|

Little needs to be said about the Lenses, Mirrors, and Prisms.

The basics have been covered before, here we just look at a few specifics to illustrate

a few additional points |

|

|

Below are two pictures that demonstrate what one can do with lenses and mirrors.

They are, after all, still the most important components of most optical systems |

| |

|

Here is a "lens" for a modern production "stepper"

i.e. the machine that projects the desired structure onto a light sensitive layer (the resist) on a Si wafer. Steppers are

crucial for making Si microchips. Here is the link

for details.

The producer of this lens is Carl Zeiss SMT AG , Germany. |

Although designed for manufacturing on a nanoscopic scale, a lithography stepper

lens is not small. The Starlith 1900i weighs more than a metric ton, stands several feet tall and is as big around as a

tree trunk. A catadioptric lens consisting of reflecting mirrors and refractive optics enables volume semiconductor production

at 40 nm resolution.

The stepper lens has a numerical

aperture of NA = 1.35 (huge!) and is intended for use in immersion lithography,

a technique that replaces the air gap between wafer and stepper with water or another fluid. Zeiss notes that the device

is, in some sense, the end of the art.

The lens is designed for an UV light

source with a wave length of 193 nm, which needs an ArF (yes, "Argon Fluoride") Laser. Remember that the visible spectrum ends around 400 nm. UV radiation from

the sun, for comparison, spans the range (315 - 400) nm ("Ultraviolet A") and (280

- 315) nm ("Ultraviolet B"). |

|

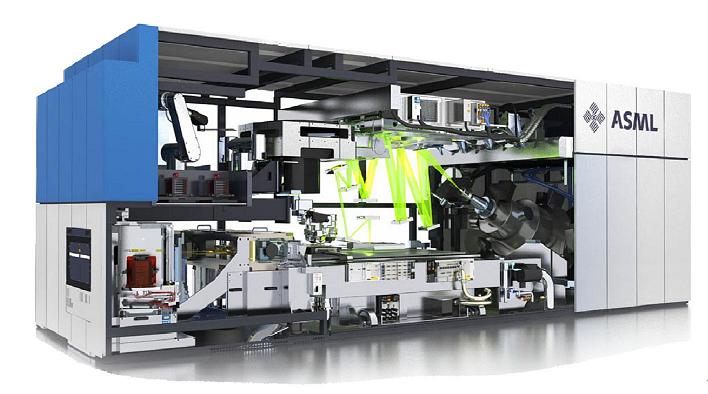

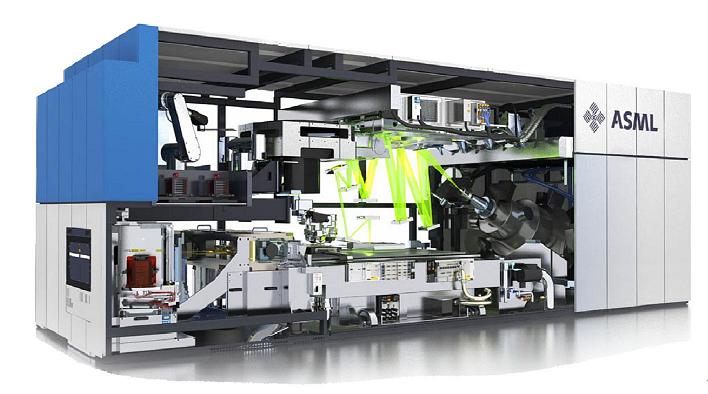

That is the kind of "projector" that will move into chip production after lenses

have reached the end of the art. It needs to operate in vacuum because air starts to

absorb light below around 185 nm.

The " NXE:3100" lithography machine from ASM corporation, employs extreme-ultra-violet (EUV) light with a

wave length of 13,5 nm to provide an imaging capability close to 20 nm. EUV will enabke 27 nm resolution down to

to below 10 nm eventually. How one makes an intensive 12.5 nm deep-UV light source is a rather interesting topic in its

own right.

The "optics" is based entirel on mirrors - with essentially atomically flat surfaces .

The

machine shown is a kind of pre-production prototype that is presently (2011) tested.

It is essentially still a slide

projector but a bit more expensive (around (10 - 20) Mio € would be my guess). |

Note added July 2021:

As it turns out, I was a bit conservative

in my coist estimation. You can buy the "most complicated machine" (New York Times) now for about 150.Mio $ |

|

| |

|

|

From a Materials Science and Engineering point of view, making those machines

is a big challenge but nothing more shall be said about them here. |

|

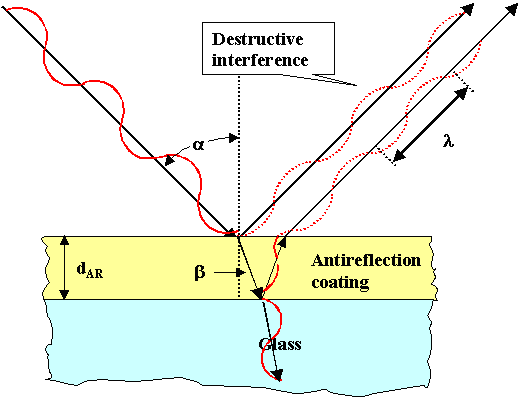

It goes without saying, however, that for any non-trivial system employing lenses

you need anti-reflection coatings; check your Fresnel equations! |

|

|

You also need anti-reflection coatings for solar cells (reflected light cannot produce electricity)

and in numerous or better almost all "optical" devices. .

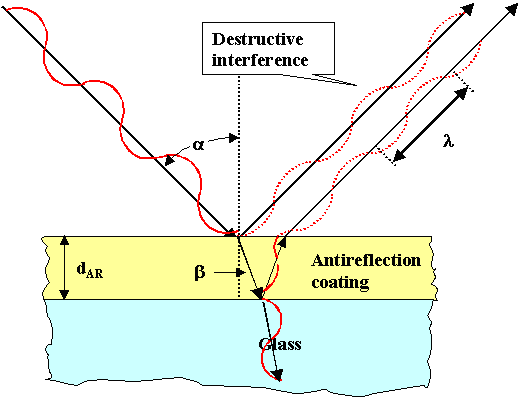

Here is the (known) working principle of a simple

antireflection coating (for one wavelength and angle of incidence). Since the two beams reflected from the surface and the

interface cancel each other exactly because of the 180o phase

difference, the incoming beam must go into the material in its entirety. If you noticed the little paradox contained in

this statement, activate this link. |

| |

|

Schematic view (don't look too closely at phases) of the working

of an antireflection coating. |

|

|

|

Of course, if you want to minimize reflection for a whole range

of wavelengths and angles of incidence, you have a problem. The answer to the problem, as ever so often in Materials Science

is: compromise! Achieving perfect antireflection for those conditions is next to impossible or at least expensive. |

| |

|

|

Now that we have lenses and mirrors covered, we need polarizers, diffraction gratings,

and filters next. |

| |

|

|

We have already covered a lot of ground with respect to

polarization and encountered some ways to produce a polarized beam. There

are two basic ways to achieve linear polarization: |

| |

|

|

|

Absorbing linear polarizers are essentially of the "array of conducting rods" type

as outlined before. Not much more needs to be said here.

|

|

Foil polarizers of this type are used most of the time- whenever utmost quality is

not the concern. They are essentially based on Lang's old invention. |

|

|

Instead of (birefringent) herapathite crystals embedded in a stretched plastic foil, we now

use aligned (again by stretching) polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) foils and dope the molecules with Iodine. In other words, we produce a more or less conducting polymer in one direction. Polarizing

foils of this type are most common type of polarizers in use, for example for sunglasses, photographic filters, and liquid

crystal displays. They are also much cheaper than other types of polarizer. |

|

|

A modern type of absorptive polarizer is made of elongated silver nanoparticles embedded in

thin (» 0.5 mm) glass plates. These polarizers are more durable, and can polarize

light much better than plastic Polaroid film, achieving polarization ratios as high as 100,000:1 and absorption of correctly-polarized

light as low as 1.5%. Such glass polarizers perform best for short-wavelength infrared light, and are widely used in optical fiber communications.

|

|

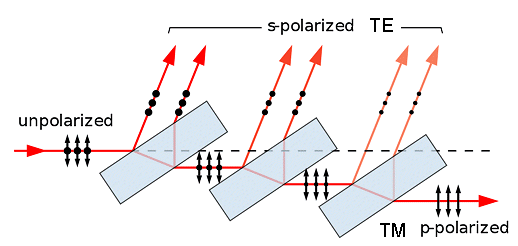

Beam-splitting polarizers come

in many varieties and two basic types: |

|

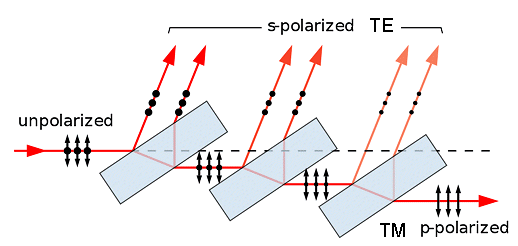

1. Use simple materials and employ the Brewster angle. |

|

|

The reflected light then will be linearly polarized (TE case) because

the TM components of the incident light are not reflected at all (figure it out yourself!) |

| |

|

| The quality improves with the number of reflections but the intensity goes down. |

|

|

|

Doable but not very elegant. Think about using this method for sunglasses or

3-D glasses. On the other hand, if you need to polarize in the deep UV or IR, it might be your only

choice. |

|

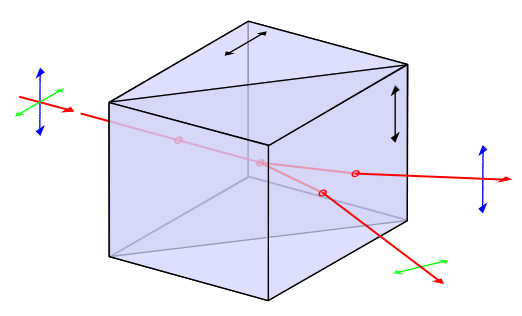

2. Use tensor materials

or in other words effects like birefringence. |

|

|

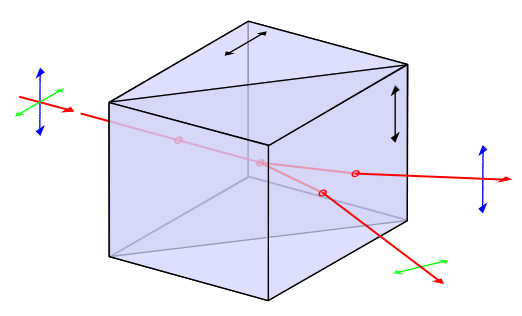

Use birefringence, e.g. in the form of a Nicole

prism, Wollaston

prism, or a number of other "Prisms". |

| |

Nicol prism |

Wollaston prism |

|

|

|

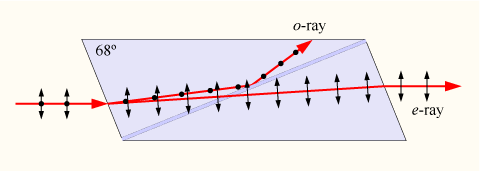

All those "prisms" use birefringent (or tensor) materials, typically the easy to

get or make calcite

CaCO3. The incoming beam splits into an ordinary and extraordinary beam that can be fully polarized. In

the Nicol prism the geometry is chosen in such a way that the extraordinary beam undergoes total reflection at the interface

where the two parts of the crystal are joined. The ordinary beam is not only full polarized but continues in the same direction

as the incoming beam. The Nicole prism is therefore relatively easy top use in optical equipment. |

|

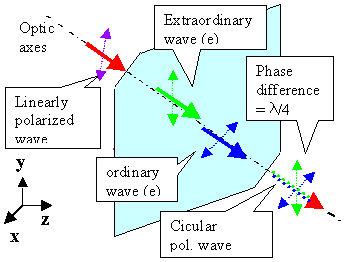

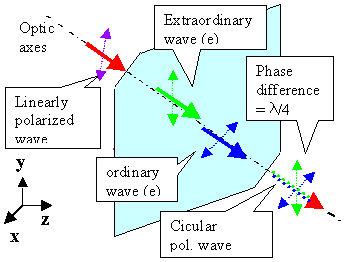

Achieving circular

polarization is also "easy" in principle. All you need is a linear polarizer and a "quarter wave plate". |

|

|

A "quarter wave plate" is a (typically thin) piece of material, where a polarized

beam goes in, and two beams come out with the following properties:

- They two beams are linearly polarized with polarization directions perpendicular to each other

- The two beams have equal intensities

- One beam is phase shifted by exactly a quarter wave length (l/4) with respect to the

other.

|

|

|

The two waves thus produced superimpose to a circular polarized wave as shown below: |

| |

|

|

The incoming beam is polarized at 45o relative to the principal polarization directions

in the anisotropic medium.

The two beams exciting the medium produce a circular polarization as shown in the animation

(© Wikipedia) |

|

|

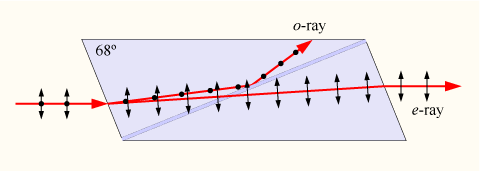

How is it done? Let's look at the "old"

and slightly modified picture above to understand how it is done in principal. |

|

|

We need an anisotropic material oriented with respect to the optical axis in such a way that

the ordinary and extraordinary beam are parallel. The two beam than will automatically have defined linear polarizations

at right angle to each other.; condition 1 is met. |

|

|

We polarize the incoming beam linearly in such a way that its polarization direction is at

45o to the polarization direction in the anisotropic crystal. It then will split in two beams that have

equal intensities. Condition 2 is met. |

|

|

The ordinary and extraordinary beam travel with different velocities inside the material.

The ordinary beam - that's why is is called "ordinary" - travels with cO = co/no

but the extraordinary beam does not; it travels with a speed cEO = co/ne.

Whatever the "extraordinary" index of refraction ne will be, after traveling some distance

d the phase shift between the two waves will be l/4 Obviously we have

|

| |

|

|

|

So all we have to do is to cut our anisotropic material to the thickness d and

condition 3 is met. |

|

Looks complicated? Well, that's because it is complicated. In principle and whenever

you make your "lambda quarter plate" from a single crystal (like mica;

the most prominent crystal for doing this) |

|

|

So next time you watch a 3-D

movie, gives those (obviously cheap) glasses you're being handed a closer look. They contain two circular polarizers:

one eye with a left-handed polarization, the other one with a right-handed one. And obviously they are really cheap. So

how is it done? |

| |

| |

|

We want to shift the phase of some light beam for various reasons; here we look

at just two: |

| |

- We wan to do sub-micron lithography for making microelectronic chips with structure sizes dmin

considerably smaller than the wave length l

- We wan to make a hologram

|

|

Let's look at phase shift masks for the

ultimate in lithography first. |

|

|

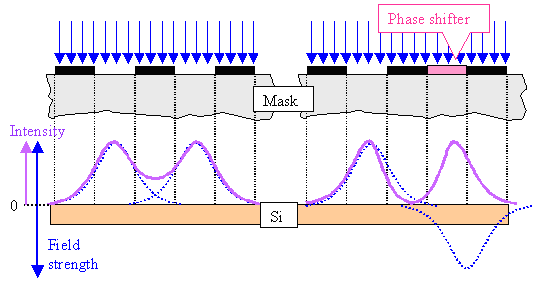

Right above we have data for the ultimate lens for lithography:

Numerical aperture NA = 1,35, l = 193 nm, so

dmin = l/ 2NA = 71,5 nm; larger than what we want to get. So how are

we going to beat the limits to resolution dictated by diffraction optics? By using a phase shifting mask (PSM). The principle is

shown in the figure below: |

|

|

|

|

|

Remembering that waves "bend" around corners,

it becomes clear that if two corners are very close together as in the schematic outline of a mask (or reticle) used for making the smallest possible structures

on a chip, the "around the corner" waves overlap and from an electrical field strength and intensity (field strength

squared) profile as schematically shown. The two structures are no longer fully resolved; there is an appreciable intensity

below the middle light blocking layer on the mask. |

|

|

Now we introduce a "phase shifter", something the shited the phase of the light

going through the right part of the struntre by 180o. This changes the sign of the electricl field strength

as shown. |

|

There is far more but let's forget it for this leture course. Go to the next one. |

| |

|

© H. Föll (Advanced Materials B, part 1 - script)