| |

|

|

Here are some notes about some of the (early) "Heroes" of Dislocation

Science. It is a purely subjective collection and does not pretend to do justice to the history of the field or the people

involved. I will not even remotely try to establish a "ranking", and that's why names appear in alphabetical order. |

|

To put things in perspective, let's start with a short history of the invention of the dislocation, followed by their actual discovery. |

|

|

Dislocations were invented

long before they were discovered. They came into being in 1934

by hard thinking and not by observation. As ever so often, three people came up with the concept independently and pretty

much at the same time. The three inventors were Egon Orowan, Michael Polanyi and Geoffrey Taylor. What they invented was

the edge dislocation; the general concept of dislocations had to

wait a little longer.

Of course, they all knew a few things that gave them the right idea. They knew about atoms and

crystals since X-ray diffraction was already in place since

1912. They also knew that plastic deformation occurred by slip on special lattice planes if some shear stress was large

enough, and they knew that the stress needed for slip was far lower than what one would need if complete planes would be

slipping on top of each other. |

|

|

They were also aware of the work of others. Guys with big names then and still today, like

T. v. Kármán, Jakow Iljitsch Frenkel, or Ludwig Prandtl, had put considerable effort into theories

dealing, in modern parlor, with the collective movements of atoms in crystals. Markus Heyerhoff, in his PhD thesis from

1997 (University of Greifswald / Germany) has a lot to say about that and the rather fearsome equations that those guys

dealt with.

I must mention Ulrich Dehlinger in this context. Not only was he one of my Professors when I studied physics

in Stuttgart / Germany, he almost "invented" the dislocation in 1929.

|

|

|

This is a know phenomena in science. For every big breakthrough linked to one name (e.g. Albert

Einstein) there are always some precursors that almost did it. For Einstein's special

relativity theory, for example, we have Poincaré and Lorentz, rather well-known scientists then and now. Another

known phenomena is that the acknowledged heroes usually didn't get it quite right or did not address important parts. For

Einstein's special relativity theory once more, it was Minkowski who introduced the extremely innovative and elegant four-dimensional

"space-time" concept that makes Einstein's stuff so much more powerful.

We have the same thing here. While

all the dislocation inventors supplied a drawing that shows a recognizable edge-dislocation (see below), some of their stuff

is questionable or incomplete. |

|

|

Another known phenomena in science is that some mathematician or theoretician, for some obscure

reason of his own, had already produced some framework for the big discovery yet to be made. In the case of dislocations

it was Vito Volterra, who in 1905 provided just about everything needed to invent the dislocation. |

|

|

The last known phenomena in science is that some others, always including a least one major

celebrity, bitterly oppose the new "invention" or insight. In the case of the dislocation, it was, for example,

famous Frenkel. A more recent example can be found in this

link. |

|

Nevertheless, the break-through made in 1934 was recognized by others, and the

floodgates opened up for a deluge of research into dislocation science. New and important discoveries were made by many

in a short time. I will only mention some of that, mostly because I don't know the details, and also because it would get

too special and technical. |

|

|

Playing merrily with the new toy was spoiled on two points, however:

- The Nazis and the war made life difficult for many researchers in Germany and elsewhere. A lot were forced to emigrate,

including Polanyi and Orowan. The rest couldn't do whatever they liked either. On the other hand, war-time necessities included

improved metal techniques, and this lead to some special research that furthered the cause, e.g. in the context of the Liberty Ships.

- Nobody has ever seen a dislocation until 1955 / 56. To be sure, there was more and more experimental evidence, mostly

from defect etching or similar techniques, that left no doubt

that the concept was sound - but only seeing is believing!

|

|

|

The first direct observation of a dislocation in a transmission

electron microscope was thus of great importance. It also opened up the road to present-day micro- and nanotechnologies

with an ever increasing arsenal of sophisticated analytical techniques. |

|

Some more details will be given in the short portraits that follow. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

Everybody who knows the least thing about dislocations knows about the "Burgers vector" of dislocations. The Dutch scientist

J.M. Burgers came up with this simple and powerful way to describe the "strength" and type of a dislocation.

| |

|

Johannes (Jan) Martinus Burgers

* January 13, 1895, Arnhem, Netherlands

† June 7, 1981, Washington D.C. |

| Source: Wikipedia |

|

|

|

He also is the "inventor" of the screw dislocation concept. Moreover, he was the first one to

describe low-angle grain boundaries in terms of dislocation

arrays.

His seminal contributions were published in 1939 in the "Proceedings of the Royal Soc. of Sciences"

(Amsterdam).

In 1940 he published an influential summary of the state of the "dislocation" art in the Proceedings

of the Physical Soc. in London. | |

|

|

It may thus come as a surprise (it certainly surprised me) that Jan Burgers was actually an

authority on fluid dynamics for most of his life. He was dragged into the emerging dislocations science by his younger brother

Wilhelm Gerard Burgers, a well-known metallurgist in his

time, especially for his work about recrystallization. | |

| |

|

It seems that the curls or eddies in fluids, entities well-known to Jan Burgers, inspired

him to come up with the dislocation stuff that made him immortal for a long time to come. He was also the more mathematically

inclined and more experienced of the two brothers at this time. After he made his contributions, he went back to fluid dynamics

and never looked back. | |

| |

|

And now you also know why dislocations have a Burgers vector and not a Burger's vector. |

|

References:

Burgers, J, M., Proc. K. Akad. Wet. Amst., 42 (1939), p.

293 and 378 (2 contributions)

Burgers, J. M., "Geometrical considerations concerning the the structural irregularities

to be assumed in a crystal", Proc. Phys. Soc. (London) 52 (1940) 23-33

Burgers, J. M., "How my brother and

I became interested in dislocations", Proc. Phys. Soc. (London) A 371 (1980) 125-130

Parts of the content here

comes from the excellent book of E.J. Mittemeijer.

|

| | |

|

| |

|

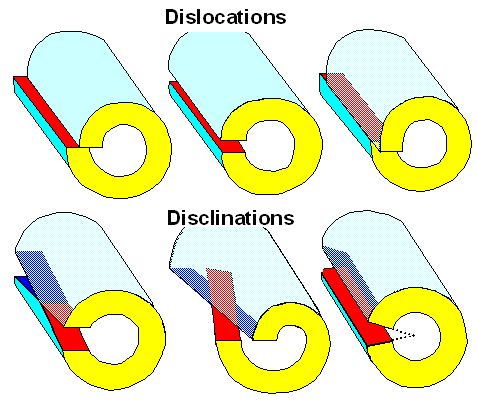

Prof. Dr. Ulrich Dehlinger was one of my academic teachers in Stuttgart. He was

an "original", noted for his many intentional and unintentional quips and wisecracks that invariably came up during

his lecture courses. He was also feared by us undergraduates because the examination for his (required) "Technische

Mechanik" lecture course was hard to pass. | |

| Ulrich Dehlinger

* June 6th, 1901; Ulm, Germany

† June 29th, 1981, Stuttgart, Germany |

|

|

|

Many years later I realized that his wisecracks, that we thought to be a bit

offbeat and funny, were actually full of wisdom. After I became a professor myself, I also realized that with his fearful

exams he was simply doing what was needed: weeding out the students not fit for the demanding study course rather early,

saving them and himself the pain of having to drag them along to an unsuccessful ending later.

The picture shows him

going at full throttle in 1976, his last year of active teaching. | |

|

|

U. Dehlinger studied physics in Tübingen, München and Stuttgart, finishing with

the degree of "Dipl.-Ing." in Technical Physics in 1923, and with the then very prestigious Dr.-Ing. in 1925.

In 1929 he applied for a "habilitation", a kind of second Dr. degree, necessary and qualifying for a professorship

in Germany. In 1939 he became an "Ordinarius" (full professor) for Theoretical Physics at the "Technische

Hochschule Stuttgart"; later University Stuttgart. . | |

| |

|

In the scientific work for this advanced degree he introduced the concept of "Verhakungen",

a German construct that cannot be properly translated. It means something like "hooked together things" or "hookings".

Dehlinger was a theoretician, albeit a practical one. It is important to realize that his "Verhakungen" were not

a qualitative concept, just sketching possible crystal structures that might work in explaining something, but results of

rather complex math applied to the problem of how whole collections of atoms could move in periodic structures like crystals.

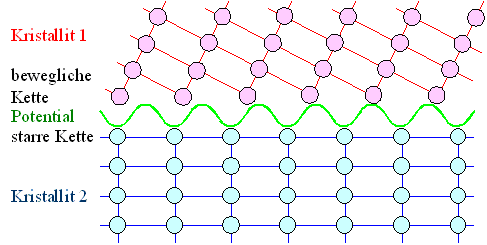

He enlarged on a concept earlier proposed by Prandtl, who considered

what happens to the atoms in between two perfect crystalline regions with somewhat different orientations (a (small angle)

grain boundary in modern terms). They would experience a periodic potential and, as Prandtl showed more or less qualitatively,

could explain permanent deformations at low stress. Prandtl came close to the concept of imperfections or defects in crystals

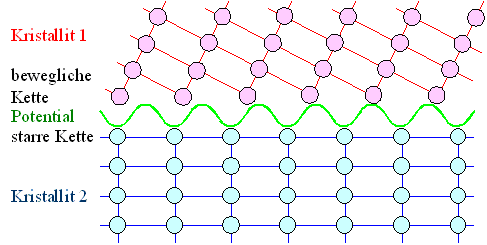

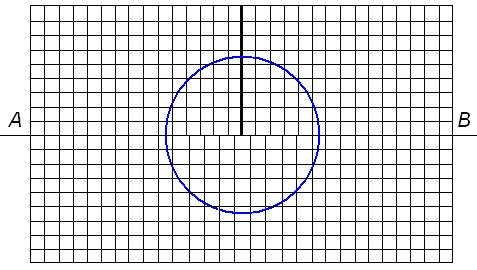

but did not get quite there. Here is the key picture oft Prandtl's model (redrawn and color added by me): |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

Prandtl's Model

(Bewegliche Kette=Movable chain, starre Kette=fixed chain) |

| Sources |

|

| | |

|

|

Dehlinger, however, developed his model independently. He only became aware of

Prandtl's work (which he acknowledged) after he had worked out his own ideas. |

|

|

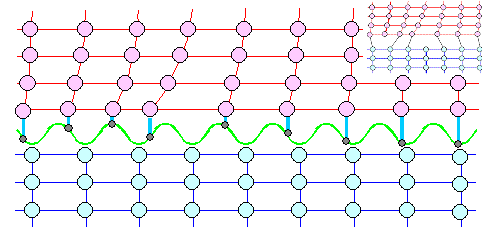

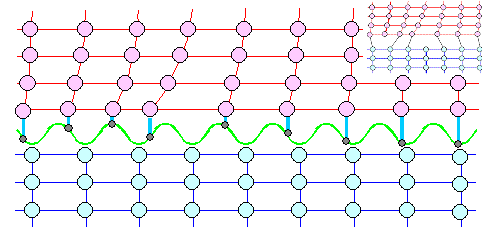

In contrast to Prandtl he considered the two crystallites being of the same orientation

and worked out the details in complex and rigorous math. Here is his key picture of a "Verhakung" (redrawn and

color added by me): |

| |

| |

| |

| Dehlinger' Verhakung

|

|

| | |

|

|

|

The green line shows the periodic potential used, and the blue lines indicate

the energy of the atoms in the "Verhakung".

Not yet an edge dislocation but getting there. One could interpret

this contraption as an edge dislocation dipole as shown in the inset but that wouldn't do justice to Dehlinger's intentions. |

|

References:

Ulrich Dehlinger: Zur Theorie der Rekristallisation reiner

Metalle. Habilitationsarbeit. Annalen der Physik (5) 2 (1929) 749-793. |

| | |

|

| |

|

When I worked the electron microscopes around 1975 in in A. Seeger's big Max-Planck

Institute in Stuttgart, I knew Sir Peter the same way I knew the Pope. Well, Sir Peter, never seen in person by us little

people, was the Pope as far as electron microscopy was concerned. Our own Boss, in this kind of idolatry, then was Martin

Luther, challenging the Pope to the best of his ability but not really getting him down. |

|

|

Sir Peter Hirsch

* 16 January 1925 |

|

|

|

Hirsch's book about electron microscopy was (and to some extent still is) the

Bible. | |

|

|

In 1946 Hirsch (not yet Sir Peter) worked under famous Lawrence Bragg for his PhD in the Crystallography

Department of the Cavendish. In the mid-fifities he pioneered the application of transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

and developed in detail the theory needed to interpret such images.

In 1966 he moved to Oxford to take up the Isaac

Wolfson Chair in Metallurgy, succeeding William Hume-Rothery. He held this post until his retirement in 1992, building up

the Department of Metallurgy (now the Department of Materials) into a world-renowned centre. |

|

|

It was his group that saw a dislocation for

the first time and knew what they saw. In Dec. 12th, 2002, he was interviewed at length

about the development of Materials Science in the UK and elsewhere. Here are a few interesting quotes (my highlights and additions):

|

| |

|

"By the time we found that cold worked aluminium breaks into subgrains, Heidenreich at the Bell Laboratories published the first

pictures of metals by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). He observed directly the little subgrains in heavily beaten

aluminium foil. That depressed us very much because we needed exposures of many hours for our x-ray diffraction photographs,

while he had a ten second exposure with his electron microscope. So we went into this field of TEM and finally we saw

individual dislocations

for the first time.

This had a big impact because there were many metallurgists

who did not believe in dislocations, who considered them as figments of the imagination of solid state physicists working

out theories in tremendous detail without much supporting experimental evidence. With our technique you could see dislocations

directly and see them move. And we made movies. I remember showing a movie at MIT to Bert Warren who was a well-known X

Ray crystallographer. His comment was symptomatic of many metallurgists. Seeing is believing. We

converted people. |

| | |

Finally would you consider yourself today more as a physicist or as a material scientist?

"I think I am a physicist who «saw the light». True physicists would no longer consider me as

a physicist. I consider myself as a materials scientist because my interest is in the effect of microstructure on the properties

of materials. I am interested in quite complex materials, with potential applications e.g. high temperature intermetallics,

and in modelling their complex mechanical properties. I ended up as a materials scientist. But there are materials scientists

who would consider me to be a rather theoretical materials scientist. In the later years of my conversion I supported and

promoted materials processing in the department although it took me rather a long time to get to this view, to appreciate

the importance of this field, and to realize the need and potential for modelling." |

|

You can read the story of the first dislocation picture in Sir Peter's own words

in this link. To augment this, you can also read about the story from Michales Whelan, Hirsch's colleague and at least as

involved in this as Hirsch.

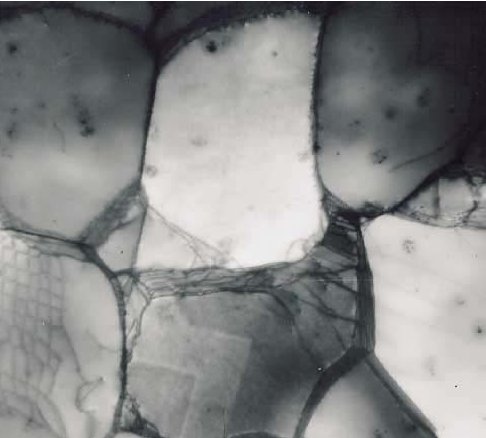

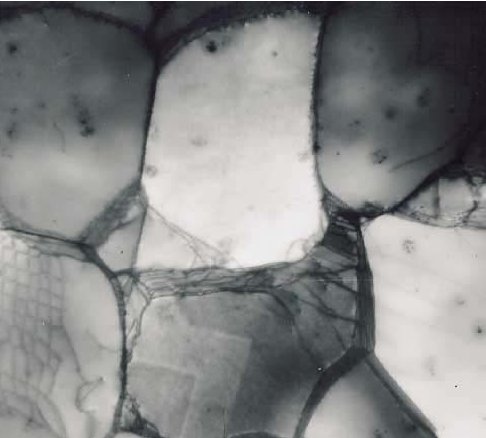

Here is one of those first diffraction contrast pictures showing dislocations taken in a

transmission electron microscope (TEM), a Siemens instrument

at those heroic times: |

| |

|

|

|

|

| First diffraction contrast TEM picture of dislocations |

| Prominent are the grains. The fainter lines, in particular the network on the lower left, are dislocations.

| | Source: Whelan interview |

|

| | |

|

|

References:

P. Hirsch, A. Howie, R.B. Nicholson, D.W. Pashley and M.J.

Whelan "Electron Microscopy of Thin Crystals", written in 1965

P. Hirsch; "50 Years of Transmission Electron

Microscopy of Dislocations: Past, Present, and Future"; Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 2006, Vol. 76, No.

5, pp. 430–436.

Address of interviews: http://authors.library.caltech.edu/5456/1/hrst.mit.edu/hrs/materials/public/Hirsch/Hirsch_interview.htm

http://authors.library.caltech.edu/5456/1/hrst.mit.edu/hrs/materials/public/Whelan/Whelan_interview.htm

|

| | |

|

| |

|

Egon Orován was one of those many famous

Hungarian scientists and artists1) who made the world a different place

in the early 20th century. | |

|

Egon Orowan

* Aug. 2nd, 1902

† Aug. 3rd, 1989 |

| Source: Uni Cambridge. Museum |

|

|

|

Orowan was born around Budapest. He started studying mechanical and electrical

engineering at the Technical University of Berlin in 1928, but soon transferred to physics, completing his doctorate on

the fracture of mica in 1932. | |

|

|

1937 Orowan moved to the University of Birmingham, UK where he worked on the theory of fatigue collaborating with Rudolf

Peierls; in 1939, he moved to the University of Cambridge where he worked with William Lawrence Bragg

| |

|

|

During World War II, he worked on problems of munitions production, particularly that of plastic

flow during rolling. In 1944, he was central to the reappraisal of the causes of the tragic loss of many Liberty ships, identifying the critical issues of the notch sensitivity of poor

quality welds and the aggravating effects of the extreme low temperatures of the North Atlantic. | |

| |

|

n 1950, Orowan moved to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston / USA. He made

many more important contributions to dislocation science, applied fracture theory to geological and glaciological topics,

and finally succumbed to that disease plaguing many elderly scientist (me included) and dabbled in philosophy, economy,

and generally explaining the world at large. | |

| |

|

He used, for example, the writings of some 14th century Tunisian historian Ibn

Khaldun to forecast an eventual failure of markets. His ideas found little acceptance among the majority of economists,

which might have been a mistake, considering that their ideas do no have much punch either (consider the various economic

crises following each other in rapid succession right now). |

|

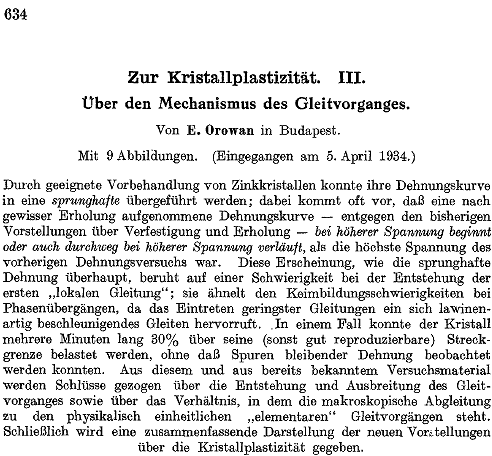

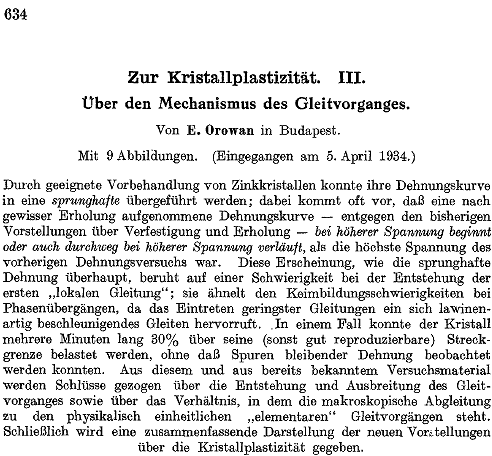

Anyway, here is the front page of his paper: |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

| Orowan's paper |

|

| | |

|

|

|

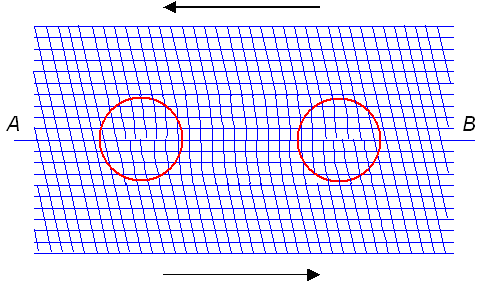

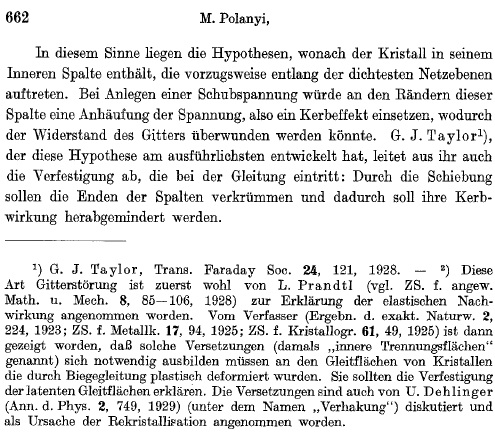

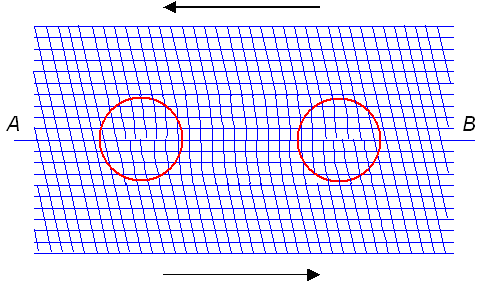

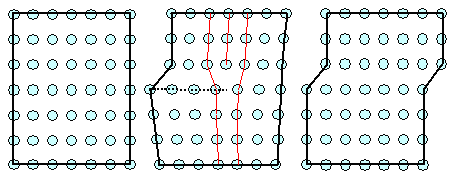

Here are his decisive pictures (redrawn and color added by me): |

| | |

|

|

|

| | Orowan's dislocation |

| Nowadays we would interpret it as a cut through a dislocation loop in a plane where the dislocation

is purely edge type. |

|

| | |

|

|

|

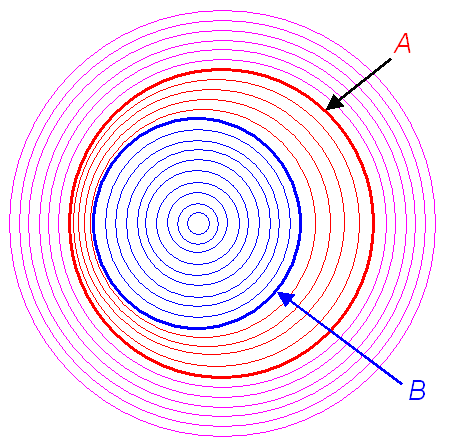

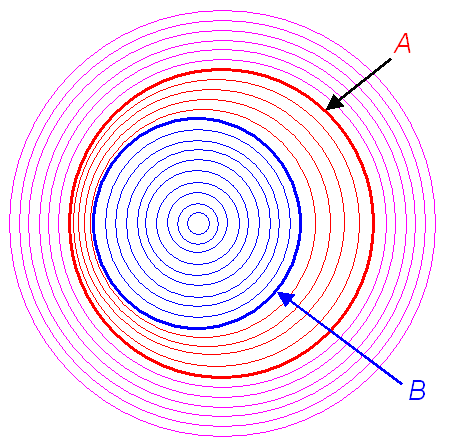

This picture is shown a lot in text books. The next picture, however, I have not

seen before I consulted Orowan's original paper. It shows that Orowan did have a dislocation loop in mind, but didn't get

it quite right because the screw dislocations hadn't

been properly invented yet (even so it was implicitly contained in Volterra's

work). Here is the picture (redrawn and color added by me): |

| |

| |

| |

| | Orowan's dislocation loop |

| The large pinkish circles denote the unchanged part of a crystal below the loop, the blue circles

the slipped and undistorted part on top. The red circles show the distorted part in between |

|

| | |

|

|

|

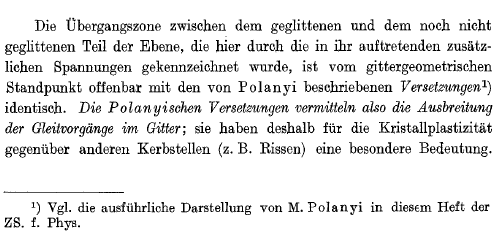

Orowan and Polanyi knew about each others work and actually made sure it was published

together. Here is Orowan's reference to Polanyi: |

| |

| |

| |

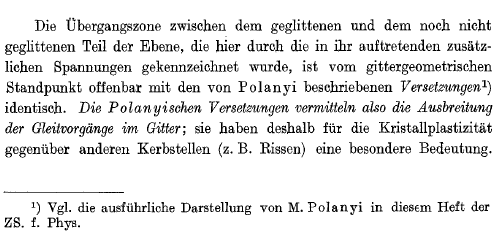

| | Orowan's reference to Polanyi |

| "The transition zone between the glided and unmoved part of the plane, marked here by

the additional stresses, is evidently identical to the dislocation described by P o l a n y i if seen from a lattice

geometry viewpoint." |

|

| | |

|

|

References:

Orowan E. "Zur Kristallplastizität. III. Über

den Mechanismus des Gleitvorganges" (To crystal plasticity III. About the mechanism of glide), Z. Physik, 89

(1934) 634 |

| |

|

| |

|

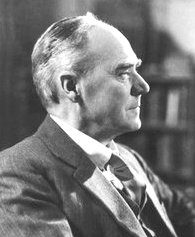

Mihály Polányi was born in Budapest in 1891 and is another member

of those many Hungarian scientists and artists1) who made the world a different

place in the early 20th century. | |

|

Michael Polanyi

* March 11, 1891

† February 22, 1976 |

| Source: Polanyi Society |

|

|

|

After obtaining a medical diploma in 1914, he made it to the Technische Hochschule

in Karlsruhe, Germany, to study chemistry. Peregrinations during the first World-War (as a medical officer) ended with a

doctorate from the University of Budapest in 1919.

After a few more adventurous years he finally became the professorial

head of department of the "Institut für Physikalische Chemie und Elektrochemie" in Karlsruhe.

Forced

out by the Nazis, he moved to the University of Manchester. Two of his pupils, Eugene Wigner

and Melvin Calvin, not to mention his own son, went on to win a Nobel Prize. |

|

|

|

Polanyi's scientific interests were extremely diverse, including work in chemical kinetics,

x-ray diffraction, and the adsorption of gases at solid surfaces. In 1934 he realized that the plastic deformation of ductile

materials could be explained in terms of what we now call a dislocation. | |

|

In later life he became a philosopher, like Orowan. In contrast to Orowan he received

some recognition for this work to this very day. | |

| |

|

Here is his decisive picture (redrawn and color added by me): |

| | |

|

|

|

| | Polanyi's dislocation |

|

| | |

|

|

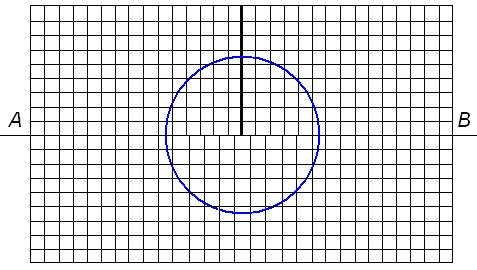

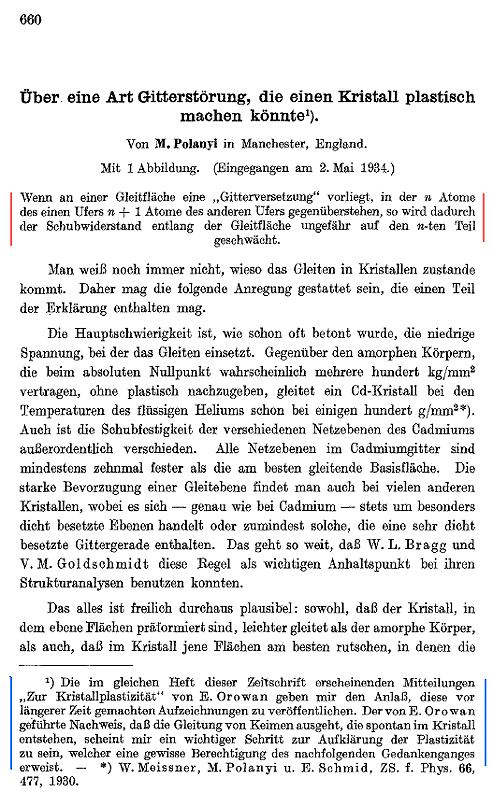

Here is Polanyi's opening page: |

| | |

| |

|

| Polanyi's paper |

|

| | |

|

|

|

The abstract of his paper (red lines) simply states:

"If there is a lattice dislocation in a slip plane, with n atoms on the one coast opposed to n

+ 1 atoms on the other coast, the resistance to shear along the glide plane will be weakened to about 1/n.".

The idea is correct but the statement is not.

The footnote (blue lines) contains his reference

to Orowan. It reads:

"The communication "Zur Kristallplastizität" (to crystal plasticity) of E.

Orowan contained in this volume induced me to publish these notes made some time ago. The proof of E. Orowan, that glide

issues from nuclei spontaneously generated in a crystal, appears to me to be an important step in the elucidation of plasticity,

justifying to some extent the following thoughts. |

|

|

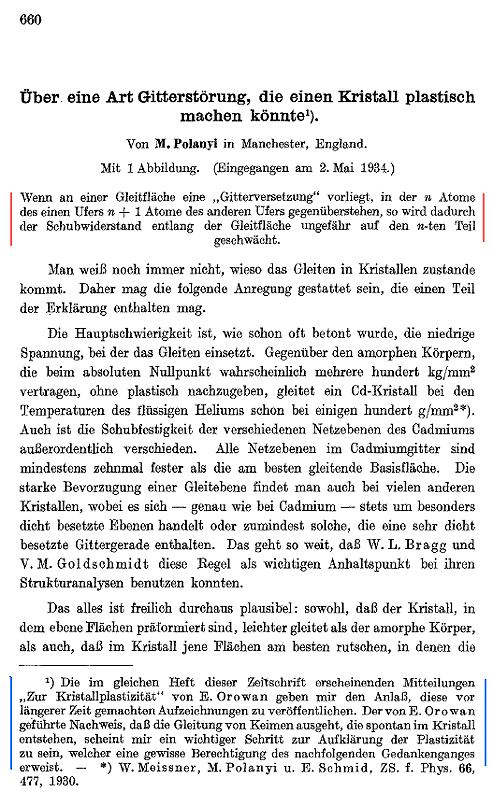

Polanyi also refers to the work of Taylor, Prandtl and Dehlinger: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

|

References:

M. Polanyi, "Über eine Art Gitterstörung,

die einen Kristall plastisch machen könnte" (About a kind of lattice distortion that could render a crystal "plastic"

(=ductile) ), Z. Physik, 89 (1934) 660 |

| |

| |

| |

|

Geoffrey Ingram Taylor (affectionately known as G. I.) was a very British mathematician

and physicist with a focus on hydrodynamics (like Prandtl or Burgers) and made quite a name for himself in that discipline. | |

|

* March 7th. 1886

† Jun 27th 1976 |

|

|

|

During the first World War he was sent to the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough

and did theoretical work, e.g. on the stress on propeller shafts. Not so theoretical, he also earned to fly aeroplanes and

to parachute. | |

|

|

in 1923 he was appointed to a Royal Society research professorship as a Yarrow Research Professor

in Oxford. This enabled him to stop teaching, which he neither liked nor could do very well.

It was in this period

that he did his most wide-ranging work on the mechanics of fluids but also, following up his work at Farnboroug, in solids.

This lead to his "discovery" of the (edge) dislocation in 1934. In 1934. Taylor also realized that the theory

of "dislocations" as developed by Vito Volterra in 1905 was instrumental

for this. | |

| |

|

He did not succumb to the lure of "philosophy" as his two dislocation co-inventors

but had botany as a hobby and sailing as a kind of obsession. Once more he became practical and invented and patented a

special kind of anchor. His final research paper was published in 1969, when he was 83. In it he resumed his interest in

electrical activity in thunderstorms, as jets of conducting liquid motivated by electrical fields |

|

|

Here is his decisive picture (redrawn; color and the red lines added by me): |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

Taylor's (positive) dislocation

The second picture of the "negative dislocation

is essentially the same picture just

standing on its head. |

This looks not only very much like a classical edge dislocation, it also shows how plastic

deformation comes about by the movement of the dislocation.

Here is the text to this picture |

|

|

| | |

|

|

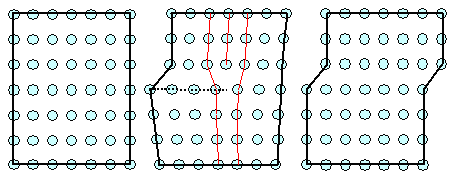

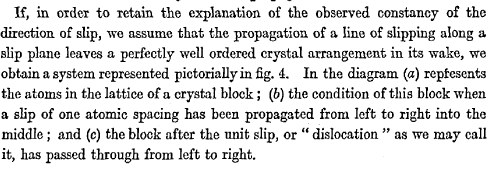

The Royal Society expects, of course, that publications in its august journal

are always read from the beginning to the end and thus supplies no abstract. Instead of the beginning of the article I therefore

show the parts referring to Dehlinger and Volterra: |

| |

| |

| |

|

| | |

|

| |

|

|

| | |

|

|

Taylor's paper - with a part I and a part II - is 53 pages long and goes deep

into theory and math. It certainly would have been sufficient to establish the dislocation once and for all. |

| | |

|

|

References:

G. I. Taylor, "The mechanisms of plastic deformation

of crystals. Part I—Theoretical; Part II—Comparison with Observation; Proc. Royal Soc. Series A, Vol CXLV (=145)

(1934) p. 362 - 415 |

| |

| |

| |

|

Vito Volterra was an Italian mathematician and physicist. He was and is far more

famous for his contributions to mathematical biology and integral equations than to dislocation science.

Born in Ancona,

then part of the Papal States, into a very poor Jewish family, Volterra showed early promise in mathematics before attending

the University of Pisa, where he became professor of rational mechanics in 1883. In 1892, he became professor of mechanics

at the University of Turin and then, in 1900, professor of mathematical physics at the University of Rome La Sapienza. |

|

|

Vito Volterra

* May 3rd, 1860

† Oct. 11th 1940 |

| Source: The Net at large |

|

|

|

In recognition of his scientific achievements, Volterra was made a senator of

the kingdom of Italy in 1905. But in 1931 he was one of only 12 out of 1,250 professors who refused to take a mandatory

oath of loyalty to the fascist regime. As a result, he was compelled to resign his university post and his membership of

scientific academies, and, during the following years, he lived largely abroad, returning to Rome just before his death.

| |

|

|

His work, I read in biographies, is summarized in his book "Theory of functionals and

of Integral and Integro-Differential Equations (1930)"

Indeed, it is hard to find general references to his work relevant for dislocations.

| |

|

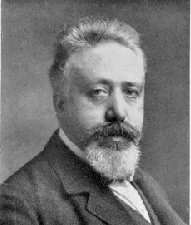

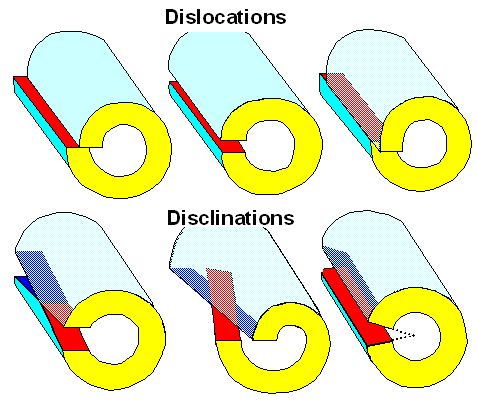

What he did was to propose a new theory of elastic distortions.

On the surface, it is outrageously simple. He took a hollow tube, cut it lengthwise, and considered how you can "glue"

it together again (removing or inserting material if necessary), and what kinds of stress and strain fields would result.

Note that his material was continuous mathematical "brain" matter. There were no atoms and hence no crystals involved.

The six possibilities he came up with are shown in the figure below: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| Volterra's six essential "cut and glue" constructs. |

|

| | |

|

| |

|

If it is not directly obvious to you that this is a work of genius, try to prove

rigorously that there are no other possibilities of deforming matter that cannot be constructed by applying one or more

of the six above. Mathematicians have far more to say about things like that, all of which is incomprehensible to normal

people including me. |

| |

|

You realize, of course, that in a crystal lattice the upper row shows two edge

dislocations and a screw dislocation.

The lower row is also interesting. Applied to lattices it shows a possible elementary

defect called "disclination" that is, however, almost never observed in three-dimensional

crystals - but in two dimensional periodic structures. |

| |

| |

|

References:

V. Volterra, “Sulle distorsioni dei corpi elastici

simmetrici,” Rend. Accad. Lincei, vol. 14, 1905. V. Volterra, L'equilibre des corps élastique multiplement

connexes, Gauthier-Villars, Imprimeur-libraire, Paris, France, 1907. |

| | |

|

| |

|

| 1) |

I'm just back from an operetta gala performed in the Kiel opera with

stars from, e.g., the New York City Metropolitan - did I mention already that Germany has far more full-grown operas (84)

than any other country? My wife and I were fabulously entertained. Music from two Hungarian

composers was played, inspiring me to give you the following short list of Hungarian scientists and artists who made the

world a different place in the early 20th century.

Of course, many of these names go back to Austro-Hungarian times,

and that's why many of these persons wrote their things in German.

I only included names that even "normal"

people might recognize. This implies that "our" Hungarians from above, plus more than hundred others, are not listed! |

| |

- Theodore Herzl (Herzl Tivadar, 1860 - 1904), spiritual founder of Israel .

- Joseph Pulitzer, 1847 - 1911, newspaper publisher.

- László Bíró, 1899 -1985, inventor of the ballpoint pen.

- Andrew Grove (András Gróf, 1936 -), pioneer of the semiconductor industry, CEO of Intel.

- Rudolf (Rudy) Emil Kálmán, (1930 -), inventor of the Kalman filter know to all (electrical) engineers

- Eugene Wigner (Wigner Jeno, 1902 -1995), physicist; Nobel prize 1963

- Dennis Gabor (Gábor Dénes,1900 - 19 71), inventor of holography, physics Nobel prize 1971.

- John Charles Polanyi (Polányi János 1929 -), chemist; son of "our" Polanyi here; Noble prize 1986.

- Elie Wiesel (1928 - 1986). Peace Noble prize 1986

- John von Neumann (1903 – 1957). Extremely famous mathematician.

- Theodore von Kármán (Szolloskislaki Kármán Tódor, 1881 – 1963), very famous physicist.

- Leó Szilárd (Szilárd Leó, 1898 – 1964). Physicist and inventor who conceived

the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear reactor with Enrico Fermi, and in late 1939 wrote the

letter for Albert Einstein's signature that resulted in the Manhattan Project that built the atomic bomb. He also conceived the electron microscope.

- Edward Teller (Teller Ede,1908 – 2003). Physicist, known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen

bomb".

- Paul Abraham (Pál Ábrahám 1892 - 1960). Composer of operettas, e.g. "Viktoria und ihr

Husar", "Die Blume von Hawaii".

- Emmerich (or Imre) Kálmán (1882 – 1953). Composer of operettas, e.g. "Die Csárdásfürstin",

"Gräfin Mariza", or "Die Zirkusprinzessin".

- Sir Georg Solti, (1912 – 1997). Conductor .

Incidentially, the list of famous jewish Hungarians is pretty much identical to

the list of famous Hungarians. |

| |

| |

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)