|

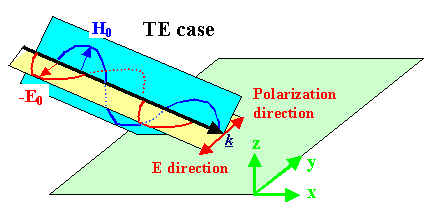

Let's look at the TE mode

(or _|_ mode) once more but now with the coordinate system needed for the equations

coming up. |

| |

|

|

|

The electrical field of the incoming beam thus writes as Ein

= (0, Ein, 0), i.e. there is only an oscillating component in y-direction. For

the y-component Ein we can write Ein = Ein,

0exp[–i(kinzcosa + kinxsina)], decomposing the wave in an z and x component. We omitted

the wt phase factor because it will drop out anyway as soon as we go to intensities.

|

|

|

Next we should write the corresponding equations for the reflected wave and the transmitted

wave (requiring changes in the k-vector). |

|

|

Then we need the same set of equations for the magnetic field. For that we have to know how

the magnetic field of an electromagnetic wave can be derived from its electrical field. That means back to the Maxwell equations

once more or for a taste of that to sub-chapter 5.1.4. |

|

|

After you did that you consider the boundary

conditions as outlined before.

Now you can start to derive the Fresnel equations. You, not me. It's tedious but good

exercise. Let's just look at the general way to proceed. |

|

First we write down the continuity of the tangential or here parallel component

of E (and always same thing for H in principle). Since E

has only components in y-directions we have for those components |

| |

|

|

|

While this looks a bit like the energy or intensity conservation

equation from before, it is not! It is completely

different, in fact! Our E's here are field strengths and not energy! |

|

So let's look at the energy flux in z-direction now, as given by

the Poynting vector S. It must be continuous

since energy is neither genererated nor taken out at the interface as noted before.

With the relation for energy from before and dropping the index "0"

for easier writing and reading, we obtain |

|

|

| e1½ [(Ein)2 –

(Eref )2] · cosa |

= |

e2½ (Etr)2 ·

cosb |

|

|

|

|

This equation is simply the good old Snellius law in slight

disguise (figure it out yourself, noting that Itr = Iin – Iref).

|

|

Dividing that equation by the one above it (remember: (Ein)2

– (Eref )2 = (Ein – Eref ) · (Ein

+ Eref ) gives |

|

|

| e1½ [Ein – Eref

] · cosa | = |

e2½Etr · cosb

|

|

|

|

|

With the good old relation (e1/e2)½ = n1/n2 = sina/sinb (with a and b as given

in the old figure for simplicity) and some shuffling of terms we finally obtain

the Fresnel equations for the TE case . |

| |

Fresnel Equations TE case

| Eref | = |

Ein · |

sinbcosa – sinacosb

sinbcosa + sinacosb | = |

– Ein · |

sin(a – b)

sin(a + b) | | |

| | |

| | |

| Etr | = |

Ein · |

2sinbcosa

sin(a + b) |

| |

| |

|

|

|

Going through the whole thing for the TM case (something I will not do

here) gives the Fresnel equations for the TM case |

| |

Fresnel equations TM case

| Eref | = |

Ein · |

sinbcosb – sinacosa

sinbcosb + sinacosa | = |

– Ein · |

tan(a – b)

tan(a + b) | | |

| | |

| | |

| Etr | = |

Ein · |

2sinbcosa

sin(a + b) · cos(a

– b) | |

| |

|

|

|

A first extremely easy thing to do is to calculate the Fresnel

coefficients for normal incidence (a = 0o). What we get for the standard case

of going from air (less dense medium, n = 1 to some appreciable n (denser medium) for both the TE and TM case is |

| |

Eref

Ein |

| = – |

n – 1

n + 1 |

| | | |

| | |

Iref

Iin | |

| = |

æ

ç

è |

n – 1

n + 1 |

ö

÷

ø |

2 |

|

|

|

|

In other words, shining light straight on some glass with n = 2 means that almost

10 % of the intensity will be reflected! This has immediate and dire consequences for optical instruments: you must provide some "anti-reflection"

coating - otherwise your intensity gets too low after the light passed through a few lenses.. |

|

We need to do a bit of exercise here: |

| |

|

|

|

If we now speculate a little and consider metals as a material with very

large dielectric constants and thus n, it is clear that they will reflect almost 100 %. |

|

Next we plot the Fresnel coefficients as a function of a,

the angle of incidence. We need four figures with 8 graphs to get the major points clear: |

| | |

- Two figures showing the relative field strength (Eref/Ein), always with two

separate graphs for the two basic cases TE and TM.

1. Case 1:

n1 > n2, i.e. going from the less dense to the optically denser material

2. Case 2:

n1 < n2, i.e. going from the optically denser to the less dense material

- Two figures showing the relative intensity (Eref/Ein)2,

always with separate graphs for the two basic cases TE and TM; same cases as above

|

|

First we look at case 1 with n1

< n2, i.e. going from the less dense to the optically denser material |

|

|

We take n1/n2 = ½ e.g. going

from air with n = 1 into some glass with n = 2. |

|

|

Here are the 4 graphs for this case; we look at the reflected beam. |

|

Case 1: Going from an optically less dense (n = 1) into a dense

(n = 2) material

Electrical Field

E/E0 |

Reflected beam |

Intensity

(E/E0)2 |

|

|

|

Let's look at the field strength first What we see is |

| |

- The numbers are negative for small a or almost perpendicular incidence. This means

that we have a phase shift of 180o between the incident and the reflected wave as outlined

before.

- The relative amplitude of the transmitted beam is simply 1 - Eref/Ein. It

becomes small for large a's.

- In the TM case the field strength is exactly zero at a certain angle aB

or "Brewster

angle". This means that there is no reflection

for this polarization; all the light will be transmitted.

- So if the incident light consists of waves with arbitrary polarization, the component in TM

direction will not be reflected and that means that whatever will be reflected must be polarized in TE direction. We have a way to polarize light!.

- For grazing incidence or large a's almost all

of the light will be reflected in either case.

|

|

Looking a the intensities does not show anything new; you just see the "strength"

of the reflected beam more clearly. |

| |

|

|

Now let's look at case 2 with n1 > n2,

i.e. going from the more dense to the optically less dense material |

|

|

We take n1/n2 = 2 e.g. going from

some glass with n = 2 into air with n = 1. |

|

|

Here are the 4 graphs for this case. |

|

Case 2: Going from an optically dense (n = 2) into a less dense

(n = 1) material

Electrical Field

E/E0 |

Reflected Beam

|

Intensity

(E/E0)2 |

|

|

|

Let's look at the field strength first What we see is |

| |

- The numbers are positive for small a or almost perpendicular incidence. This means

that we have no phase shift of 180o between the incident and the reflected wave as outlined

before. Not that the reflected wave is the one staying inside the optically dense material.

- The relative amplitude of the wave leaving the material is simply 1 - E/E0. It goes

to zero rather quickly for increasing a's

- In the TM case the field strength is exactly zero at a certain angle aB

or "Brewster

angle". This means that there is no reflection

for this polarization, all the light will be transmitted. Note that the value for the Brewster angle here is

different from the one in the case going from the less dense to the more dense material.

- So if the incident light consists of waves with arbitrary polarization, the component in TM direction will not

be reflected and that means that whatever will be reflected must be polarized in TE

direction. We have a way to polarize light inside a material!

- At some critical angle

acrit all light in either mode will be reflected. Beyond acrit

the Fresnel equations have only complex number solution and that means there is no field strength or energy outside the

material. Light waves impinging at an angle >acrit will be reflected right

back into the material. acrit is also known as the angel of total reflection.

- That means that only light within a cone with opening angle < acrit

will be able to get of the material. It should be clear to you that a serious problem concerning light emitting diodes, (LED) is encountered here.

|

|

It's time for another exercise: |

| |

|

| |

|

© H. Föll (Advanced Materials B, part 1 - script)