| | |

12.3.7 Percussion Point |

|

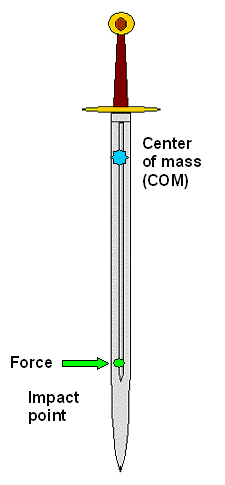

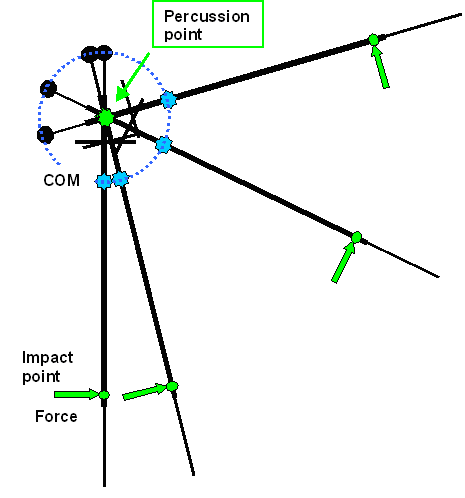

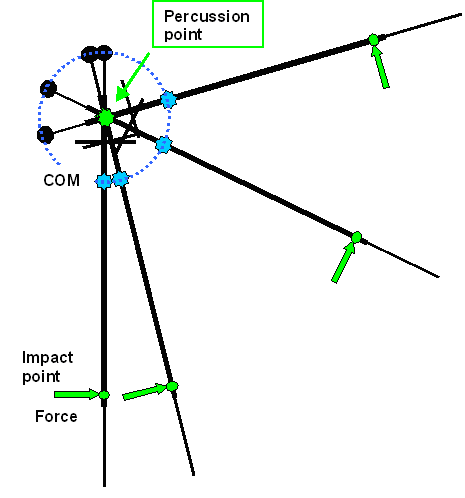

Let's start by reconsidering our "experiment" from before. We hit something and that means applying a force for a short

time to our sword at an impact point. We hit a point well down on the blade

like this: |

|

|

|

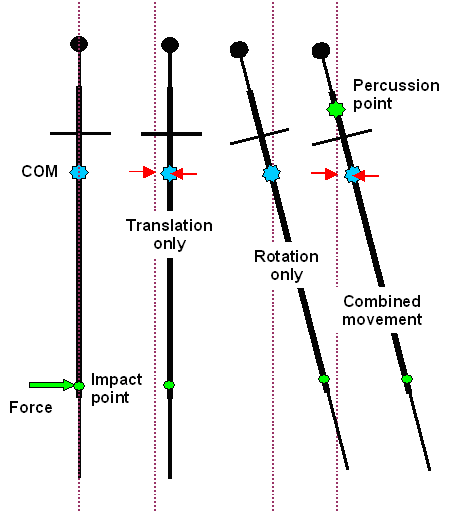

We know by now that this induces:

- A translational movement in the direction of the force arrow.

- A (here counterclockwise) rotation around the center of mass.

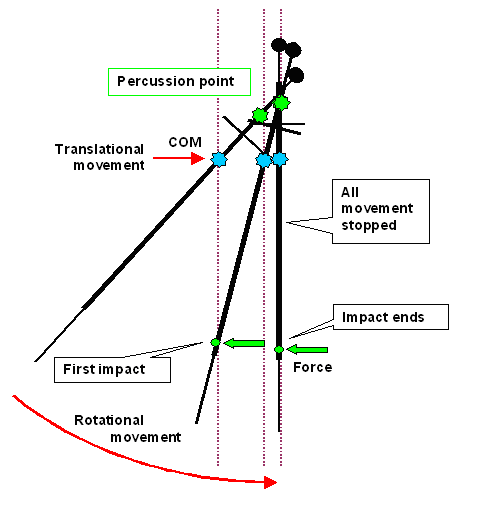

We look now once more on what that means right after the hit, i.e. at a time where the movements are still very small.

What we get looks (schematically and exaggeratedly) like this: |

| |

|

|

| Results of basic experiment and deriving the percussion point |

|

|

|

The translation only (shown with red arrows

at the center of mass) moves the sword a bit to the right. The rotation only rotates

the sword around the center of mass, and the combined movement translates and rotates. Nothing new here.

However, the

drawing shows that there is a point on the hilt, that we now call percussion point,

that has not moved at all. That is so because at this special point, the two movements

cancel. The translation to the right is just as large as the movement of that point per rotation to the left.

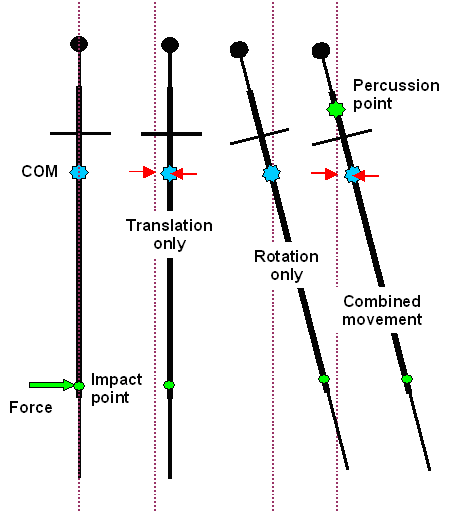

We now

have two special points on our sword: an "impact point"

below the center of mass, and corresponding to this point and only this point, a percussion point above the center of mass. Basic physics tells us that the experiment also works

in "reverse". Make the present percussion point the impact point and you will find that the old impact point is

now the percussion point. Change the position of one point, and the position of the other one changes as well. In other

words: |

| |

|

There is no single percussion point.

Percussion points always come

paired to a pivot point

|

|

|

When we consider a sword we usually talk about its

percussion point, i.e. only one point, and that is always a point down on the blade

and not, as in the picture above, on the hilt. How come? |

|

|

Well, when we consider swords, we hit things with the blade and hold the sword

at the hilt. When we rotate the sword around the percussion point and hit something right at the impact point, we do not

feel forces or torques in our hand because the percussion point that does not experience forces, is right inside our hand.

That is a major statement and we need to look at that in more detail below. But first let's look a bit more on general things.

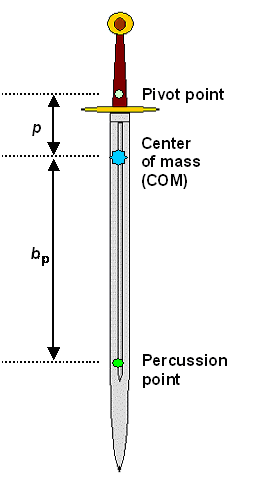

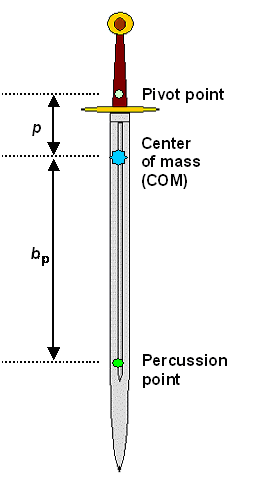

In order to use the conventional nomenclature we now change the naming of the points as follows:

- "Pivot point" = the "point" on the hilt where you

rotate the sword around (the percussion point in the drawing above). Usually close to your thumb and thus cross guard.

- Percussion point = corresponding point on the blade (the impact point

in the drawing above).

We can do that because the two points are completely interchangeable. If you take the upper point as pivot point,

the percussions point is down on the blade. If you would rotate around this point on the blade, the percussions point would

now be at the hilt. Since we rarely do this, the naming as defined above makes sense.

Yes, it is a bit confusing but

not quite as confusing as most of the stuff you read on the Net. Just to make it very clear, here is a picture showing that

plus the two decisive lengths coming with it: |

| | |

|

| Major "points" on your sword |

|

|

Now we have three points on the sword that are of overwhelming importance to its

handling. Let's see why. But first I need to make clear that the most important properties of your sword are

- its mass m, and

- its moment of inertia

I relative to the center of mass. This concerns the distribution of the mass in space and this is determined

by the basic geometry that also determines the position of the center of mass (one of

our three points in the drawing above).

When we now start to consider how to optimize a sword for actual sword fights, it is good to realize that you do not

have much choice with respect to the mass. Your sword should be as heavy as it can be considering that you

must be able to handle it for some time. The mass thus is a very personal thing but given within narrow limits like

0.8 kg - 1.5 kg..

The basic geometry is also your personal choice. You want it long or short, straight or curved, slender

or broad, for whatever reasons of your own. OK - that defines the basic geometry to a large amount. Now the "fine-tuning"

starts. |

|

|

Realizing that the pivot point is rather fixed (close to the cross-guard), you

are now looking for getting a good position for the center of mass and the percussion point of your sword. These parameters

are now the most important properties of your sword after you picked mass and basic geometry (always assuming you use your

sword for actually fighting and not just for showing off). Why? |

|

The position of the center of mass relative

to the pivot point, together with the moment of inertia, is crucial for the handling as far as rotations are concerned.

You want it relatively close to the hilt but not too close because that prevents to have a good location of the percussion

point and the ability to deliver large energy on impact. |

|

The position of the percussion point is probably the most important parameter.

You want to hit your target close to this point because then you don't feel jarring forces in your hands that tire you quickly

if not breaking your wrist. You also deliver substantial or even maximum impact energy.

Obviously you want the percussion

point not too far from the tip of your swords because there is sense in having a long blade if you need to hit targets on

a point way up on the blade. |

|

|

Nothing helps. We need to figure out how to find the position of the percussion

point (relative to a pivot point on the hilt). For a given sword there are two ways for doing that:

- Calculate the percussion point position.

- Find the percussion point position by some experiment

The Science link shows how to do the basic calculation. It's actually easier than the calculation for the center of mass or the moment of inertia.

In essence, we want to calculate the distance b between the center of mass position and the percussion point

position as shown in the drawing above.

How you can find the percussion point experimentally

is explained here | |

|

|

What theory gives us are essentially the following rules:

- The distance b between the center of mass position and the percussion point position is directly

proportional to the moment of inertia. Since we tend to keep the moment of

inertia small, this tends to move the percussion point "up", i.e. closer to center of mass.

- The distance b between the center of mass position and the percussion point position is inversely

proportional

to the mass m. Reducing the mass thus tends to move the percussion point "down". However, reducing

the mass also reduces the moment of inertia and that moves the percussion point "up". Both effects tend to cancel

each other.

- The distance b between the center of mass position and the percussion point position is inversely

proportional to the distance p between the center of mass and the pivot point. Making this distance

smaller / larger moves the percussion point down / up on the blade.

|

|

Where does that leave us? Can we produce a sword with a given mass and a basic general geometry and then

adjust the the position of the percussion points (or center of mass point) while not changing the position of the others

by some fine-tuning of the shape? The answer is simple |

| |

|

|

|

Make a change to some parameter - the length or width of the blade, the tapering

of the blade, the weight of the pommel and so on - and you change the moment of inertia, the position of the center of mass,

and the position of the percussions point (for the given position of the pivot point).

Optimizing your sword is not

an easy thing, in particular if you consider that there are two more points - the nodes

of the second-order oscillations dealt with in the next sub-chapter) - that should have special positions. |

|

I will get to that in more detail later. For the time being we just note that

medieval or older swords are often wonderfully optimized with respect to all these parameters, while some of the modern

replicas, looking pretty much like the original, are rather bad. What that tells us is: |

| |

Optimizing your sword means:

Details matter!

|

|

| |

| |

| |

Working With the Percussion Point |

|

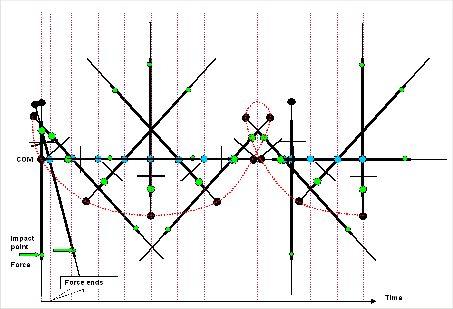

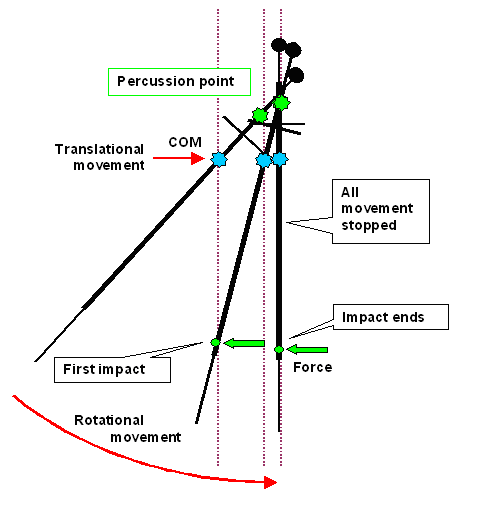

Look at what I had called the "basic experiment

to derive the percussion point" again. Something is hit by a sword at the "impact point", later called

percussion point". Or is it?

Simple pictures are often deceiving (while sophisticated pictures are incomprehensible).

I see a sword at rest impacted somehow by a force. No hitting there. The next picture

goes with that interpretation. The sword, originally at rest, starts to move in a combination of a translation to the right

and a rotation around the center of mass.

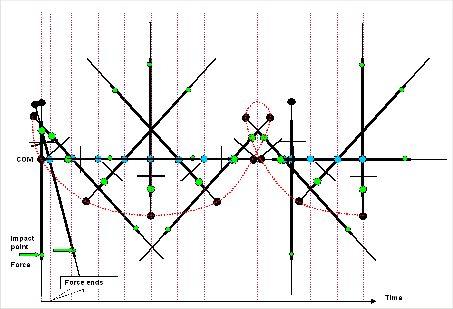

It is quite illuminating to look at this more closely. The picture below shows what happens: |

| |

|

|

| Movement of sword (in outer space) upon a short impact |

|

|

The sword increases both velocities - translational speed straight to the right

and rotational velocity around the center of mass - as long as the force lasts. Then it keeps moving with whatever velocities

it acquired, spinning and moving forever. The red dotted line traces the movement of the pommel to give some idea.

if

we wouldn't be in outer space but on earth, the sword would do exactly the same thing plus

falling down with increasing velocity downwards (while still doing its spinning and moving to the right) until it hits

the ground. The center of mass would run on a downwards (parabolic) curve. |

|

|

Note that we only have a "pivot" or "percussion"

point, a point that doesn't' move at all, for the first moment of impact. |

|

Now, for contrast, let's look at the case where the force is there for some time

and always at a right angle to the blade. We have a constant torque in other words. What happens then is shown below |

| |

|

| Movement of sword (in outer space) for a constant torque |

|

|

Interesting, isn't it? The sword moves in a circle with the apparent center of rotation being the percussion point. We have

a pivot point rotation, in other words. It is still a rotation

around the center of mass plus a translation of the center of mass. The translation is not just to the right as before but

changes directions all the time since the force changes its direction all the time too.

Now you see the full meaning

of the "percussion point". As long as the torque is on, it won't move. You also see why the percussion point is

sometimes called "center of oscillation". More to that here |

|

|

What happens if the torque stops? Exactly the same thing as in the first case except that

the sword will now fly off (spinning all time) in the direction its center of mass was moving at the moment the torque stops. |

|

|

What happens if we come back from outer space and turn gravity on? Well - the sword falls

down. You probably could have guessed that. We can prevent that if we "nail down" the percussion point (now better

called pivot point) as described before. The nail or better rotation axis then

exerts a force (and feels a force; actio = reaction to quote Newton to the cognoscenti here) that exactly cancels the gravitational

force pulling down. |

|

This was possibly helpful but certainly needed. Now we will finally hit something

with our sword. I need to distinguish tow (extreme) cases:

- Very shortly before impact you completely release your sword. Your body, arm and wrist movement stops and you open your

fist. I know you can't do that perfectly but you should try. I have no problem doing that in my brain and then writing down

what will happen.

- You stick to your sword and you try to keep it moving at the impact moment.

The first case we have already dealt with. It may come as a surprise but in simple mechanics (what we are doing here),

time is reversible. All calculations work just as well in reverse. If you make a movie of some calculated movement, nobody

could tell if you run it normally or in reverse.

All we need to do then is to run the picture from

above in reverse. I will only show the final scene just before impact. For varieties sake I reverse the direction. Here

goes: |

| |

|

|

| Sword hitting something |

|

|

|

I assume that the sword impacts the target at the first dashed line and then cuts its way

inside until it comes to a full stop. And that's indeed what would happen. The force put up by the target would last as

long as needed to stop all movement. If your hand was just about "hovering" over the grip,. it wouldn't feel much

since the hilt around the percussion point is not doing much during impact.

That was cutting for some distance into

a relatively soft object. Now let's consider what happens if you hit a big stone. The distance for stopping the movement

then gets rather small, so all we have to do is take off the two dashed lines on the left as well as the force arrow on

the middle positions. The sword then must stop all movement instantaneously. ???? |

|

You know that can't be true. Your sword will fracture, bend, kick back like crazy

or do other unwelcome things but it will not just stop with your hand not feeling anything at the hilt. I agree. Nevertheless,

theory tells us unambiguously that rigid

bodies do just that. And that was the assumption behind all the "theory" so far. We are dealing with

rigid bodies, things that do not deform or break or have any internal properties. There are no rigid bodies in nature but

doing theory with real bodies is just far messier if not simply impossible. A good steel sword, however, is an almost

rigid body under many circumstances and that's why we can use that approximation in many cases. |

| |

|

Rigid body theory is actually pretty good as long as the bodies in question do not experience

forces that more or less destroy them

That, however, is what happens if you hit a solid rock forcefully with your sword.

Hit it hard with the percussion point or in any other way you like. You probably have a good feeling of what is going to

happen without doing any calculations and you certainly will not like the result. |

|

Let's look a the second case. You are still attached to your sword and trying

to keep it moving. Imagine you swing your sword with closed eyes. You don't know when you are going to hit something and

just keep swinging to with all you have. Now we have three problems:

- You are definitely feeling something in your hands and body at impact. After all, the sword by itself might have come

to a smooth stop if you found the percussion point, but that doesn't apply to your hands and body. That needs to be stopped

too and that needs some force.

- All calculations for the percussion point and so on are no longer fully valid because parts of your body are now parts of the system.

- Taking that into account is difficult to impossible because you do not have an almost

rigid body (like your sword). We would need to use the "slime bag" approximation and that is notoriously very

difficult.

|

|

One last topic needs clarifying. We always consider pivot points at the hilt and

discuss what you will feel in your wrist when you hit something. Hitting things at the percussion point is favorable because

it minmizes forces to your wrist. All of that is true. And yet, the apparent center of rotation for many movements is not

at the wrist but closer to the elbow, as shown here, for

example. Shouldn't we consider pivot points further up and jarring of the elbow? |

| |

|

No, we shouldn't. The reason for this can be found in the old "beam bending" science modules. The force acting on the impact point tries to bend the

blade and that implies that forces and in particular torques "travel" up (and down) the blade, producing some

(small) elastic deformations. And these forces and torques is what your wrist will feel, no matter where the apparent center

of rotation is situated. You elbow might feel it too, but will notice it less because this joint is just much stronger than

the wrist. |

|

All things considered, having an optimized percussion point position on your sword

is a good thing. It won't do miracles, however. For all the reasons considered here and

because we need to add the next point: vibrations of sword before we can discuss final optimization . |

| |

| |

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)