|

Lattice and Crystal - Simple View |

| |

What is a Lattice? |

|

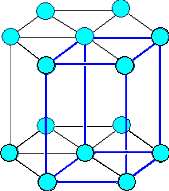

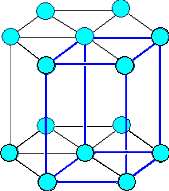

A lattice is a mathematical thing. It is simply

a periodic arrangement of mathematical points in space, extending to infinity in all directions. Here is a picture of a

part of a lattice (It's hard to draw infinitely large pictures): |

| | |

|

|

|

| |

A correct picture of a mathematical lattice consisting of a

periodic arrangement of mathematical points in space. |

|

| | |

|

|

|

If you don't see much you have to look harder. Mathematical points, after all,

are infinitely small. |

|

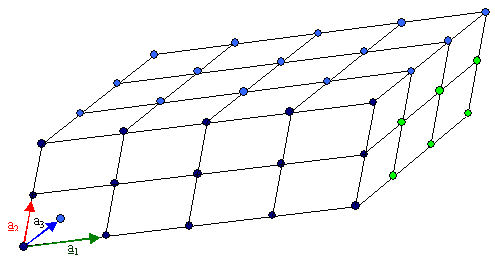

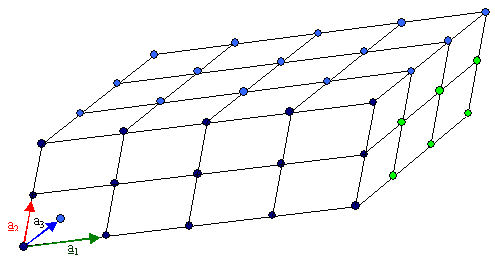

OK - you can't find your good glasses, I understand. So let me help

you by showing that picture of a periodic arrangement of points in space once more but with some of the points now symbolized by little spheres: |

| |

| |

| |

|

| A mathematical lattice of points, symbolized by little

spheres in space. |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Not all that great either? So let me help you once more by introducing some lines and colors

to guide the eye: |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

A mathematical lattice of points, symbolized by little

spheres in space,

plus some lines to guide the eye, and with points inside and outside the "block"

omitted. |

|

| | |

|

|

Now we "see" it - except we see all kinds of things that are not really

"there" and we do not see things that actually are there, like the "inside" points or the points out

there up to to infinity.

There is just no way to produce a "correct"

picture of a lattice or of a crystal that is of any use to mere humans. More about the problems with drawings of lattices

/ crystal in this link. Of course, if you are not a mere human but a mathematician,

you don't need pictures. You actually hate them (to the extent you are capable of having emotions) because they are so imperfect.

A few simple and beautiful equations are so much better. |

|

|

What even we imperfect humans gather from the the figure above is that all the essential information

about the lattice shown is contained in the three arrows or vectors in the left-hand corner. Three arbitrary

arrows with respect to lengths and mutual orientation can describe any lattice whatsoever - just repeat them. However, if

we want to go beyond this general case and try to differentiate with respect to some special

lattices, we find that there are 13 special cases. Together with the general and least symmetric case, we have a grand total

of 14 Bravais lattices, as they are called. The link gives the in-depth view of

lattices and crystals. |

|

|

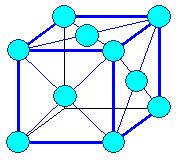

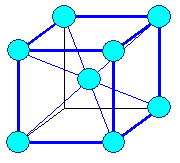

Some special cases emerge if we define some conditions for the three vectors defining a lattice.

We might, for example, demand that they all must have exactly the same length a and should be at right angles

to each other. This is actually the definition of the sides of a cube and the "cubic

primitive" Bravais lattice results.

From a purists point of view, you do not have to do this. It's like classifying

humans, for example, into "friends, Romans, countrymen". It doesn't' change a thing with respect to the real humans

being around, but it makes life easier.

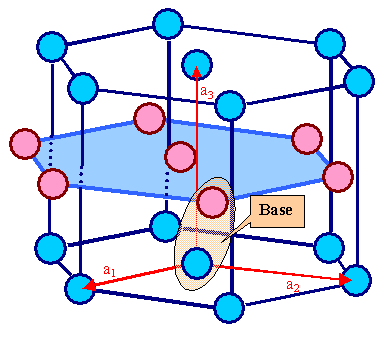

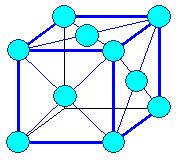

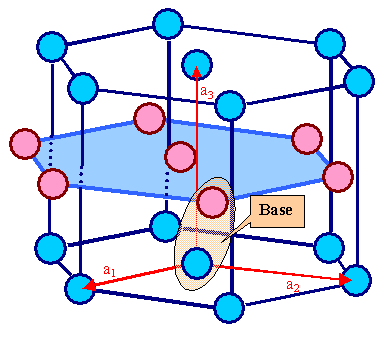

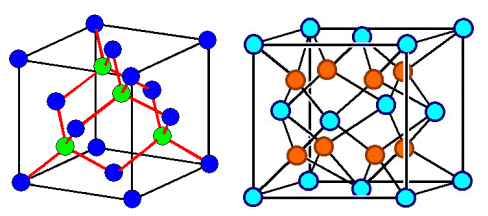

Here are the three most important Bravais lattices: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cubic face centered | Cubic body centered |

hexagonal |

| The three most important Bravais lattices. |

|

| | |

|

| |

What is a Crystal? |

|

A crystal results when you put exactly the same arrangement

of atoms, called a "base", at every lattice point of some Bravais lattice.

In the most simple case you put just one atom on a lattice point. |

|

|

If we do that with the three lattices above, I don't have to redraw the figure.

We can now take the blue spheres to symbolize atoms, and - Bingo! - we have a schematic

drawing of some crystals. Of course, in a correct drawing the circles symbolizing atoms

should touch each other. But if we draw it this way, the figures will become utterly confusing as illustrated in this link.

Note that putting atoms on any lattice point of the hexagonal Bravais lattice does

not produce an hexagonally close-packed crystal. We need two

(identical) atoms in the base as illustrated below: |

|

| |

| |

|

| Hexagonal lattice and hexagonally close-packed crystal. |

|

| | |

|

|

|

The blue circles symbolize the lattice points of the hexagonal Bravais lattice and

some atom. The pink circles symbolize only the atom and for hexagonally close-packed elements it is same kind as the blue ones; Cobalt (Co), or Zinc (Zn),

for example. There are two atoms in the base. |

|

In the case of the face-centered cubic Bravais lattice, putting one

atom on each lattice point does produce a close-packed crystal. |

|

|

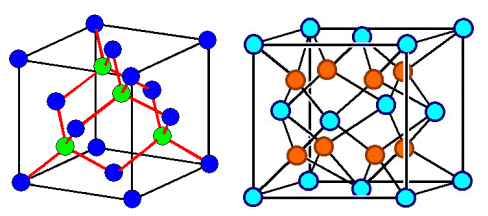

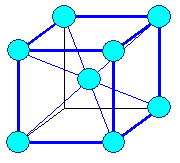

However, nobody can keep me from putting two or three atoms in the base, for example like this: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| Crystals with an fcc lattice and two or three atoms, resp., in the base. The blue circles

symbolize latice points and atoms, the other one only

atoms. |

| On the left we have the diamond-type crystals, on the right the zirconium-oxide type crystals. |

|

| | |

|

|

|

You figure out the the base. What we get this way are many kinds of different crystals for

the same lattice, depending on what groups of atoms or bases we put on a lattice point.

Note that the two crystals above,

while made from a close-packed lattice, are not

close-packed crystals!

Note also that I could have claimed, for example, that the

blue atoms are iron, and the green or red atoms are carbon. On paper a lot is possible. Mother nature, however, does not

give a damn about my or your claims; she just will not comply. Not everything you can draw on a piece of paper will be possible.

Only combinations of atoms that "want" to crystallize in some specific way will be found as real

crystals. While it is easy to analyze an existing crystal, it is not so easy to predict how a bunch of atoms will crystallize. |

|

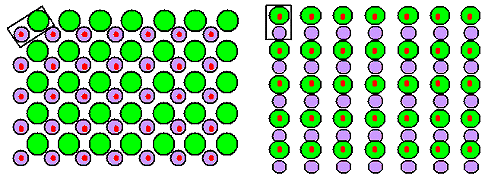

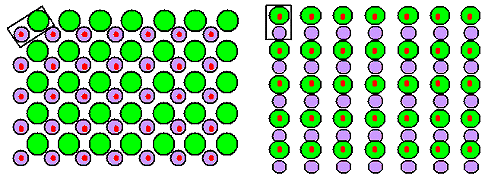

In the examples given so far, we had the base of atoms put on a lattice point

in some special way. There are, in principle, other ways too. If we pick some alternative, we get yet another crystal for

the same lattice. Here is a simple example: |

| |

| |

| |

|

| Two quite different crystals with a cubic primitive lattice (red

dots) and the same base (black rectangle) but arranged differently on the lattice points. |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Same lattice, same base - but different crystals.

Note once more: The fact that you can

draw this, does not mean that you can make it. Typically, only one of the many possibilities will be realized with real

atoms at a given temperature. |

|

Now you have at least a vague idea, why there are 230 different combinations (or

"point groups") of bases and Bravais lattices as

claimed in the main text. |

|

|

In the Hyperscript are several modules related to this topic and many examples for lattices

and crystals. Go and find them yourself! |

| |

| |

With frame

With frame

4.2.2 Being Iron

4.2.2 Being Iron

History of Carbon

History of Carbon

Group 1 / IA; Alkali Group

Group 1 / IA; Alkali Group

Group 2 / IIA; Alkaline Earth Metals Group

Group 2 / IIA; Alkaline Earth Metals Group

Group 12 / IIB; Scandium Group

Group 12 / IIB; Scandium Group

Group 12 / IIB; Titanium Group

Group 12 / IIB; Titanium Group

Group 5 / VB; Vandium Group

Group 5 / VB; Vandium Group

Group VIB; Chromium Group

Group VIB; Chromium Group

Group 7 / VIIB; Manganese Group

Group 7 / VIIB; Manganese Group

Group 8 - 10 / VIIIB; Iron - Platinum Group

Group 8 - 10 / VIIIB; Iron - Platinum Group

Group 11 / IB; Copper Group

Group 11 / IB; Copper Group

Group 12 / IIB; Zinc Group

Group 12 / IIB; Zinc Group

Group 13 / IIIA;

Group 13 / IIIA;

Group 14 / IVA; Carbon Group

Group 14 / IVA; Carbon Group

Group 15 / VA; Nitrogen Group

Group 15 / VA; Nitrogen Group

Group 16 / VIA; Chalkogenides or Oxygen Group

Group 16 / VIA; Chalkogenides or Oxygen Group

Group 18 / VII; Noble Gases

Group 18 / VII; Noble Gases

Group 1/ I; Hydrogen

Group 1/ I; Hydrogen

Group 3 / IIIB; Lanthanides or "Rare Earths"

Group 3 / IIIB; Lanthanides or "Rare Earths"

Group 17 / VIIA; Halogens

Group 17 / VIIA; Halogens

Bravais Lattices and Crystals

Bravais Lattices and Crystals

Alloying Elements in Detail

Alloying Elements in Detail

Crystal Models

Crystal Models

Transmission Electron Microscopes

Transmission Electron Microscopes

Producing "Nirvana" Silicon or Nearly Perfect Silicon Single Crystals

Producing "Nirvana" Silicon or Nearly Perfect Silicon Single Crystals

Needle Scanning Microscopes

Needle Scanning Microscopes

Light Microscopes

Light Microscopes

Microscopes for Science

Microscopes for Science

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)