| | 1. Introduction

|

| |

1.1 Why Oh Why? |

| | 1.1.1. What it is all about

|

|

When I worked on the Hyperscript "Iron. Steel and Swords" I run across some "old" literature (from around 1930, say)

containing very interesting metallographic studies of old swords. Unfortunately, the pictures in the papers as found in

the Net typically no longer contained much information. They had faded to some grayish smears.

The reasons for that

are clear. Some hard-working soul, after much specimen preparation and surface treatments, had finally produced a clear

picture in some microscope (a "micrograph").

The photographic negative (an "analog" thing) contained many megabytes (MB) of information. In other words: In a dark room you could print it onto poster-sized photographic

paper hat still looked crisp and contained a whole range of grey levels between pitch black and brilliant white.

|

|

|

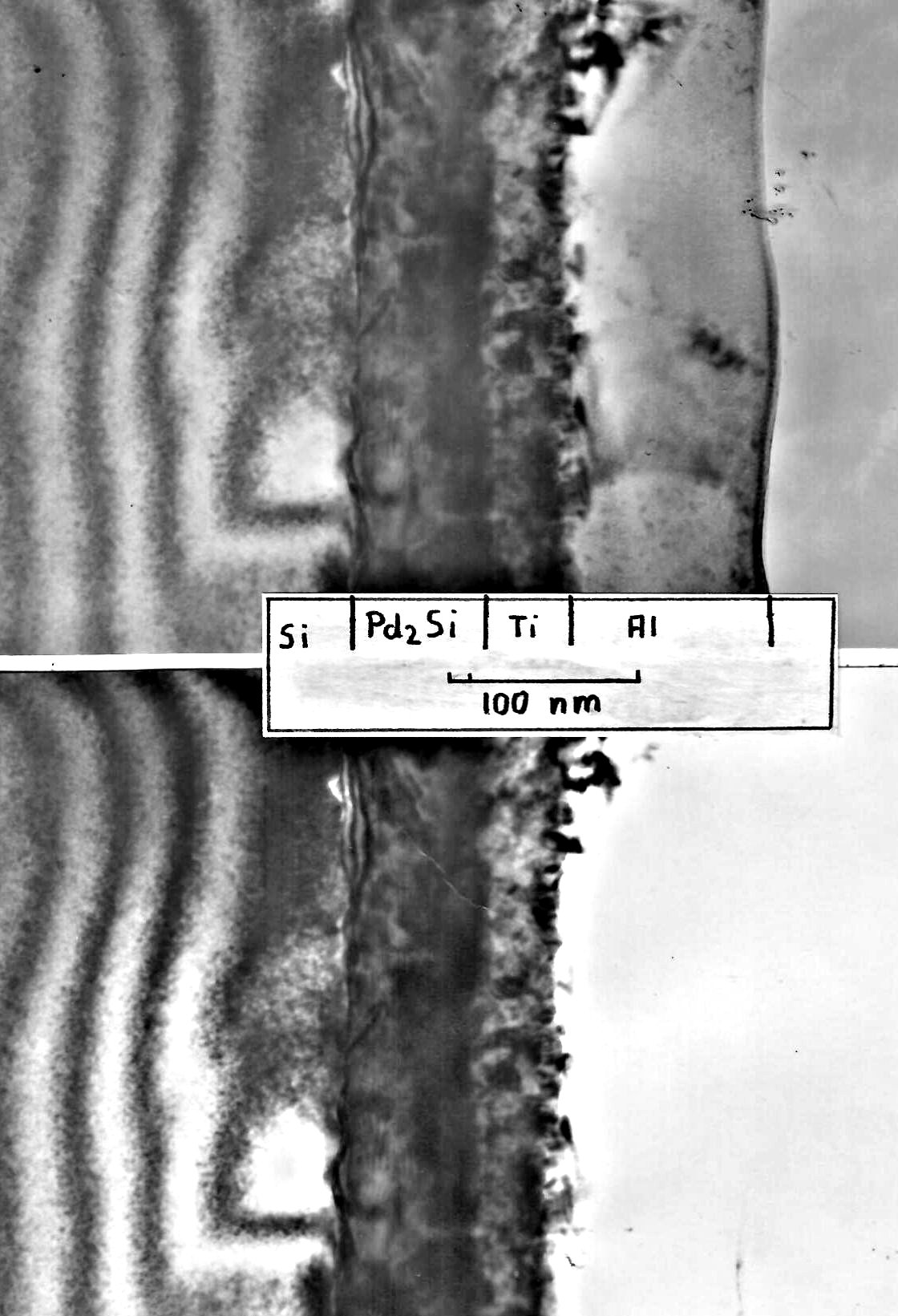

However, as soon as a negative got printed on photographic paper, a lot of information

was unavoidably lost. If you could distinguish some 100 grey levels on the negative, you now had at best some 20 on paper.

In other words, formerly distinguishable grey levels are now lumped together to just one. Here is an example: |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

Information loss from negative to paper.

Same negative, printed on "soft" (top)

and "hard (bottom) photographic paper |

|

| | |

|

|

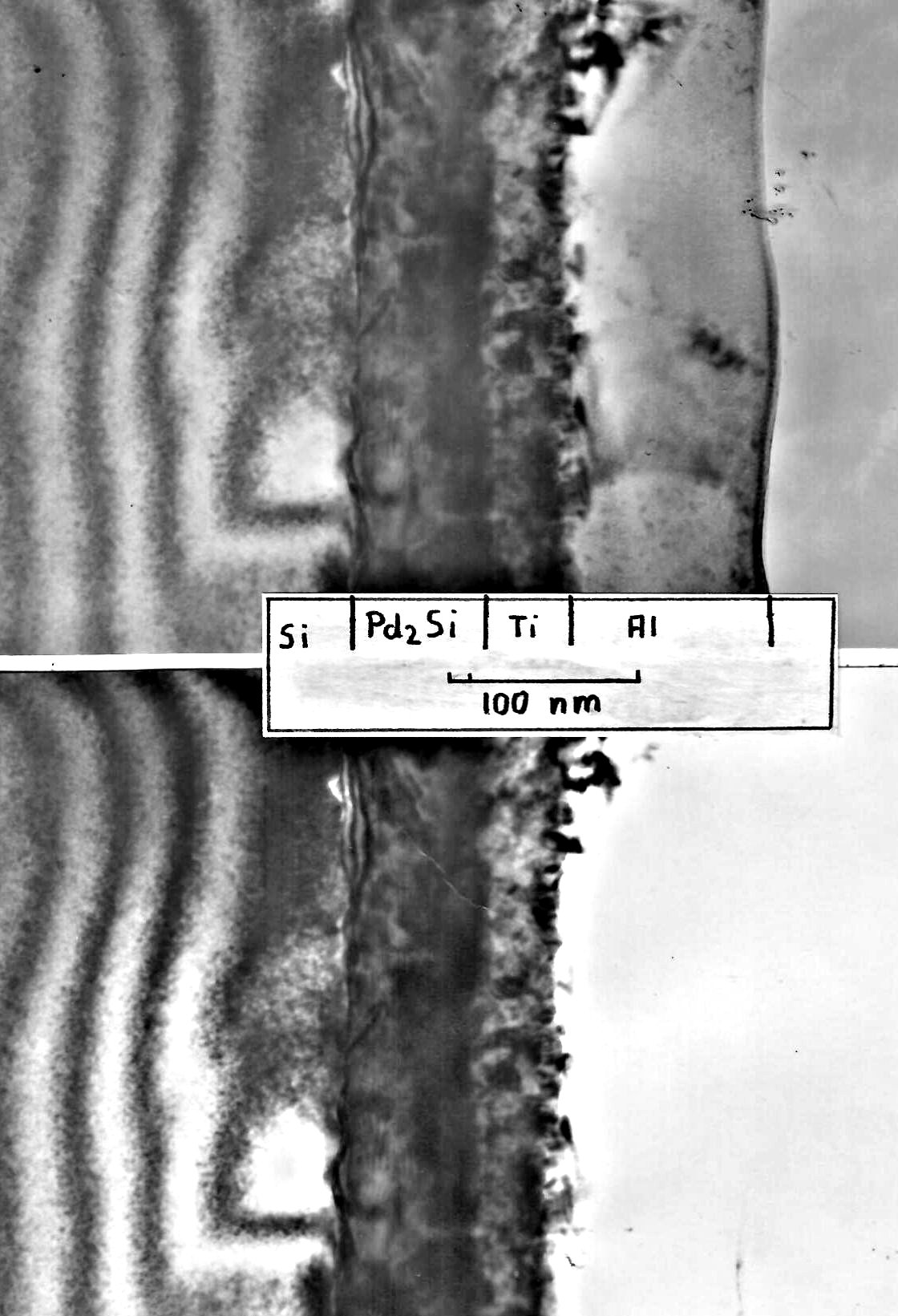

Now you publish your research. No printed journal can accept poster-sized

pictures; you have to cut down the size, often to just credit-card size. Of course, you loose a lot of information this

way. Since journals are not printed on high-quality paper with high-quality printing presses, the picture as it appears

in the journal is once more much worse than the original (small) photo you send in.

However: if you carefully edited

your picture, the reader of the original journal might still be able to see what you want her to see. |

|

|

The journal now sits on a shelf and the paper starts to turn yellow. The ink

starts to fade and the picture "ages", i.e. it looses contrast and thus quality. Eventually somebody copies it,

then somebody else scans that copy and and digitizes it. What you finally see on your computer screen is a tiny fraction

of the information originally contained in the negative. More often the not, what you are supposed to see is no longer there.

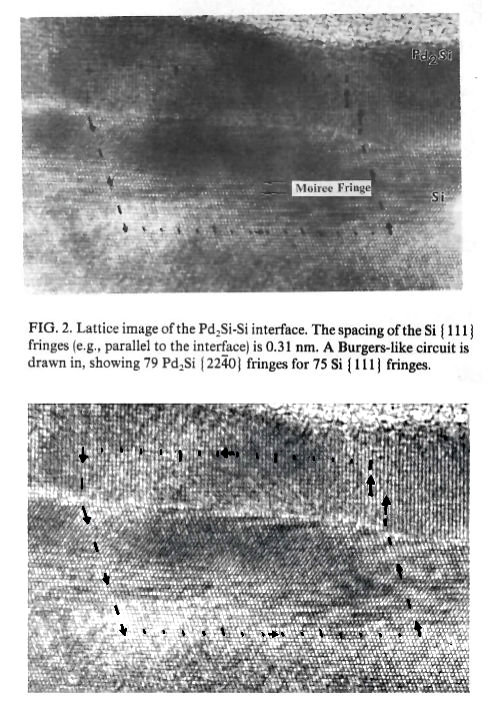

Here is an example |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

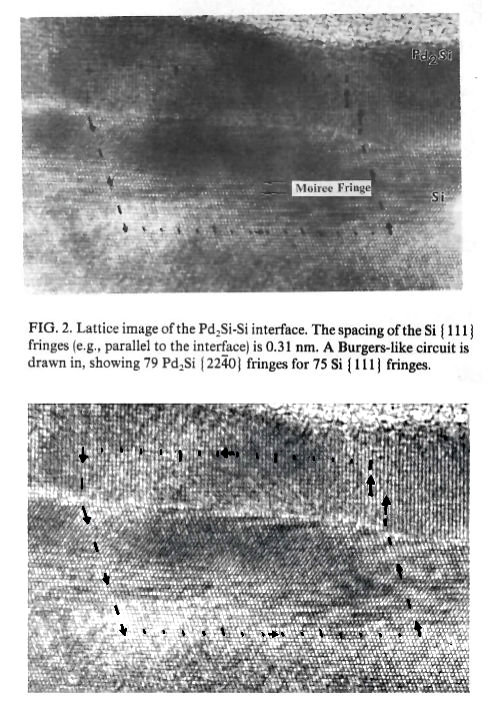

Information loss from paper to journal.

Top: Appearance in original journal; about actual

size.

Bottom: Actual paper print supplied to journal

Here are more pictures from this example |

|

| | |

|

|

That's it. Tough luck. It's all over now, because: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The scientist who produced the original negative, very likely had tossed it out

long ago. Same for large high quality paper prints. Gone.

I know that because it's what I'm just doing. Throwing the

few micrographs I still have into the garbage bin. The negatives I have thrown out long ago,. |

| |

|

Of course, if we do not consider science but literature, most everything that

some minor writer had put on paper will be preserved for eternity in some archive for literature, down to the last little

yellow sticker with the shopping list on it. |

|

In contrast, parts of original science work has gone forever. For

most of these artifacts it will not be a big loss - but then, you never know. Imagine the historians in the distant future

who try to reconstruct how the science / technology explosion in the 20th / 21st century took place in detail. What kind

of artifacts would they like to have? |

| |

|

Actuality, you don't have to look into the future. Try to figure out now how

ancient cultures produced their technological marvels. from the written materials they left and you will be quite frustrated

since there is nothing whatsoever. That is true for the Egyptian pyramids, the Greek “machine

form Antikythera”, most of Roman technology, the forging of an early wootz

sword in India and so on and so forth. |

© H. Föll (Archive H. Föll)