Luristan Swords

IMAS 1

Luristan Swords |

IMAS 1 |

| Note: The “Lurtistn Sword” paged will be formatted somewhat differently (simpler) than the rest. As I grew older, my eyes deteriorated to a point where I can just barely type stuff in my html editor. I apologize for typos and perfectly spelled but wrong words produced by the erroe correction without me noticing. |

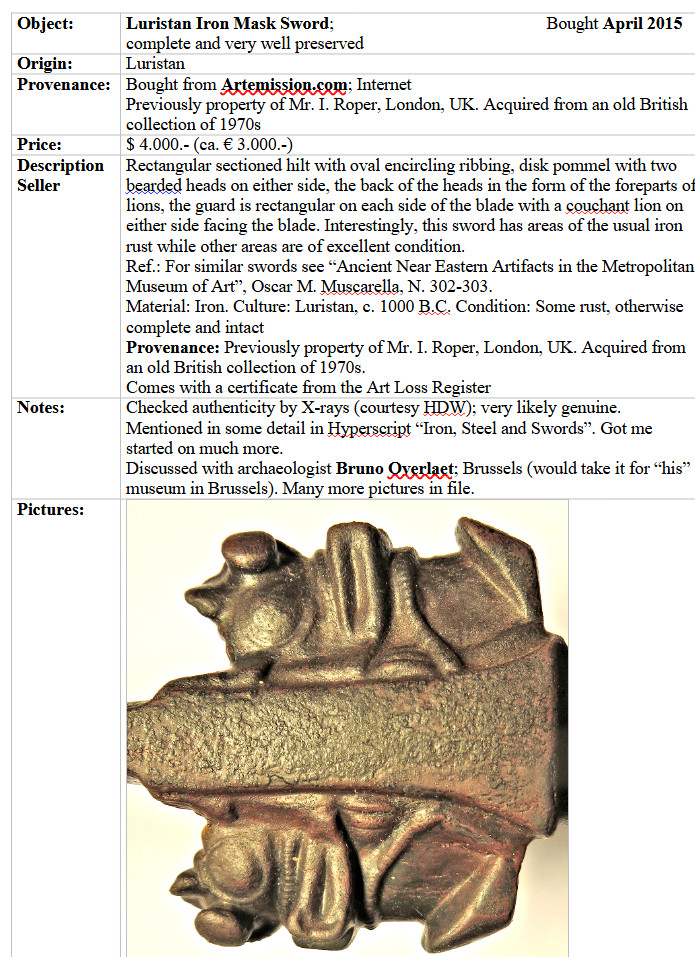

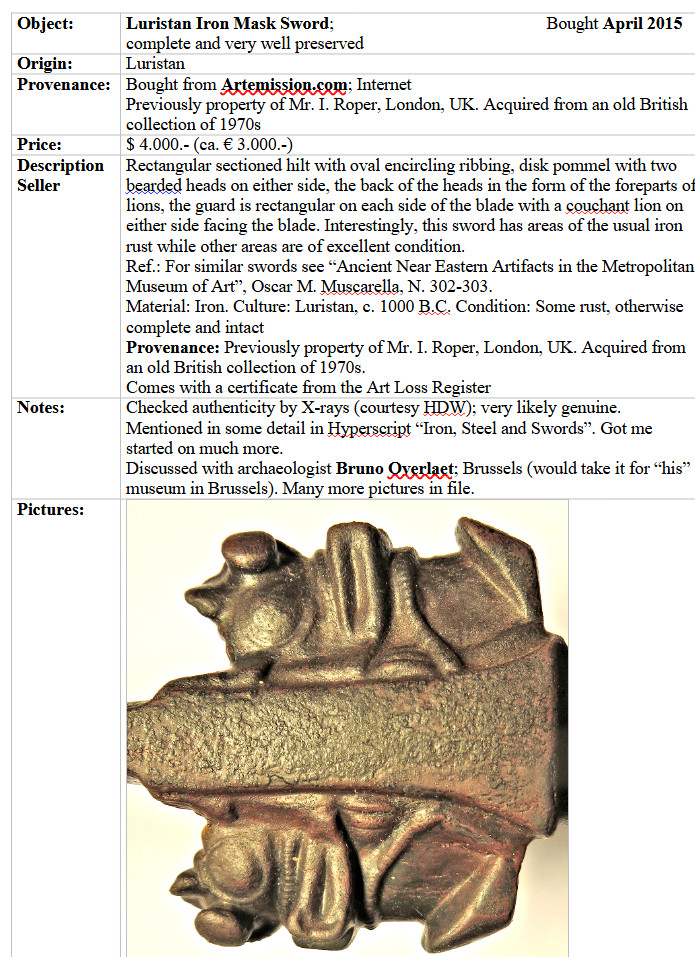

| My internal notes after buying the sword |

|

|

Detailed Observations made in 2025 | ||||||||

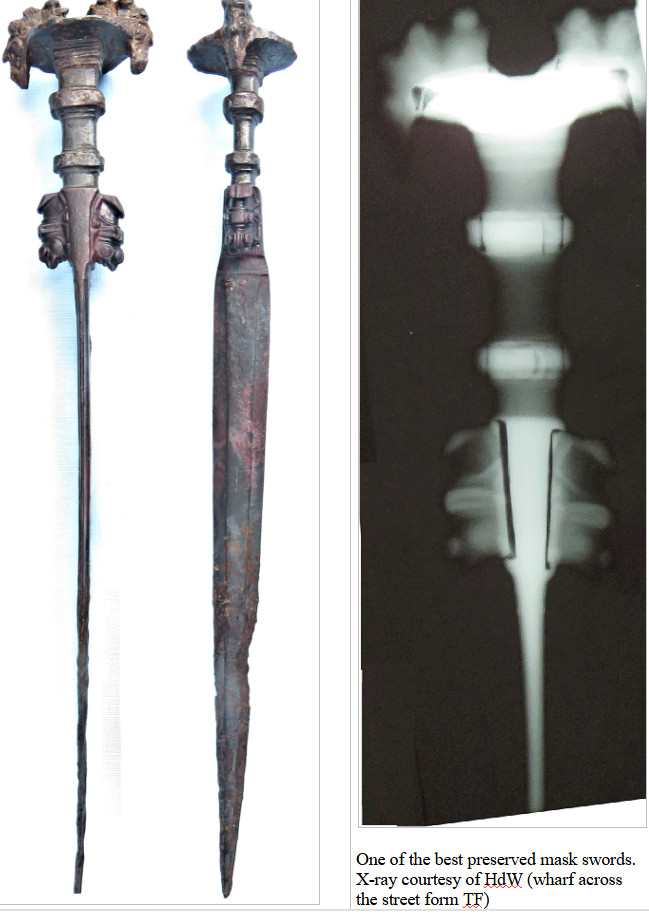

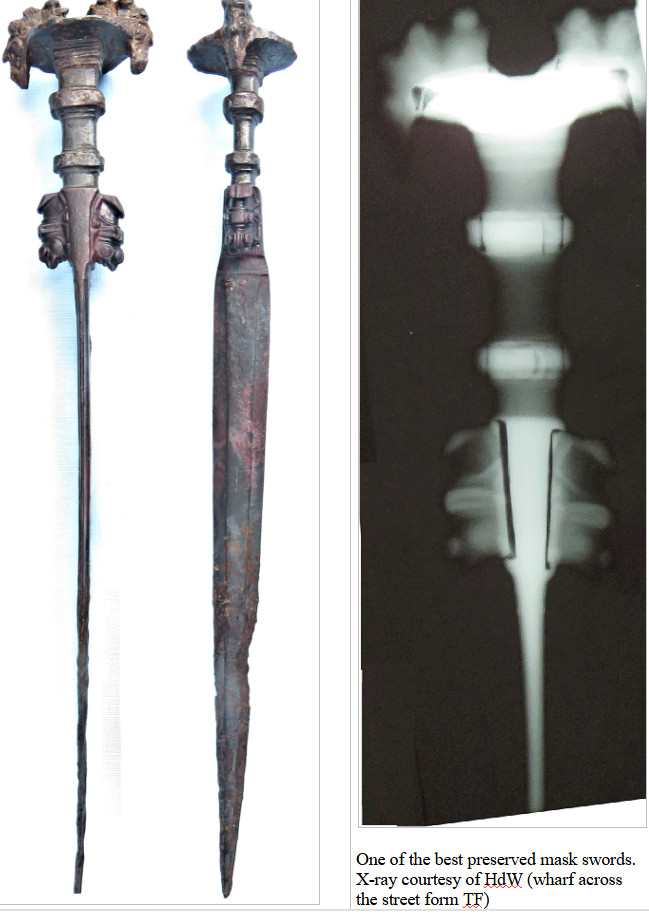

| MAS 1 is our old friend from the “More

Luristan Swords” module in the illustration section of chapter 11.1. It is rather well preserved with the “animals”

and a large part of the blade hardly corroded at all. I shall first point out unexpected peculiarities of features that

look perfectly normal at first sight. The Blade. It has the unique shape of almost all of the Luristan IMAS swords (and some others): a thick section or mid rip in the middle and thinner parts towards the edge. A typical cross-section for swords / daggers intended primarily for thrusting, one is tempted to say. Yes, maybe – but how do you forge a blade like that? From some lump of low-quality raw iron? With primitive tools? A contemporary smith may laugh at this question but I simply see problems. You certainly need a good anvil for hammering out the rather sharp ridge between mid rip and the outer parts of the blade. Whenever you bang on one side, you automatically do something to the other side resting on the anvil. That is true for all blades, of course, but I would guess that the problem is far less severe for flat blades, or blades with a fuller. Maybe the old Luristan smiths formed the general outline of the blade by piling cut-to-size sheets on top of each other and then fire welded the package? I’ll get back to this farther down. |

| |||||||

| Corrosion Patterns

A heavily corroded blade usually looks like a mess with a chaotic surface lacking some specific structure. Well – not true for IMAS 1 (and others). Here we find some corrosion features that provide for some thought, namely: | ||||||||

| Well-defined “missing” sheets.

At several places corrosion removed a thin layer of the iron, leaving a flat surface below. Here is a picture from around position 15 on the A-side: | ||||||

| We see similar missing layers at a few more sites and in particular right at

the edge of the blade. Other swords also show this peculiarity. Corrosion can produce all kinds of patterns, so one such

occurrence is not remarkable. But if you see this feature at different parts of the blade, it stands to reason that the

corrosion pattern follows some interior pattern of the iron, or a layered structured in plain words. How thick were the

missing layers? Around 1/10 mm, I can say. Does this mean that the Luristan smiths forges out sheets just 0.1 mm thick and then fire-welded a pile of them to the desired shape? Certainly not – although they did produce thin sheets as we shall see. My best guess s that they used extensive faggoting for making sheets in the mm thickness range. Theses sheets would contain many rather thin layers The somewhat dirty interface with local stress ans strain between the individual iron layers allowed for local corrosion in some places. I will come back tho thi |

| |||||

| The blade was not sharp IMAS 1 is well enough preserved to allow a look at the edge of the blade. It is more than 1 mm thick! Maybe slightly rounded but a far cry from being sharp. You hardly could cut custard with this blade. The picture on the right shows this (around 1.5. mm thickness). And no, this was not caused by corrosion. In a stereo microscope you see so much more than what can be caught in a picture, and looking along the edges of the well preserved blades makes absolutely clear that they were never even close to being sharp. The unavoidable concision is that these swords were not meant for use. A lot of fancy sword throughout the ages were not meant for use either but were nevertheless quite sharp and fully functional. A four wheel drive SUV Porsche is not meant for driving around in the mud either, but perfectly capable of doing so. No such pretensions with the IMAS. Most likely the owner didn’t even wear it as part of his costume. It would have been awkward to wear anyway: With the blade flat on your body, the figures on one side would be poking into you body! |

| |||||

| Wormholes Along the Mid-Rip Ridge? Roughly at the position where the blade corrosion starts, (around position 16) there is a strange kind of structure termed “wormhole” by me. It runs along the ridge formed by the mid rip and the thinner part of the blade. It is particularly prominent on the A-side but traces of wormholes can be found on all 4 ridges. So far I have not seen something similar on other IMAS or in the literature. The wormhole seems to be etched into the iron and has a diameter of about 0.8 mm. Here are a few more pictures:

|

| |||||||||||||

| What the f*** is this! Excuse my Trump but these structures are something never seen before on old iron artifacts. What could it be? Let’s go through the list | ||||||||||||||

| 1. Something the smith did while forging the blade? Most certainly not. I can not think of any reason why a smith might have wanted to do this. Not to mention: how would he do it? Let me know if you could produce such a feature. 2. Something some modern guy did in an effort to clean / restore the blade? Once again: how would you do it? Running a 0,8 mm drill bit (or some other tool like that) along the edge would not produce that pattern. 3. Some tiny worms crawled down the sheath (IMAS came with sheaths), got stuck in in the tip area, died, and while decomposing their body fluids etched the iron, producing a “negative” of their body structure. Sounds crazy, is crazy but the only explanation I can come up with so far. Let me know if you have a better one. |

||||||||||||||

| Connection of Blade and Hilt | ||||||||

| The first question is simple but not easy to answer: Is the major body of the hilt and the

blade one piece of iron? Or is the blade just somehow connected to the hilt as seen in some of the “old”

X-rays? The X-ray picture of this sword suggests one piece, but I can not be sure. The second question is: What is the detailed structure at the meeting of hilt and blade? Here is a picture |

||||||||

| ||||||||

| The mid rip flares out or gets wider, the blade itself flares “in” or narrows somewhat.

A thin “scalloped” kind of belt or collar encircles the blade at a point where the mid rip is almost as wide as

the blade. From about the point where the blade starts to get narrower, it also starts to get thicker and when it finally enters the hilt a few mm above the “belt”, its thickness defines the beginning of the hilt. The whole thing is quite elegant and attractive and must have been rather difficult to make. It seems to serve no other purpose as to look good. | ||||||||

| The “Animals” | ||||||||

|

| |||||||

| What is it? Certainly nothing that you find in nature and nothing you find in

other pieces of art anywhere on the planet around 1000 BC give or takes few hundred years. The beast carries something on

its back, possibly with a blanket or something with fringed edges under the load and has clawed feet (not hooves) If the round structure at its head are its eyes (they resemble the ones of the human head) the extensions on its head are – well, some protrusions. If the extensions are the (stalky) eyes, the round things are what? Could it bet hat the artist couldn't do better and the animal is just a primitive poor expression of something the artist tried to make but failed? Not likely. After all, the human heads are quite good. We must conclude that the artist wanted these beasts to look this way. Now to the big question: How were these figures made? Definitely not by casting: First, nobody could cast iron then, and second, the micro structure, if analyzed clearly shows that no casting was involved. Forging the figure just with a hammer and an anvil (plus a few special tool, maybe) can be ruled out, too. You just can not work this way with the precision and details we find. Hammering some piece of hot iron into a die is the third way that has been suggested but was definitely not used. First of all, with the concave parts encountered, you couldn’t get the figures out of the die without destroying the die. All figures are originals – quite similar but different – so you would have to carve a die for every figure anyway. But that makes no sense. Before you spent a lot of work and effort to carve the (negative image) die from a necessarily very hard material, you far more easily carve the iron directly. You may forge an approximate shape with your hammer, but you must carve the details. For that you need not only special tools but also a suitable lump of iron. It should not contain large inclusions or very hard pats |

||||||||

| Maybe we learn more as we look at other IMAS and at the renderings of the animal as part of the head of the other figure. | ||||||||

| Fixing the Animals to the Hilt | ||||||||||

| It’s done by “crimping” as defined in the pictures below | I added more to that later at the end of the text | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| It looks very much like the smith generated a depression in the massive hilt material, inserted

the figures, and “crimped” then in place. No, he didn’t Scroll down to find out how

I arrived at this conclusion long after I have written what follows.

Yes – but there are many questions: 1. Why the bad fit with lots of open space below the figures? These guys could do better than that. Maybe they only cared for perfection were it could be seen and cut corners when doing invisible part? Or they used a technique, as we shall see, that automatically produced this empty space. 2. Was the outer rim of the “crimp” fire-welded to the figure.? That would mean fire welding on a very small and sensitive scale. 3. However it was done, how could the smith make the surface look so perfect! Figure and hilt merge perfectly, there is not the slightest sign of looking at two separate pieces. At the minimum you need good files or other grinding technologies to smooth everything so perfectly. 4. What kind of iron was used? Doing precision work on a sub-mm scale certainly demands homogeneous iron, not brittle, and with halfway constant properties throughout. That is not what was directly available. It follows that the smith must have had some way to “collect” the right iron from his sources. | ||||||||||

| We will get more input to this question when we look at other MAS so I stop at this point.

Good questions - but by now I found the answers! Farther down most of this will be explained. |

||||||||||

| The Bands Around the Grip

All IMAS (and related blades) feature two rings around the central part of the grip. There must be some meaning to this. Of course, it would provide for a better grip if you intended to use the weapon (which nobody ever did) but this could have been achieved far easier (i.e. by a leather wrapping or by many other means found on hilts everywhere. The rings are either directly welded on or, as in the example on the right, embedded in a wider ring and held in place by crimping once more. |

|

| |||||||||

| Once more: An unbelievably perfect job of crimping and fire welding has bee done. I would

tend to believe that it is not easy to weld the ring around the handle and then weld the two ends of the ring together.

Once more, we encounter fire welding on a mm scale. I I'm not a smith and it could well be that an experienced smith would laugh at my concerns. We certainly need to consult one if we want to get closer to the secrets of the ancient Luristan smiths. |

|

| |||||||||

| Structures Below the Top Disc Some IMAS sport some decorative structure below the top disc. Most, however, don’t. The pictures show some examples; more will come in time. The IMAS displayed in the Louvre, Paris, is quite similar to my IMAS 1 How is the decoration made and fixed to the sword? |

|

| |||||||||

| The big big picture below from the “cut sword” shows “crimping” with crimps form the grip part and the disc part. That is not something easily done. The X-ray picture of IMAS 1, however, does not show crimping or some other structure. That might be accidental. No free space will be seen if the alignment of the sword is not right. |

|

| |||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Head of the “cut sword” (IMAS 8). The decorative structure below the top disc is a kind of ring that is “crimped on”. Crimps were made in the material of the grip and on the disc. Once more there is no tight fit of the ring to the body f the grip: If thee crimps were fire weed to the structure needs to be determined. | |||||||||||

| The “Heads” | |||||||||||

| The heads sitting on the pommel disc consist of two parts: A bearded guy, sort of hanging over

the edge of the pommel disc, and the front part of the “animal” coming out of the back of the head of the guy

and looking towards the center of the disc. Once more, nothing like that has ever been found elsewhere. You may claim that we have plenty of bearded guys: Assyrian, Celts, you name. And yes, all bearded guys do look alike to some extent but stylistically they are quite different to the Luristan chaps. The X-ray above also shows that the heads were crimped-on. Once more with utter perfections as seen from the outside and without perfection for the invisible inner part. |

|||||||||||

The Epiphany – How the Old Luristan Smiths Used the Crimping Ring | ||||||

| Before I had my epiphany, I have already figures out that the smiths used what I called a “crimping ring”. This is details in the module “IMA 5” which you should d consult before reading on. The essence I repeat below. | ||||||

| First, the smith makes what I like to call a crimping ring.

The sketch below gives an idea of what I mean. The underside of the ring is then fire-welded to the bulk and the “black

lines” in the X-ray picture denote the empty space inside of the crimping ring. From IMAS 5 |

| |||||

| Next I observed that the IMAS 2 sword showed some structure –

part of the animal anatomy – in what I had identified s the crimping ring material. While wilting for hours in a hospital

waiting room, I considered was what that might imply and how to find out. The answer was: Compare the X-ray picture with

the actual object1 Here is is: | ||||||

| ||||||

| What do we see?

1. The X-ray picture clearly shows that the animals have a flat bottom while the hilt shows some elegant curvature. 2. The black space between the animals bottoms and the hilt material comes about because there is less material in the way of the X-rays. That is easily understood since the bottom part of the crimping ring dos not cover thew whole hilt. In consequence, one side of the black space delineates the surface of the hilt (outlined in red), whereas the other side depicts the underside of the animal. 3. Everything above or below the red lines thus is not part of the original hilt but either part of the animal or the side wall of the crimping ring. 4. The crimping ring part must extend to a height roughly indicated by the blue line. 5. It follows that the out side of the crimping ring was elaborately carved into the stricture we see: The curving part of the hilt and the bottom part of the animal We are forced to conclude that the old Luristani smiths used the crimping ring in a complex and admirable way. They first welded it to the hilt, then inserted the animal, fire-welded the rim of the crimping ring to the animal, and then carved the whole structure to what we still can see. Thar must have taken incredible skill and possibly more then one expert to do the work. But now let’s step back and consider: How would one produce the structure of IMAS 1 (or many of the others)? You (or your partner) has made the animal and now it needs to be fixed to the hilt in such a way that you get what you see in the pictures above. Make somehow a depression in the hilt, insert the animals and fire weld it? Won’t work. Not only can you not get the elegant curvature for the bottom part, but you would damage the animal. Fire welding needs some serious banging on the parts and that would necessarily deform and damage the animal (or the heads on the pommel). You also would not be able to get that flawless and intricate exterior. The use of a crimping ring as described above is about the only was to achieve all your goals. It just demands very high skills in using your hearth and hammer. Of course we must ask ourselves by now if this crimping ring technique was also used to fix the heads to the pommel, the rings to the grip and the sub-pommel decorations (if used) to the hilt. If we look at the total X-ray picture again, we realize that this is likely. | ||||||

| ||||||

| The rings around the hilt do show the empty space structure, hinting that crimping

rings were used. The pommel is too massive to show much internal structure; we only see some “empty” space behind the persons chin / beard. I refrain from speculating how that could be interpreted but I’m rather sure that the old smith has used some crafty way to attach the head / animal structure tot the pommel. To summarize: As it turns out by now, making an IMAS was far more complicated than envisions so far. The makers (I would assume that at least two persons were involved) needed to have incredible skills in dealing with rather bad quality iron / steel. I doubt that any smith living right now could produce an IMAS replica without extensive practicing. This sword must nave been incredibly valuable in their original context some 2.800 years ago in the high mountain regions of Luristan. Why and how the IMAS ended up in rather indistinct graves, in a rather desolate area that shows no traces of some advanced civilization, is a mystery to me. | ||||||

![]() First Iron Swords - Luristan Type 1 Iron Swords

First Iron Swords - Luristan Type 1 Iron Swords

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)