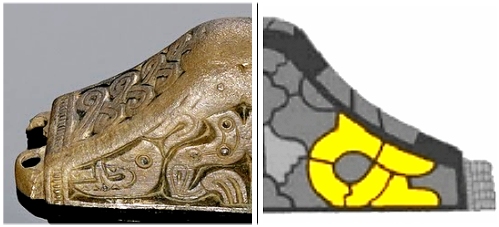

Then, following point 5 from above, the fancy pommel may

well have some magical / spiritual function, in more than one way. The shape of the gold cells inlaid with garnets, or the

decorations otherwise employed, are not always random. They may have meanings: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

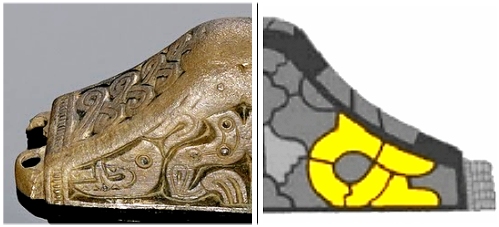

| Front and back of the Hög Edsten Pommelcap |

Source: The Thegns of Mercia; UK Midlands-based group dedicated to exploring Anglo-Saxon

and 'Viking-Age' history. Sth711: Woden's Pommelcap. © Birmingham museum

That's what the source given had to say about this pommel. The actual

pommel, however, is on display in the Stockholm archaeological museum. |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The design on front and back is subtly different. The marked parts designate a boars

head. Yes; I don't see it either but people familiar with early medieval iconography are sure about things like

that. Maybe this picture helps: |

| |

| |

| |

|

A real boars head on a Staffordshire hoard pommel juxtaposed

to its stylized counterpart |

| Source left: The Thegns of Mercia; UK Midlands-based group dedicated to exploring Anglo-Saxon

and 'Viking-Age' history. © Birmingham museum |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Boars are associated with the prominent Norse God Freyr who gets around by

riding the shining dwarf-made boar Gullinbursti. Depictions of boars heads on the pommel might have given protection by

magic.

Here is another pommel with garnets on one side and a kind of Celtic braid in

gold on the other side. |

|

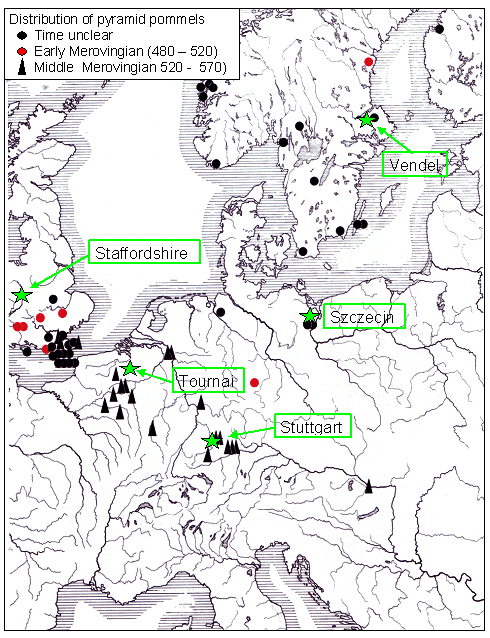

Wilfried Menghin has a lot to say about pommels in general and pyramid pommels

in particular. His book is where you look for details.

Since it is from 1982, it does not contain the Stafforshire hoard and is thus already a bit outdated. It does still contain

a lot of detailed information, though, that is of interest here. For example many maps of where specific things have been

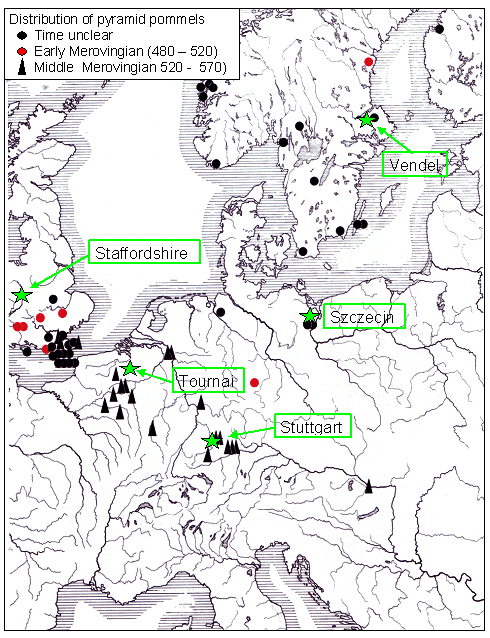

found; here is an example for pyramid pommels: |

| | |

|

|

|

| | Map of pyramid pommel distribution |

| Source Slighlty modified from Menghin's book |

|

| |

| |

|

|

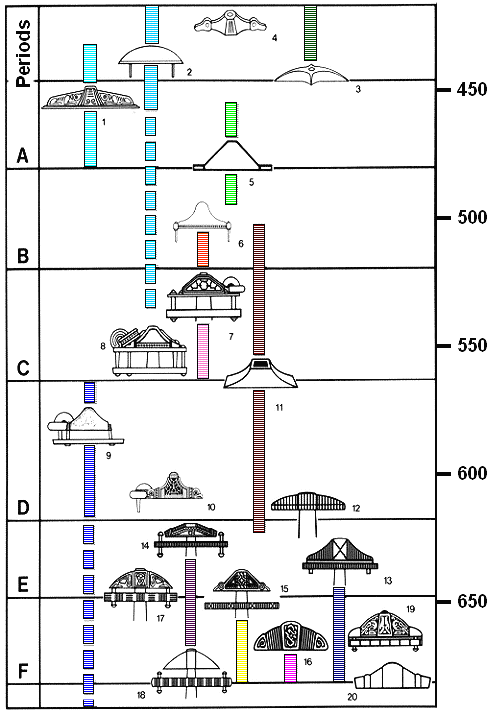

Menghin also gives timelines for specific shapes: Pyramid pommel shapes and time of occurrence |

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

Pyramid pommel shapes and time of occurrence |

| Source Modified from Menghin's book |

|

| |

| |

|

Fancy pyramid pommels thus appeared around 550 AD - just about the time when the

Merovigian and Vendel periods started. That

is why these fancy hilts are often associated with these cultures. |

| | |

|

| |

The Pommel Ring Puzzle |

|

Now you are prepared to appreciate the "pommel ring puzzle

". Some of these hilts come with a ring attached to one side; see above. The puzzle is simple: Why?

The answer is simple, too: We don't really know! |

| |

|

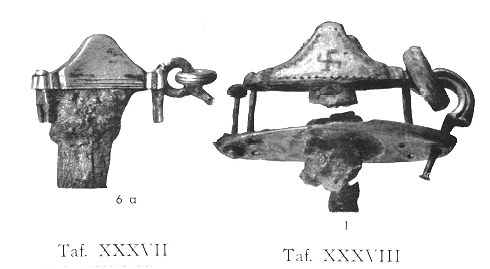

We have some idea how this "pommel ring" developed. Some people call

it "ring pommel" but that will lead to a mix-up with the those swords where the

whole pommel is a ring.

In the beginning,

it seems, somebody just used one of the rivets to make a little loop, enclosing a freely moveable ring. Also note the magical sign on one pommel. |

| | |

|

|

|

| | Simple pyramid shape pommels with rings |

| Source: Behmer |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Later an extra rivet was used for the ring holder and the rings got more massive. They were

often made from gold or silver or at least from bronze, possibly gilded. The rings are more massive and do not move easily

anymore |

| |

| |

| |

|

Merovingian spatha sporting a pommel with ring; found in Dizier, France

Two more pommel ring hilts |

| Source: From Olga Stroganova's web site on "Pin It" |

|

| Pyramid pommel end with two kinds of garnets and unmovable gold ring |

| Source: Sword Forum; Kirk Spencer; unclear origin |

|

| |

| |

|

|

In the end - around 700 AD - the "rings" aren't even separate pieces anymore but

made from one piece of gold or gilded silver / bronze: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| Vendel hilt; Valstenarum; Valstenarum find; Historiska museet Stockholm |

| Source: From Olga Stroganova's web site on "Pin It". Photograph courtesy of

M.Bunker |

|

| |

| |

|

This example gives us a weak clue to what rings were good for. The massive ring

on this hilt was added some time after the hilt had been made. Pieces of the wonderful

gold - almandine work had to be cut off and damaged to make place for the ring. There is evidence that this has happened

with other hilts, too. There is also evidence that a ring was sometimes also removed

from a hilt.

So it appears that some sword owner on occasion felt compelled to add a ring to his pommel, which might

have been removed again somewhat later. Either by the owner or by whoever took over the sword. Now consider that there were

far more fancy-hilt swords without a ring than with one, and you can start to develop your own answer to the "why are

there rings" question. Here are some answers from the literature: |

|

|

Behmer already discussed these suggestions:

- The ring held a strap used to tie the sword to the scabbard. This is obviously wrong considering that many "rings"

weren't hollow anymore, see above. And the riveted loop or eyelet would have been sufficient for doing this anyway, no additional

rings would have been needed.

- The ring assembly served as counterweight to balance the blade. That could have been done in simpler ways, not to mention

that it wasn't efficient.

- The ring assembly just was an ornament. The opposite is true. The effect of the expensive and elaborate ornamentation

already there was destroyed. The hilt above would look better without the ring.

- The ring supplied some magic. Well - maybe. But why was it then removed on occasion? And why did not every hilt sport

a magic ring? If you had the means to acquire a gold - garnet assembly, you certainly could have procured a magic ring,

too.

That does not get us very far. So let's look at newer propositions:

- The ring is connected to the "peace band". Peace bands are mentioned in Viking

sagas and supposedly were tied around the handle of the sword, securing it in place in the scabbard. Untying the peace band

then would have been akin to a challenge to a duel or declaring war. That hypothesis is just a variant of No 1 above and

very unlikely for the reasons given there. It is far more likely that the peace band thing would have looked like this:

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Sword secured with a peace band and adorned with (reconstructed)

"sword pyramids" |

| Source: The Thegns of Mercia; UK Midlands-based group dedicated to exploring Anglo-Saxon

and 'Viking-Age' history. The Anglo-Saxon Sword riddles |

|

| Sword pyramid from the Staffordshire hoard |

| Source left: The Thegns of Mercia; UK Midlands-based group dedicated to exploring Anglo-Saxon

and 'Viking-Age' history. The Anglo-Saxon Sword riddles. © Birmingham museum |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Securing a sword with a peace band as shown also explains in a rather natural way the function

of all those "sword pyramids" or other adornments that have been discovered in a number of Anglo-Saxon graves,

lying beside sword scabbards. From the way they are constructed they were obviously meant to be attached to a strap of some

kind.

But let's go on hypothesizing:

- The rings advertises membership to some formal or informal warrior club, like the "club of Nobel prize winners"

or the "club of warriors who saved the live of their boss" or the club of the "bearers of the Golden Honor

Needle of the Kiel University" (guess who belongs to that club). The ring assembly then was awarded by some leader

to a special person. It was just like receiving a medal today.

- The rings are "oath rings" symbolizing the linking of persons, just like wedding or engagement rings. You

put "the ring" on your pommel after you swore eternal allegiance to your leader. You removed it after you stabbed

him in the back.

That seems to be the best explanation to me. |

|

Enough. We simply don't know the exact function of the pommels with rings for

for sure. But more and more people (including researchers) employ themselves to solving the riddles of iron steel and swords

and new insights are certain to be made in the near future. |

| | |

|

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)