|

Dieser Modul ist in Englisch, da

er auch in anderen Hyperskripten gebraucht wird.

Some variables are not

written in italics for ease of writing |

| |

|

Lets see what happens if we pull a crystal apart by applying sufficient force

(this is always possible, remember the first law of material science :-) |

|

|

The force needed to move an atom off the equilibrium position at r0

in the potential U(r) is given by dU/dr (the negative sign used in the definition of a potential is always the restoring force, i.e. the force that drives a particle

in the direction towards the potential minimum). |

|

|

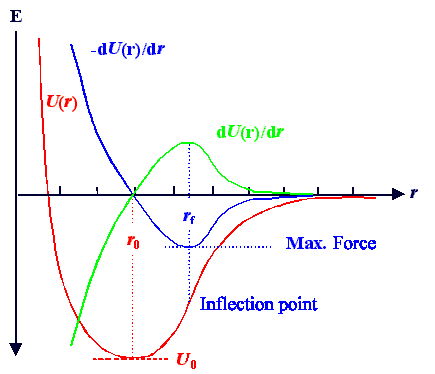

A schematic drawing of a typical potential well together with dU/dr is

shown below. |

| |

|

|

We notice several features: |

|

|

1. At the potential minimum at r0 , the force must be zero.

2. If the force curve is rather linear in going through r0, the potential around r0

is rather quadratic, we have a small thermal expansion and the vibration will be a harmonic

oscillation.

3. The force goes through a maximum at r = rf. This means that dF/dr

|rf = 0 and thus d2U/dr

2 |rf = 0. rf thus is the position of the inflection point

of the potential curve. |

|

What does the force maximum mean? Simple: |

|

|

Moving the atom to the point rf needs the ultimate amount of force

that we need in order to tear the atoms apart. If we want to move it even further away from its equilibrium position, the

force needed after reaching rf can decrease again. |

|

|

So if we can apply the force Ff = F(rf),

we will fracture the crystal for sure. Ff thus defines the

ultimate fracture strength of the material. |

|

Easy, but a bit misleading! |

|

|

If you pull at a given material with some external force Fext, you

apply some mechanical stress and this translates into a defined force per bond. |

|

|

Now you double the external force. Does the force per bond double, too? Of course you are

tempted to say, but that is not always true. |

|

Materials that can undergo plastic deformation (all metals and many others) have

a tricky mechanism which allows them to reduce the internal stress by "yielding", by deforming plastically. |

|

|

The strain going with any stress then can be much larger than what we are going to calculate.

You simply never built up enough internal stress to break the material, it first gets longer and longer (and thinner) before

it eventually falls apart. |

| |

|

|

That looks worse than it is. The denominators, the mn products, and theU0

disappear after some juggling, we have |

|

|

| [(n + 1) · r0n · rf

– n] + [(m + 1) · r0m

· rf – m] = 0 |

|

|

|

which finally gives us |

|

|

| rf = r0 |

æ

ç

è |

n + 1

|

ö

÷

ø |

1/(n – m) |

| m + 1 |

|

|

|

A not too involved formula, but not overly helpful either - we have a strong dependence

on the somewhat fishy parameters n and m. Lets see what we can deduce. |

|

|

Lets look at an ionic bond where we have n = 1 and m = 8...12. This gives

rf = r0(2/9 ... 2/13)– 1/7... –1/11 = (1,306...1,185)r0,

or a maximum strain until fracture of |

|

|

ef = (rf - r0)/r0

= (rf /r0 – 1) = (0,306...0,185)

or an ultimate fracture strain of 18% - 30%. |

|

Calculating the force needed for ultimate fracture now is possible, but not extremely

useful. For a first approximation we can just calculate the ultimate fracture stress sf

by using Youngs

modulus

E via sf = E · ef.

|

|

|

In chapter 2.4.1 we obtained

E = n · m ·U0 /r03, and that gives us |

| |

|

sf = |

n · m · U0

r03 |

æ

ç

è |

æ

ç

è |

n + 1

|

ö

÷

ø |

1/(n – m) |

– 1 |

ö

÷

ø |

| m + 1 |

|

|

|

|

That looks like a complicated formula, but all it says is that the ultimate fracture stress

is in the order of 10% ... 30 % of Youngs modulus itself. We will encounter this statement later again, but from

a quite different consideration. |

|

The calculation of Youngs modulus and the

thermal expansion coefficient were quite satisfactory in comparison to actual values.

How good is estimate of the ultimate fracture strength based on bonding potentials? |

|

|

Not very good, as it turns out. In fact, observed fracture

toughness is often quite smaller (like two orders of magnitude) and often materials start to deform heavily, albeit plastically,

but leading to eventual fracture, at much lower stress levels, but much larger strain. |

|

|

The reason for that is that we did not take into account defects

in the crystal lattice. In contrast to Youngs modulus, the melting point, and the thermal expansion coefficient: Fracture toughness is a defect sensitive

property. |

|

|

We must therefore give some thought to crystal lattice defects soon. |

© H. Föll (MaWi 1 Skript)