|

Metallography of 8th / 9th Century Swords and Saxes |

|

The Saxes |

|

What follows is essentially an excerpt of Erik Szameit's

and Mathias Mehofer's paper entitled (translated to English) "Technological Investigations

of Early Medieval Weapons from Upper Austria"1). All the pictures in what

follows are (somewhat edited) pictures from this quite interesting publication in an obscure journal.

The guys investigated

these weapons in some detail: |

| | |

|

| |

|

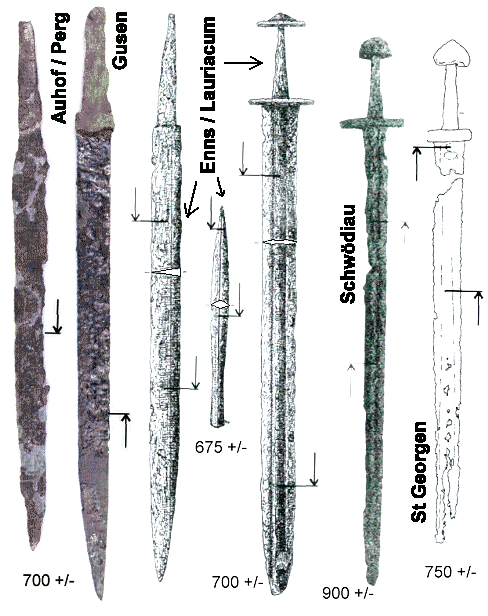

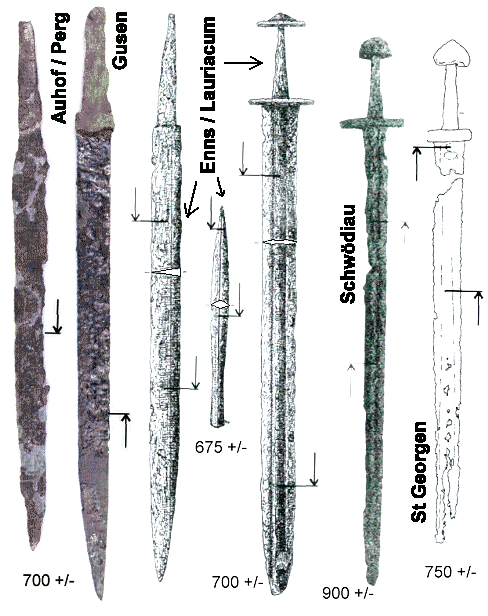

| The weapons investigated. 3 Saxes, 3 swords, 1 lance point |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

It's a long paper with many pictures. Unfortunately the authors did not look

into faggoting and confuse the issue considerably by invoking "carburization"

during the forging many times.

I will only give you the highlights, and I will add my own interpretations of the pictures. |

|

First some data about the saxes: |

|

|

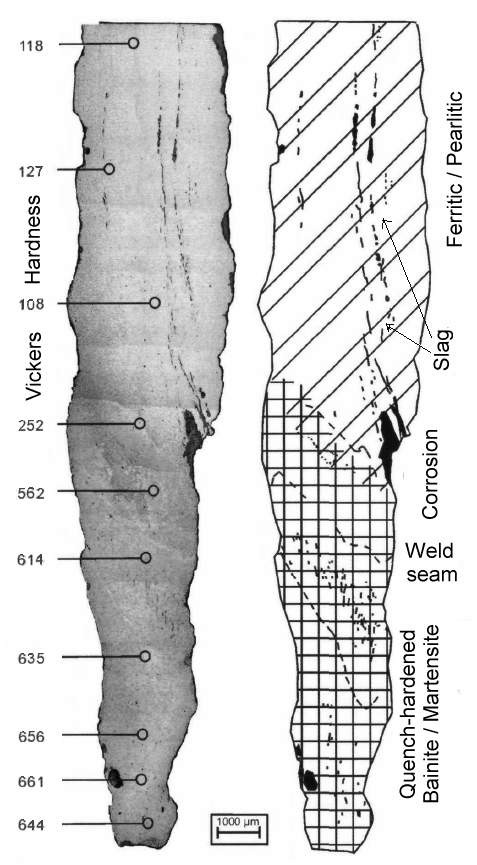

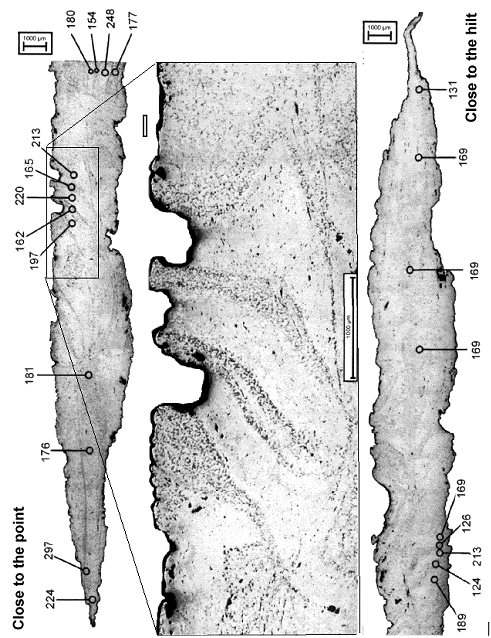

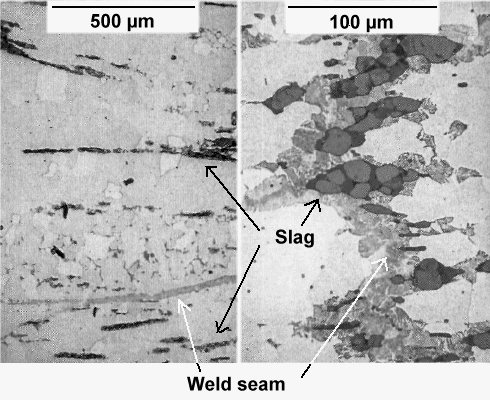

Auhof sax (see below): Several slag bands, possibly from

a few foldings. Otherwise not much slag inclusions in in the bulk. High carbon steel for the edges was joined with low carbon

steel for the bulk. Microstructure and hardness values indicate successful quench hardening of only the edge parts to extreme

hardness values. The weld seam is a bit strange and I don't know what to make of it except to point out once more that fire

welding is a difficult process, especially if you can't easily get up

to 1200 oC (2192 oF) in your forge hearth, as we assume was the case in days of yore.

This sax

is quite comparable to Japanese swords and seems to be similar to the sax from approximately the same time span investigated

in some detail by Stefan Maeder . |

| |

|

|

|

|

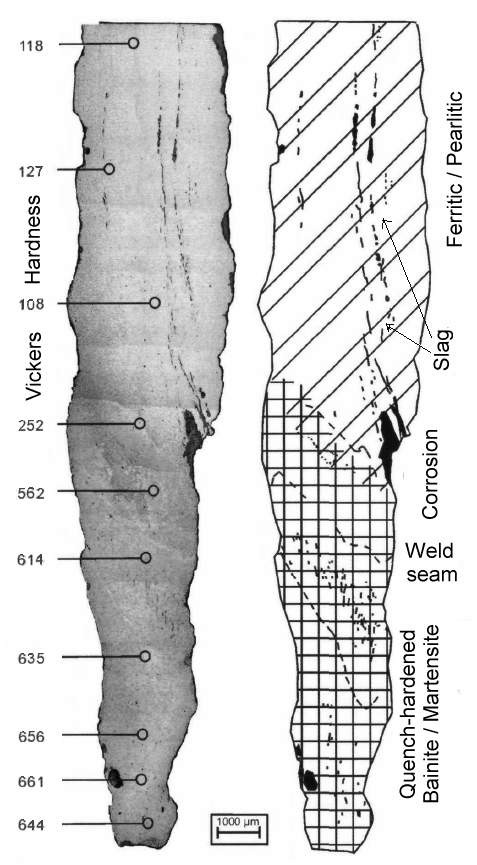

| Etched cross section and schematic structure of Auhof sax |

|

| |

|

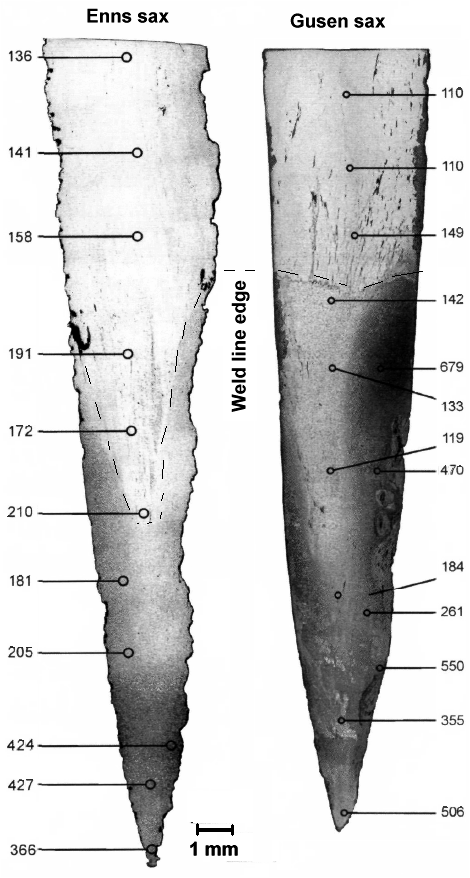

| | Weld seam of edge part and slag inclusions

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

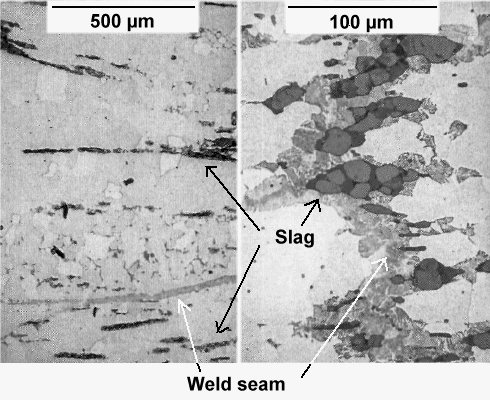

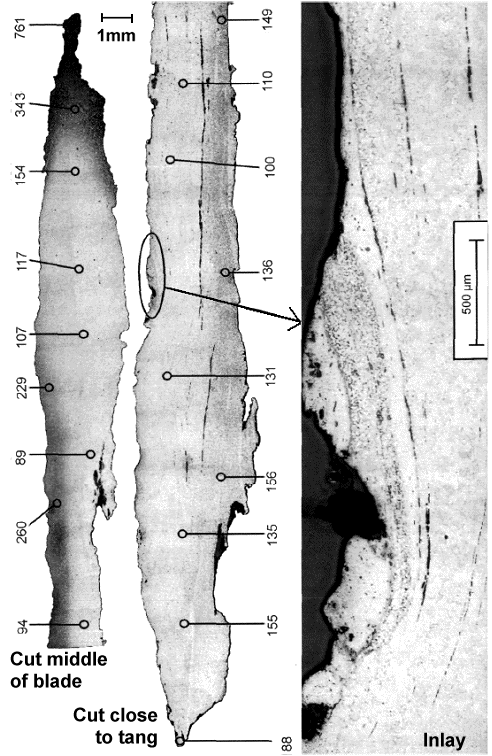

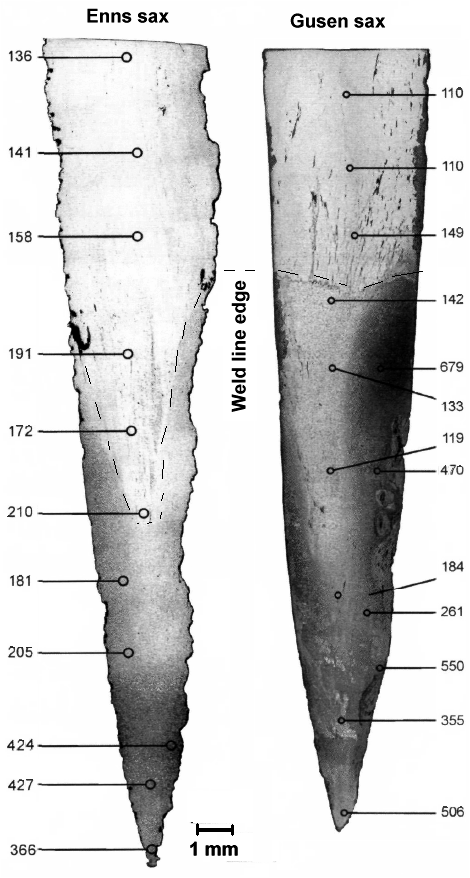

Gusen and Enns sax: The pictures tell it all. The construction

is similar to the sax above. We have a rather well constructed weapons even so the steel is a bit on the slag-rich side: |

| |

| |

| |

|

| Etched cross section and schematic structure of Enns and Gusen sax |

|

| |

| |

|

|

It is clear that those Austrian smiths and / or their suppliers knew how to select proper

grades of carbon steel and how to tell phosphorous steel from carbon steel. The smiths knew a lot about quench hardening

and most likely about faggoting, even so we cannot deduce this from the investigations shown here. If they used differential

hardening by protecting parts of the blade from cooling too rapidly, i.e. by coating it with mud, cannot be told from the pictures here either. |

| |

| |

|

The Swords / Spatha |

|

Now to the swords. First the relatively well preserved pattern welded sword from

Enns / Lauriacum, from the same burial that also yielded the sax and the lance point. Here is what one gets in about half of a cross-section: |

| |

| |

| |

|

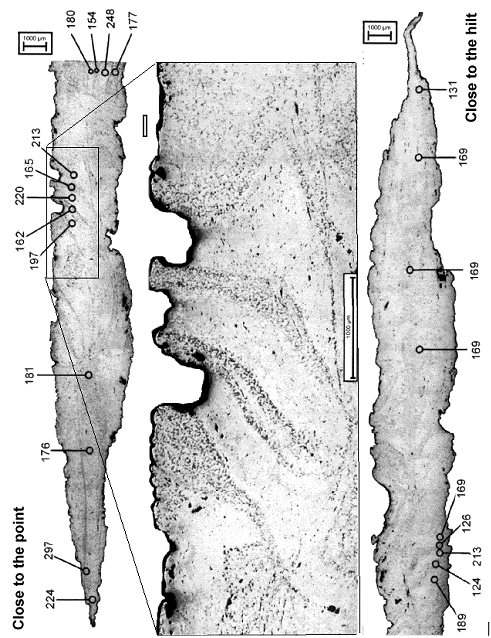

| Etched cross-sections of the pattern welded sword from Enns/Lauriacum |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

A twisted rod texture is visible in the center. The contrast is supposed to result from a

combination of ferritic / ferritic-pearlitic steel (i.e. low and medium carbon) but I'm pretty sure that phosphorous was

involved (the term "phosphorous" was never mentioned by the authors).

It appears that just four twisted rods

are used for the center of the blade as opposed to four one each side as would be required for the inferred pattern with

the typical curlicues only obtainable if the rods are ground down a lot.

Whatever. While the blade might have sported

a nice pattern, it was inferior to its sax companion in terms of hardness. Nevertheless, an attempt to have a hard edge

was made, and we might simply have lost the real hard edge to corrosion. |

|

The two remaining swords are not pattern welded but piled without a pattern (edges

hard steel, inside softer steel). They are quite interesting because both of them contain remains of a simple inscription that was obtained by hammering a small striped rod into the blade. Here is

the one of the St. Georgen spatha: |

| |

| |

| | |

|

| Two "O" shaped inlays of striped rods in the blade |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

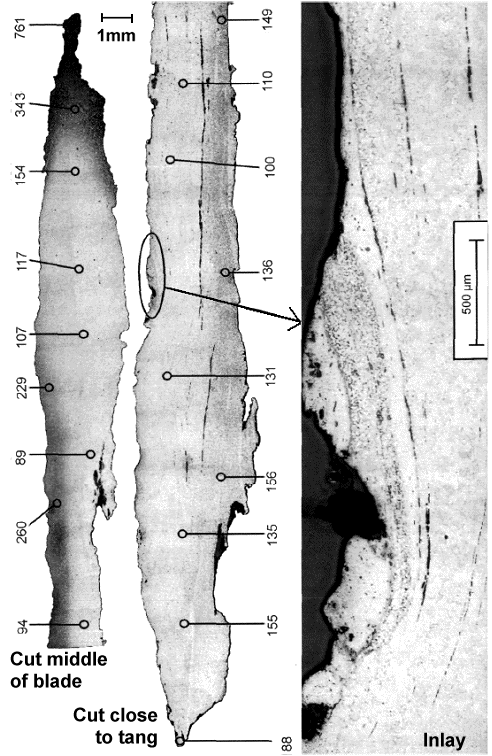

Here is a partial cross-section cutting through the inlay of the St. Georgen spatha: |

| |

| |

| | |

|

| Etched cross-sections of the St. Georgen sword with an inlay |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The Schwödiau spatha looks much the same. One might guess in both cases that the striped

rod "wire" was just hammered in without making a groove first because the slag trails in the bulk just curve around

and are not interrupted. |

|

From the picture above it is clear that quench hardening was applied, producing

an extreme hardness of 761 at the edge of the blade. The body of the blade was quite soft, on the other hand. Again it appears

that the smith knew exactly what he was doing. His raw materials, however could have been a bit better with respect to the

slag content.

The inlays are significant, I think. They take us right to the famous "+VLFBERH+T swords of chapter 11.4. |

| |

| |

| 1) |

Erik Szameit und Mathias Mehofer: "TECHNOLOGISCHE UNTERSUCHUNGEN AN WAFFEN

DES FRÜHMITTELALTERS AUS OBERÖSTERREICH", Jb. Oö. Mus.-Ver. (Oberösterreichischer Musealverein;

if you Non-Germans / Austrians can pronounce that you get a free beer!) ), Bd. 147/1, Linz 2002 |

With frame

With frame

Fire Welding

Fire Welding

Critical Museum Guide: Landesmuseum Württemberg; Württemberg State

Museum, Stuttgart, Germany

Critical Museum Guide: Landesmuseum Württemberg; Württemberg State

Museum, Stuttgart, Germany

Critical Museum Guide: Museums in Copenhagen

Critical Museum Guide: Museums in Copenhagen

Critical Museum Guide: Landesmuseum Schleswig-Holstein in Schleswig, Germany

Critical Museum Guide: Landesmuseum Schleswig-Holstein in Schleswig, Germany

Critical Museum Guide: "The Vikings" Special Exhibition from Oct.

2014 - Jan. 2015 in the Martin-Gropius-Bau

Critical Museum Guide: "The Vikings" Special Exhibition from Oct.

2014 - Jan. 2015 in the Martin-Gropius-Bau

11.4.2 Blades of Viking Era Swords

11.4.2 Blades of Viking Era Swords

Faggoting

Faggoting

11.3.3 Evolution of Pattern Welding

11.3.3 Evolution of Pattern Welding

Radiographie Study of Pattern Welded Swords

Radiographie Study of Pattern Welded Swords

Structure Investigations of Pattern Welded Swords

Structure Investigations of Pattern Welded Swords

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)