Luristan Swords

IMAS 2

| |

| |

Luristan Swords |

||||

IMAS 2 |

||||

| Note: The “Lurtistn Sword” paged will be formatted somewhat differently (simpler) than the rest. As I grew older, my eyes deteriorated to a point where I can just barely type stuff in my html editor. I apologize for typos and perfectly spelled but wrong words produced by the erroe correction without me noticing. | ||||

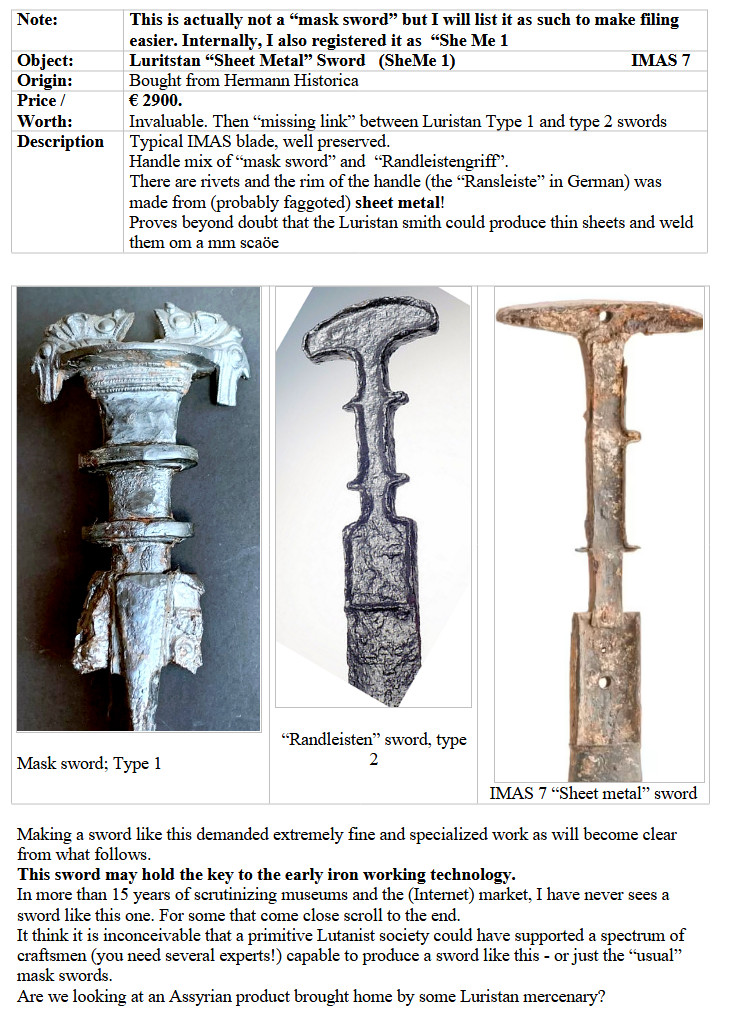

| My internal notes after buying the sword | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Details | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| The “sheet metal” used to make the side bar or “Randleiste” / “Griffleiste” is clearly visible. | ||||||||||

| Some Definitions | ||||||

| The hilt or grip of this sword is a very complex object and I first will introduce

some terms that I am going to use : 1. Blade. This is obvious. 2. Collar / ring. Also obvious 3. Crimp plate - for want of a better term. This structure looks like the crimp plate of “real” IMAS but crimped anything now lost is unclear. It may be part of the tang of the blade, then it might be connected to the tang-less blade below the collar. 4. “Randleiste” or side bar of the crimp plate. Here relatively thick. Either part of the crimpo plate / tang or welded on separately. No traces of welding are visible, however. 5. Lined hole, possible for riveting on the decorative inset but this is questionable. It is lined with a cylinder made from thin metal. 6. Hole not well finished. Possibly intended for riveting on the re-enforcement part see below) but then not needed because that part was too short. 7. Rivet through re-enforcement par and the edge of the crimp plate. 8. Re-enforcement part or strip. Its function is rather unclear. Both strips are too thin to enforce much. Why they are riveted and possibly not welded, is uncles. too. There are 4 rivets altogether. Maybe the main part of the tang below the enforcement strips is majorly flawed at some point, sort of like the “cut" IMAS 8? Then some enforcement would make sense and welding would not be a good option. 9. Protrusions. Somehow fixed to the tang, probably welded. On protrusion is missing; there are no special features at the break-off area. 10. Side bar (“Randleiste”) of very thin metal around the whole upper part of the hilt, some of it missing. Thin, but still with a layered structure as we shall see. 11 Pommel. Likely still part of the tang of the bade and completely surrounded by the sidebar. There is a hole very similar to No 5 that also was lined with a thin cylinder that has mostly disappeared, however. The pommel is heavily encrusted with some mineral. I have refrained from cleaning it so far.

|

| |||||

| First Conclusion | ||||||

| This is a highly complex piece of advanced forging technology There are many questions. Not just the ones alluded to above, but also questions emerging from looking at details. Of coursem the assumption made that this sword coned from Luristan is questionable, too. | ||||||

| The Blade | ||||||

| The blade is corroded but not badly. It is identical in shape to the very typical

Luristan mask sword blades. Elegantly curved with a well -defined midrib. The corrosion pattern is remarkable. Layers of constant thickness are peeling off, starting as bubbles that grow and eventually burst. That indicates that corrosion proceeds through a small opening below a layer in a “weak” interface. It then spreads sideways, mos likely along imperfect welding interfaces. Gas is related and lifts the iron on top to form a bubble. |

| |||||

| The exposed layers seem to run up the ridge to the mid-rip. That indicated that the mid-rip

was not made by welding on cut-out and stacked layers as noted elsewhere in these modules. The layers are rather thin and thus most likely resulted from fagoting the material. Picture on the right taken at some random part of the blade. The rings result from busted bubbles. |

| |||||

| Hilt – Lower Part | ||||||

| It rather appears that the tang of the blade extents all the way to the end of

the hilt. We can’t be sure but I assume that this is the case. The hilt starts with a with a wide kind of collar or ring around the beginning of the tang, right on the lower part of the hilt.

The next part of the hilt, the crimpimg plate in my parlor, was obviously deigned to hold some kind of structure. A sculpture like the animal of a mask sword, wood, ivory, bone, …. whatever. Right in the middle it contains a hole that is still lined by a cylinder of thins iron still sticking up somewhat on both sides. This can be seen in the picture at the right. |

| |||||

| This gives us a first a clear indication that the old smith could work with “sheet metal” in a delicate way. But why lining a hole that we might assume was intended to hold the inlay in place with a rivet? Typically, holes were lined with a metal cylinder if that cylinder extends through the material of inlay ed as shown in the following picture of the hilt of a 19th century kilic. | ||||||

| The questions, of course, are: 1. What use could be served by a lined hole through the whole structure? Not just her but also in the pommel part as we shad see.. 2. How was the lining/inlay held in place if not by a rivet in about the position of the hole? Bending (=crimping) the sidebars of the crimping plate won’t work – they are too small for that. Pondering that, we have to bear in mind that drilling the hole, making a fitting cylinder, and inserting the cylinder securely was not an easy task. The cylinder walls are also somewhat on the thins side for a decorative lined hole, so we just must note this down as unsolved puzzle. Scroll to the end to find a possible answer that occurred to me later There is a second hole, smaller and not fully finished right above the good hole Its purpose is unclear. The lines hole of this kilic had a clear purpose: you could attach some decorative textile with a thin thread. |

| |||||

| The crimping plate has pronounced and relatively thick “Randleisten”

or side bars. How those were made it unclear. I would guess that they were welded on, but there is no indications (like

eroded weld seams) of that. If they were forged in one piece from the tang / blade, we look at the work of a master smith.

If the body of the crimp plate (plus possibly sidebars) are just part of the he tang of the blade is also unclear There are no signs, however, that plates were welded on to the tang or that we have a layered structure. |

||||

| The “crimp plate” part of the sword rather resembles the shape of well-known

bronze daggers form Luristan. O ne is shown on the right. Here is is shown “as cast” but in this case the inlay material was indeed fixed in place by crimping – bending the side bars down. |

| |||

| An example of a (bronze) dagger with a “side bar hilt” filled with some bone. No rivets were used. I guess some kind of glue was employed. |

| |||

| Re-enforcement Strip The re-enforcement strip is fixed with 4 rivets to the tang. One rivet runs through the crimping plate. If the two re-enforcement strips are also fire welded to the tang is unclear. Considering that we look at the result of a lot of intricate fire welding, it is not clear why the old smith felt that rivets were needed, not quite trusting the welding of crimp plate tot the tang The re-enforcement strips extend to the beginning of the pommel, and their function is unclear. They are relatively thin and thus no big enforcement. |

| |||

| “Grip” part of the hilt | ||||||

| The grip part of the hilt consists first of all of the tang plus the two re-enforcement

strips welded / riveted on. The rivet heads are hardly visible. From the tang part two “protrusions” stick out on both side in positions where we would find the rings on a standard IMAS hilt. One protrusion is missing (upper right in the picture). On the tang no indication of the missing protrusion is seen, the area in question just appear to be somewhat more “rusty”. This might indicate that the protrusions were welded on and corrosion penetrated a somewhat flawed interface, removing the protrusion. The protrusions are very thin which is a bit puzzling. It makes it more difficult to run a “Randleistse” / side bar around them and more difficult to fill the space inside with decorative somethings like bone or precious stone. The picture below shows that more clearly.

The protrusion is on the right. It is clearly restricted to the tang and does not extend across the side bars which are are clearly visible. The blueish structure to the left of the protrusion is a remnant of the sheet metal used to make the “Randleiste” / side bar. It can be clearly seen that it consisted of several very thin layers, hinting strongly at faggoted material. |

| |||||

| The Pommel | ||||||

| The general shape of the pommel is what you would get if you cut off part of the disc pommel of a true IMAS. It is not an uncommon shape. The corners are very “narrow”, once again making the fitting of an inset difficult. There is another lined hole, even so the lining cylinder in this case is just barely visible. |

| |||||

| The Side Bar (“Randleiste”) | ||||

| ||||

| The side bar here is shown as it bends around one of the protrusions. The side bar is rather thin - 1.4 mm to be precise. Part of it is broken off at the protrusion and this was probably rather recently since the surface is not yet corroded. | ||||

| ||||

| On this surface but also in other places along the side bar an astonishing feature

is it is clearly visible: The thins side bar is composed of several even thinner layers. In other words: The thin sheet was drawn out from a piece of faggoted iron. If you are unsure about what faggoting means, use the link or check with the Index function of the hyperscript. Bending the side bar strip around the protrusions and the pommel was a difficult thing to do but welding it on seems to be almost impossible. Yet some old smith did just that. Or was he soldering it on? We know from IMAS 4 that soldering was known (at some time at some place and to some smiths). There is no indication of soldering as far as one can see in a microscope, so we must assume that the old smith could do some “micro” fire welding. How he did that without just burning off the fine structure is an enigma to me. We must assume that the “final” side bar went all the way “down” to the crimping plate to hook up with the more solid side bar there. There are no indications of that, however. It would have been a bit awkward, too. Maybe the old smith had a more elegant solution? That would deepens, maybe, on the nature of the “inlay”. |

||||

| The Inlay | ||||

| No traces of the inlay remained, so we can only speculate. The first question

is: One inlay or two – one for the crimping plate, one for the rest? The picture on the right show the “one inlay case” for an old bronze dagger. It features a “real” crimping plate next to the blade and a pommel similar to the one in our case. The inlay material is some bone. My guess is that there were two inlays for our sword. Something elaborate on the crimping plate; e.g. a figure like the animals on real IMAS swords. The rest may have been inlaid with some bone or wood. The smith did not make it easy for the “inlay guy”. The surface onto which the inlay had to be glued or otherwise attaches is rather uneven. The rivet heads are protruding and the re-enforcement strips produce steps on the crimpimg plate and near the pommel. Moreover, fitting the inlay int the protrusions and into the narrow pommel tips, would take very fine carving and fitting of the inlay. Where does this leave us? I will make a few points and then add an epiphany I had months after I had written all of the above: 1. The old smith who forged that sword was a superb craftsman. He worked with very bad iron and had only primitive tools at his disposal but produced a product that modern smith would not easily duplicate. That is also true for the smiths who made the mask swords. 2. I’m convinced that faggoting was used in all the IMAS treated here. That is remarkable, considering that in all of the literature to “old iron”, this technique is never mentioned. 3. The old smith were capable of fire welding (as faggot already proves). But they could do that on very small scales and how they did it is a mystery to me. 4. Luristan shows no traces at all that around 1000 BC a society existed that cold produce “high tech” items like mask swords. But yet, these swords (and bronze objects like the “Master of Animals), have never been found outside Luristan (in contrast the type 2 iron swords). This is a big puzzle. 5. This sword, if properly investigated, may well be the key for the understanding of early iron technology. |

| |||

| The Epiphany (July 20254) | ||||

| Several of the questions raised above find an easy answer if we assume that the

inlay was not done by carving a fitting piece of something precious and riveting it to a very uneven hilt by riveting, but

by simply pouring some molten metal like silve, bronze of gold into the cavity

formed by the hilt and its side bar. Or, maybe, just the liquid “glue” used to fix a precious top layer of

something since two rivets are just nit eniufgh. The “double-disc-pommel” sword listed here as IMAS 15 did show some traces of gold in its hilt and that might well have been cast into the depression still visible there. If that was indeed the case, we now understand: - The holes intended for final decorative rivets or whatever had to be lined and the lining had to stick out to some extent so the liquids metal couldn’t flow out. - The re-enforcement strip is not so much intended for re-enforcement but simply adds volume to the grip and thus decreased the amount of precious metal needed to fill the hilt. - The protrusions and the edge of the pommel could be very small and pointy since the liquid metal would perfectly fill the narrow spaces. No very delicate carving was required. - The big crimp plate might still have held some other precious object. No traces of the inlay are preserved. Maybe the sword was never finished? Otherwise he “Brandpatina” (fire patina) mentioned by the seller would indicate that the sword was exposed to great heat that might have dissolved the inlay metal or at least loosened it. Brandpatina is never found with “true” IMAS’ and thus may indicate that the sword was found in a place a place outside Luristan. | ||||

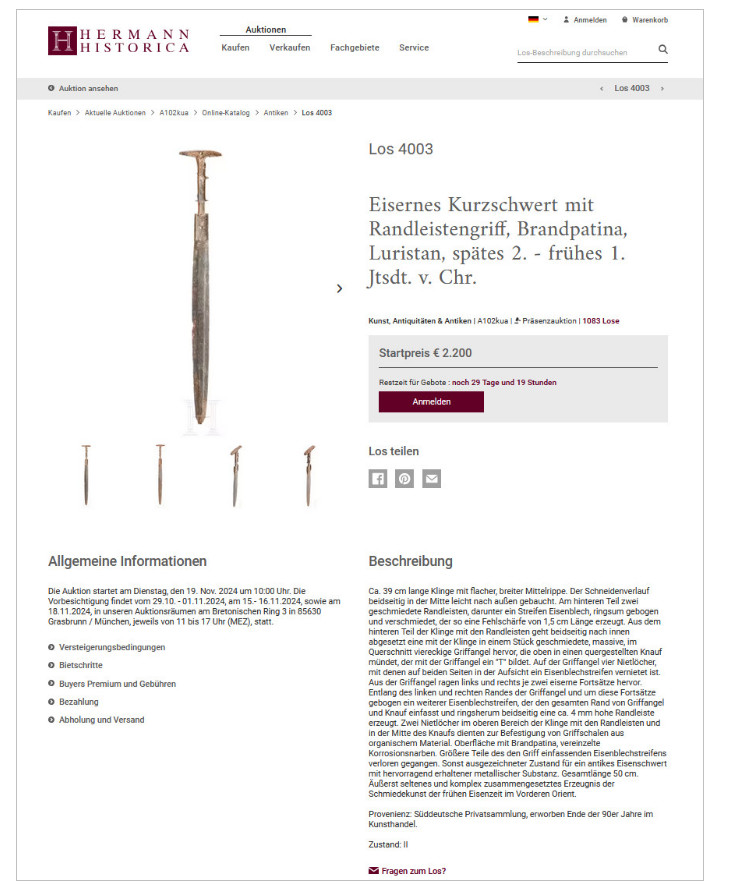

| Results of some literature search for similar swords | ||||

| The IMAS 7 sword is rather unique when it comes to all the details described above.

It is not unique, however, with respect to its general shape. While it is not yet a “proper” Luristan type 2 sword,

similar swords are described in the literature. Not much if anything has been remarkes about the making of these swords

however. Here I restrict myself to the literature cited in the Lurisatn project. | ||||

| K. R. Maxwell-Hyslop et al. In ther 1966 paper show some swords that might be relatives of IMAS 7 here. Since they denounce Lutanist smiths as incompetent, I will not go into details of what they wrote. |

| |||

| E. Schumacher: Eisenschwerter mit Maskenzier aus Luristan Kleemann Festschrift II Teil (=Bonner

Hefte zur Vorgeschichte, n. 4), Bonn, 1973, p-97 ff The papery deals mostly with proper Luri type 1 mask swords but also shows the two sword shewn on the right. This is a very readable paper. It mentions the “elastic band” running around the hilt and daters these swords ito th the 8/9th century BC, supposedly younger then the true IMAS ___________________________________________ Then we have, of course, the “Bible”: Acta Iranica, Vol. XXVI, 2003; and the select articles of Bruno Overlaet listed n the “Project” files. There are not too many swords like the one here but enough top establish the connection to Luristan. We also have a graphic illustrating the development over time: (Below) |

| |||

| The following graphic is rater important for dang Luristan, But don’t let

yourself be let astray. That hardly any objects are shown between 900 and 1050 BC does not mean that there weren’t

any. We just don’t know about that. The sword here may well fit onto this time span since it appears to be less fancy

that the Luristan type II sword shown after 800 BC. There is much more but I rsest my case here. |

||||

| ||||

![]() Master of Animals Finials from Luristan

Master of Animals Finials from Luristan

![]() First Iron Swords - Luristan Type 1 Iron Swords

First Iron Swords - Luristan Type 1 Iron Swords

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)