|

We have a (monochromatic, coherent, polarized) light beam (a plane wave in other

words) and a piece of material. We direct our idealized "perfect" beam on the material and ask ourselves: what

is going to happen? |

|

|

First we have to discuss the properties of the material a bit more. It might

be:

- Optically fully transparent for all visible wavelength (like diamond or glass ) or

optically opaque (like metals).

- Optically partially transparent only for parts of the visible wavelength (like GaP

or all semiconductors with bandgaps in the visible energy range) or colored glass.

- Opaque and black (= fully absorbing) like soot or highly reflective (like a mirror).

- Perfectly flat (like a polished Si wafer) or rough (like paper).

- Uniform / homogeneous (like glass or water) or non-uniform (like milk: fat droplets in water).

- Isotropic (like glass) or anisotropic (like all non-cubic crystals).

- Large (like anyything you can see) or small (like the Au nanoparticles in old church window that produce the red color).

|

|

|

I'm not sure I have exhausted the list. Be glad now that for the time being we look at a simple

and "perfect" light beam and not at real light.falling on a real

material. |

|

|

So we have a tall task before us. We first make it a bit easier by considering only flat,

uniform, isotropic and transparent materials like glass or (transparent) cubic single crystals like diamond. |

|

All that can happen for these

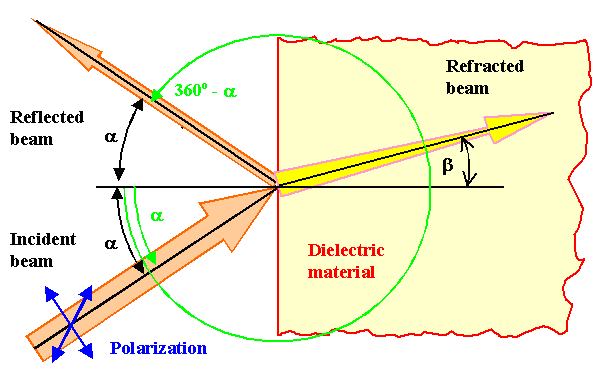

rather ideal conditions is shown in the following picture: |

| |

|

|

In essence we have an incoming beam, a reflected

beam and a diffracted beam that "goes" into

the material. |

|

|

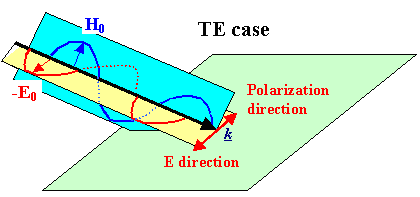

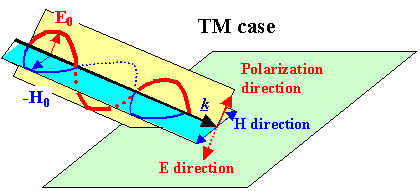

The incident "perfect" beam must have some kind of polarization. Even if it is unpolarized we should from now on think of

it as consisting of two linearly polarized parallel beams with equal intensity and polarization

directions differing by 90o. Same thing for the two other beams. Consider them to be two

beams with a 90o difference in polarization direction. This is important! |

|

|

We must expect that the reflected and diffracted or transmitted

beams might be polarized, too, but we must not assume that their polarization is the

same as that of the incoming beams. We deal with that in the next sub chapter. |

|

|

The situation in the picture above is very slightly simplified because we don't consider so-called

"evanescent waves" at the interface, and we only discuss a linear system

- the frequency of the light doesn't change. There are no beams with doubled frequency, for example (can happen in some crystals).

|

|

What do we know about the three (times two) light

beams shown?

I'll drop the plural from now on. But remember: think of all beams as consisting of two

linearly polarized parallel beams with equal intensity and polarization directions differing by 90o. |

|

Incoming beam. We know all about the incident beam because we "make"

it. In the simplest case it's a plane wave with an electrical field given by E = E0expi(kin

· r – wt) or, if you prefer, E

= E0cos(kin · r – wt).

The basic parameters of the incident beam are: |

|

|

- Intensity: We can describe the intensity Iin by

looking at E02, the square of the electrical field strength amplitude. In the particle

picture it would be the number of photons per second. In regular or technical optics, we have special units, "invented"

for dealing with light but we will not cover that here.

- Frequency: We assume monochromatic light with the circle frequency w.

- Polarization: We assume some arbitrary constant polarization (= direction

of the E vector). By definition, the polarization direction is perpendicular to the direction of the

wave vector k. We have only one beam now (the intensity of the

second one is zero).

- Phase: We can pick any initial phase since it's

numerical value depends on the (arbitrary) zero point of the coordinate system chosen.

Note that by just picking a

direction (like this — ), you have not yet decided where the tip of the vector is (—>

or <—), so we must pick that too. Switching to the other direction then implies a phase

change of 1800 or p

or reversing the sign of E.

- Coherence: We always assume full coherence, i.e. there is only one

phase. An incoherent beam, for comparison, would be a mixture of beams like "our"

beam but with different (= random) phases.

|

|

|

Since we assume a linear system, we can always discuss

"colored" light by discussing each frequency separately. We also can deal with arbitrary polarizations by decomposing

it into the two basic polarizations considered below which we need to discuss separately. An arbitrary polarization then

is just a superposition of the two basic cases; we are back to our "two beam" picture from above. |

|

Reflected beam:. The reflected beam will essentially

be identical to the incoming beam except for |

|

|

- Intensity: The intensity Iref will be different from that of the incoming beam; we have

0 < Ire < Iin.

- Direction: We know that we have a mirror situation i.e. aout

= ain. Note that its actually aout

= 360o –ain if you measure the angles in one

coordinate system. Why we know that we have a mirror situation is actually a tricky

question!

- Phase: We might have to consider that the phase of the reflected beam changes at the surface of the material.

|

|

Refracted beam: The refracted or transmitted beam runs through the material. We know that there is always some attenuation, damping, extinction

or what ever you like to call it. I will call it attenuation. What do we

have to consider? |

| |

- Intensity: We know from energy conservation that Itr(z

= 0) = Iin – Ire.

- Attenuation:

We expect exponential attenuation according to Itr(z) = Itr(z

= 0) · exp–z/aab if we put the z-direction

in the direction of the transmitted beam for simplicity. The quantity aab

obviously is an absorption length, giving directly the distance after which the intensity

decreased to 1/e or to about 1/3.

- Direction: Snellius law applies, i.e. sina/sinb

= n. We also know that the index of refraction n is given by er,

the "dielectric constant"; we have n = (er)½.

- Phase: We might have to consider that the phase of the transmitted beam changes at the interface of the material.

|

|

While we seem to know a lot already, some tough questions remain, essentially

relating to intensities, phases and attenuation as a function of the polarization, the angle of incidence, and the properties

of the material. |

|

|

As it will turn out, dealing with attenuation is easy.

All we have to do is to remember that we replaced the simple "dielectric constant" er

some time ago by a complex dielectric function

e(w) = e'(w)

+ e''(w). Since the index of refraction is simply given

by the square root of the dielectric constant, we might expect that the dielectric function not only contains the index

of refraction but additional information concerning attenuation. We will look at that in sub-chapter

5.2.3 in more detail. |

|

|

The questions relating to intensities and phases

will not go away that easily, however. We will see how to find answers in the next sub-chapter. |

| |

|

|

Going beyond that, however, needs some work. We must, in essence, start with the

Maxwell equations, look at the

"electromagnetic wave" case and solve them for the proper boundary conditions at the boundary of the two media. |

|

|

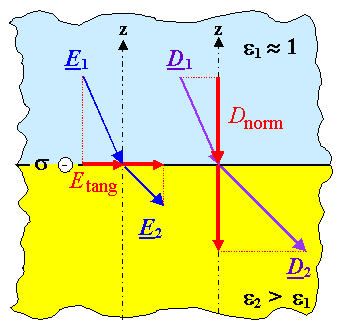

Or do we? Actually, we don't have to - as long as we remember (or accept) that

there are simple boundary conditions for all the fields coming up in electromagnetism

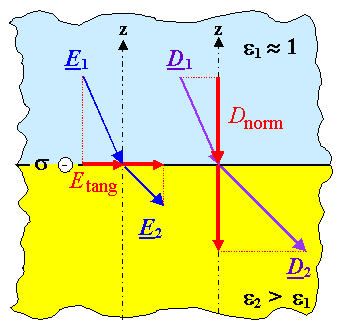

as illustrated below: |

|

|

|

| Electrical field

E | |

Etang = const |

| | |

|

Dielectric displacement

D = e0erE |

|

Dnorm = const. |

| | |

| Magnetic field H |

| Htang = const |

| | | |

Magnetic induction

B = m0mrE |

| Bnorm = const |

|

|

|

The picture shows some interface between two (dielectric) materials. In the picture

the first one is something like air or vacuum (er

» 1) but the relations holds for all possible combinations. How do we derive the boundary

conditions? |

|

|

It's easy. For an electrical field you need a gradient in some charges. For a change of an

electrical field vector you need an additional charge gradient right at the place where the field vector is supposed to

change. In the above case, for a change on the tangential component you would need a lateral gradient in the charge distribution

on the surface. |

|

|

If you understood chapter 3,

you know that some surface charge with an area charge density s is generated by polarization.

Looking long enough at Gauss' law will show that a lateral charge

gradient cannot exits. The tangential components Etang of E therefore

must not change going across the boundary. The normal component, in contrast, must change

because we do have an addition charge gradient perpendicular to the surface. |

|

|

Using related arguments makes clear that for the dielectric displacement D

the normal component must remain constant. For the magnetic field H and the magnetic flux density or

induction B corresponding relations apply. You might reason that this provides the definition of D

and B. It's just extremely useful to have vectors meeting those boundary conditions. |

|

Fortified with these boundary conditions, valid for any fields including the rapidly

oscillating electric and magnetic fields of light, the derivation of the Fresnel equations

- that's what we are after - is not too difficult as we will see in the next sub-chapter. |

| | |

|

© H. Föll (Advanced Materials B, part 1 - script)