| | |

Early Places With Metals:

|

| |

|

|

Yumuktepe is a tell or ruin mound right in the thriving

city of Mersin in Southern Turkey. It raised itself by continued settlements since

7000 BC until the Middle Ages. Yumuktepe was close to the coast when the first people settled there. Now it is about a mile

inland. |

|

|

Yumuktepe thus is far younger than the other old settlements covered in this

module (look a the time line to get an idea). Its present claim to fame is that

so far it yielded the oldest smelted copper known

to archeometallurgists.

I visited Yumuktepe in Sept. 2013. While I can't give you a picture of the "oldest smelted

copper", I can give you a vague idea of what "finding" up to 9000 year old things actually entails: long

and hard physical work after a long and dedicated study of the scientific background. |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| Yumuktepe from above |

|

| | |

|

|

|

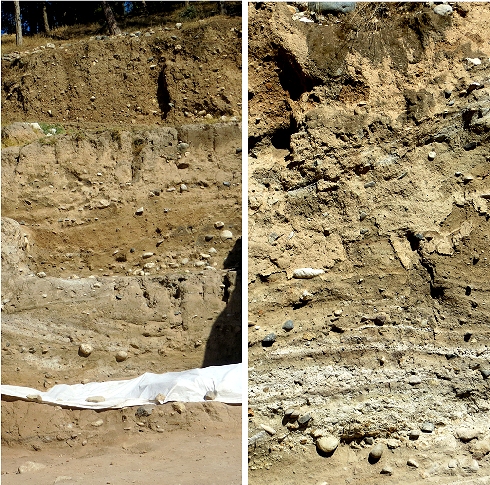

Looking down from the hill top we see the remains of trench dug by the British

archaeologist John Garstang in 1937 - 40 and 1947 - 48. John distinguished 33 different cultural levels. While his "stratigraphy"

has been augmented and differentiated in more recent times, it is generally correct and still used. The lowest and thus

oldest level (No. I) has meanwhile been carbon dated to about 7000 BC, the No. XXXIII

top level is from the Middle Ages. Archeologists give numbers in Roman numerals, of course! |

|

What some of these levels look like can be seen here: |

| | |

|

|

| | |

|

|

It is not all that easy to make sense of what you see in such a vertical cut. Personally,

I have no idea of what one can see in those pictures, except that the weighted-down plastic coverlet in the left-hand picture

signals that this is a "live" excavation and that you should not touch anything.

Indeed, since 2000 Isabella Caneva of the University of Salento / Italy resumed digging, and some of what I'm

recounting here is from Isabella Caneva's article about the subject 1) and Ünsal Yalçin's article about the copper investigations.

What you might see under one of those plastic covers is something like this: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

|

What you don't see are metal artifacts. First, there are far fewer of those in

the mound than pot shards, and second, you have to sift through a lot of dirt and look rather closely to find one. Small

copper needles or beads don't look like much since they are heavily corroded and mud-encrusted. Not very impressive. That's

probably also why old metal things are not displayed in the Mersin museum (or in most other museums I know of).

Here

are objects from Yumuktepe that are displayed in the Mersin museum: |

| |

| | |

|

| About half of the Yumuktepe objects displayed in the Mersin museum |

|

| | |

| |

|

| Yumuktepe "Vase" |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Pottery dominates, of course. It ages well (i.e. not at all) and the experts can tell from

looking at a pot(shard) from which period it is. Unfortunately, Turkish museums typically won't tell. The explanation given

for the pretty object above (and for some below) is included in its entirety. |

|

People throughout the ages could be relied upon to provide at least two things:

- Jewelry and other means to adorn bodies.

- Toys for kids.

Both items have many merits on their own but also tend to make life easier for the males of the species. They promote

peace and quiet. |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

| |

|

Note that besides the ubiquitous white bone beads, "greenstone" is prominent once more. |

| | |

| |

|

| Little pots used as toys for children. |

|

| | |

|

|

I almost forgot: you typically find stone tools in stone age settlements! Here

are some not-so-perfect obsidian tools found at Yumuktepe. |

| |

| |

| |

| | Tools made from imported obsidian |

|

| | |

|

|

It is time for the climax: |

| | |

|

|

|

Copper artifacts found in layers XVI

(around 5000 BC) were made from

smelted copper that was cast

|

|

| | |

|

|

|

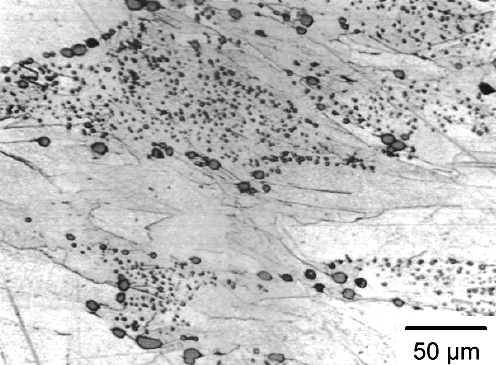

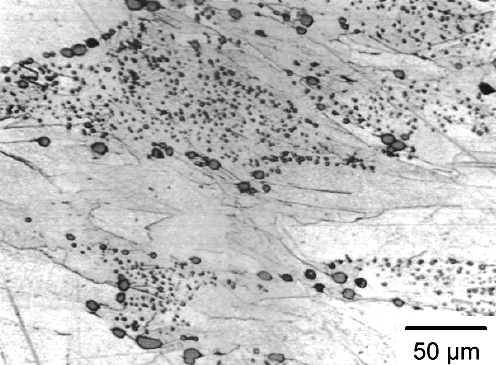

That was proved beyond doubt by an extended metallurgical analysis performed by Ünsal Yalçin, after he was allowed to re-examine these artifacts around

2000.

Ünsal Yalçin based his analysis not only on the rules for interpreting microstructures discussed before but mainly on the prominent copper oxide precipitates found in the copper

plus the trace amounts of various impurities not normally encountered in native copper. Here is an example. |

| | |

|

|

|

|

Microstructure showing a Cu - CuO2 eutectic

- irrefutable evidence for smelted copper! |

| Source; Ünsal Yalcin; with

friendly permission |

|

| | |

|

|

|

The dark objects are CuO2 precipitates. The grain structure indicates deformation

and beginning recrystallization due to annealing. |

|

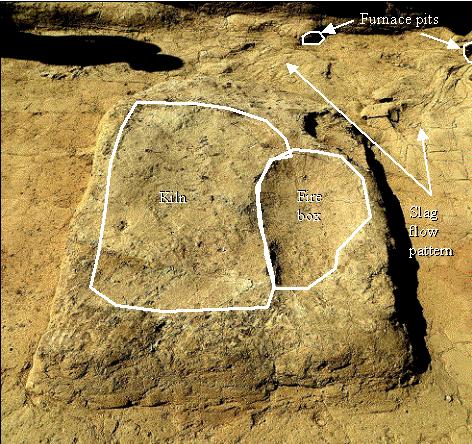

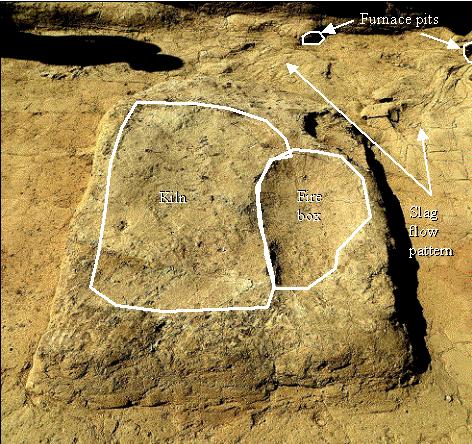

Last, some tantalizing pictures I took. They must be from a layer younger than

5000 BC, from a time and when smelting was "routine". What I believe I saw - and this might be completely wrong,

mind you! - is a "pyrotechnology" workshop with a kiln and two smelting furnaces: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| Pyrotechnology workshop |

|

| |

|

|

|

All that's left of the kiln is a raised platform (possibly built on mudbricks; those were

around in other parts). Then we have two small (ca. 25 cm) shallow bottom pits left over from shaft furnaces, and the flow

pattern of slag "imprinted" on the floor. |

|

| |

| |

|

| Flow pattern of slag from the (marked) furnace bottom |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Actually, Isabella Caneva, who I contacted later, not only granted me permission to use these

pictures but affirmed my guess. What we have is actually a platform inside a Late Chalcolithic élite building of

level XV, 4500 BC. Here is another picture of such a workshop that Isabella gracefully let me have: |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

Late Chalcolithic (4500 BC) metal workshop in Yumuktepe

Large size |

| Source: Provided by Isabella Caneva; Thanks! |

|

| | |

|

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)