| |

Invention or Discovery? |

|

Did the fathers (and mothers) of quantum theory, (statistical) thermodynamics,

theory of relativity and so on invent the basic laws of those science fields or did

they find them? This is a meta science question; a

question not of science but about science. An answer

thus must come from philosophy, not from science.

Philosophy can't tell, however. This

might appear surprising but ask yourself: when was the last time that philosophy actually could tell something by making

an unambiguous statement about some basic truth? |

|

|

Actually, it's pretty much only philosophers

that can't tell. Everybody else can. So, what exactly is the question? |

|

Invention implies that the laws of nature

as we know them are figments of human "thinking", whatever that implies, and given to changes as the way of thinking

changes as time goes on. Non-humans like your cat, husband or goldfish, not to mention those slimy aliens out there, would

have their own points of view about those laws, quite different from ours. There is no such thing as an absolute truth.

Could that be the (absolute?) truth? |

|

|

Aristotle's "laws of nature"

were quite different from what we have now (and completely wrong). The "phlogiston"

of old, just as the "ether" of not so old, gave way to thermodynamics and electrodynamics as we know it now. It follows that what we think or believe now will be

quite different from what we will think or believe in the future. All of that is just made by humans and has no absolute

significance whatsoever.

It also follows that other beings capable of "thinking" on some other planet or at

some other time will invent something else for explaining nature that suits their particular

needs. There is no such thing as absolute truth; at best we can come up with some crude approximations to something that

is elusive, if existent at all, like you, for example. |

|

Finding implies that the basic laws of nature

exist independent of humans or aliens out there, and that we can find some of the basic laws or perhaps, in due time, all

of them if their is number is finite. Platon (and a throng of

others) comes up in this context but I will not belabor that. |

|

|

Absolute truth then exists in the form of definite natural "laws". We can find them

or at least parts of them. When we describe these laws in the languages available to us (including the language of mathematics)

we are forced to use approximations because our tools are not fully up to the task.

Look at your wife (or just somebody)

and assume that her existence is a kind of absolute truth. Now describe her completely.

You quite simply can't (the attempt probably would be dangerous, anyway). But does that imply that your wife does not exist

exactly as she is? The "true name" concept comes

in here as a mythical solution to the problem. |

|

So what shall it be? Are we going to abandon the concept of atoms one day and

replace it with something else? |

|

|

All scientists and most "normal" folks definitely say no!

Some—not all—scientific discoveries are absolute and will never change. Maybe the way we describe

atoms will change but they are the same atoms. |

|

|

Most professional philosophers tend to say yes! They would

invoke a lot of big words like positivism, positive relativism, postmodernism, deconstructivism, and so on and simply deny

that atoms have a reality on their own that is independent of what philosophers think. Everything is a human invention.

Strange, though, that they never invented anything useful. |

|

Well, those philosophers are wrong. It is as simple as that. They stick to the

time-honored tradition that philosophers were nearly always wrong when they "think" about science. Aristotle,

for example, was always wrong about scientific topics, even on subjects where he could have known better. That does not mean that

he didn't do great things in other areas! |

|

|

As an example, for Aristotle steel was especially

pure iron: “Wrought iron indeed will melt and grow soft, and then solidify

again. And this is the way in which ‘steel’ is made. For the dross sinks to the bottom and is removed from below,

and by repeated subjection to this treatment the metal is purified and ‘steel’ is produced"

Well. He

is utterly wrong and will remain to be wrong till the end of days or hell freezes over, whatever comes first. |

|

|

What can you do with philosophers like this? Here is a thought: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

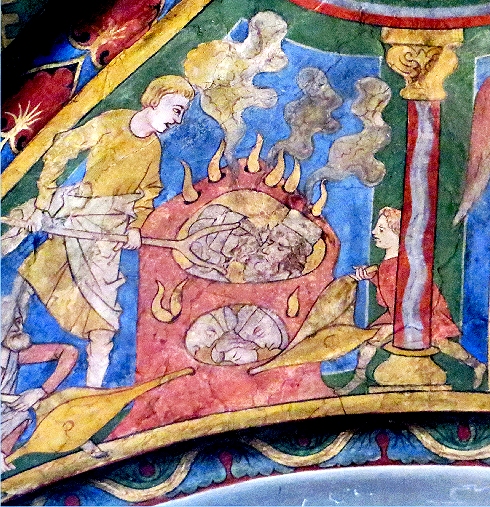

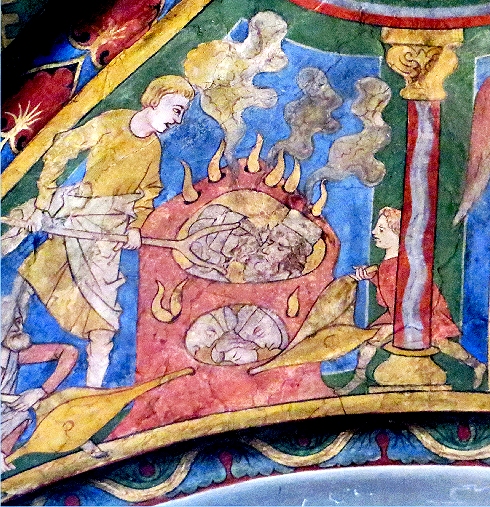

| Source: Photographed at the St. Maria Lyskirchen in Cologne (Köln), Germany, 2016 |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Smelt them! I get somewhat ahead of myself here but smelting is the process where you turn not-so-useful

ingredients into something desirable, like iron oxide into iron. How it is done can be seen in this painting from the middle

of the 13th century that adores a ceiling of the St. Maria Lyskirchen in Cologne (Köln) Germany. |

|

|

OK, you nit-pickers out there! Yes, the picture actually shows the "burning"

of the philosophers after they had been converted to Christianity by St Catherine (the one with the wheel). Considering

that Christian philosophy is even worse than the heathen stuff

of Aristotle and his ilk, the emperor (one Maxentius or Maximin) had no more use for the guys and wanted them burned. This

was traditionally done at the stake but the artist of the picture above probably thought that this was wasteful and that

one could at least try to do better. His philosphers are cleary fed to a smelter, a typical "Rennofen" of the

time. Burning something just produces CO2 and ashes, while smelting might turn those guys into something useful

like court jesters, maybe.

Well - it didn't work but there is no harm in trying. |

| | |

|

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)