| |

New Findings |

|

In 2020 I had access to a somewhat unusual Luristan iron mask sword (called type

1 here). That's what it looks like: |

|

|

| | Unusual Luristan type 1 sword |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Heavily corroded and not very remarkable on a first glance.

On a second glance, however, you note that the blade is triangular, not a common feature of Luristan type 1 swords.

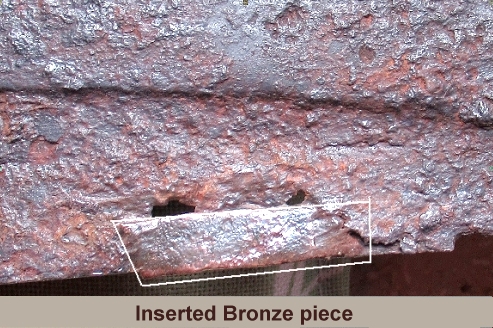

After some cleaning and looking more closely, you realize that two serious damages to the edge of the blade have been repaired

by soldering (with pure tin?) a small piece of bronze into the gap. Here are pictures. |

| |

|

|

|

|

The silvery metal around the bronze pieces (identified by its typical color)

is very soft (easily pierced with a needle) and thus must be tin. |

|

It's a fake, of course. That's what every serious archaeologist would conclude. I'm not so

sure, however. Here are my reasons:

- The sword itself is definitely genuine and not a fake. The only fake then can be the repair, possibly done by a modern

craftsman trying to make the old sword look better.

- When I received the sword, it was covered with grime and rust;: see the topmost picture. The repairs were not visible

and neither were the two big holes in the blade, see below and the small holes next to one bronze insert (whit arrows).

All holes and the bronze inlays only became obvious after cleaning.

|

| |

|

|

Luristan type 1 sword with repairs of the blade (bottom left)

and two big holes |

|

| |

- While it is possible that the forger artificially corroded and dirtied the sword after making the repair, it makes no

sense whatsoever. Why didn't he fill up the holes too? And why making the appearance much worse by corrosion if his goal

was to make the sword look better?

- Now to the killer argument: If the two holes behind the bronze inlay were there originally, the then incomplete repair

makes no sense at all. If they were produced by artificial corrosion after the repair, the whole process makes no sense

at all once more.

|

|

So let's assume that the repair was done when the sword was in use. The holes

visible now are due to corrosion taking place for almost 3000 years.

The questions now is: Would the old Luri smiths

have been capable of doing a repair like this? My answer is: yes! They certainly had noticed that tin has a low melting

point and that you could melt it just by touching it with a medium hot copper rod. Moreover, the molten tin will wet the

copper and coat the surface - provided the copper (or bronze) was clean. The hard part is to get liquid tin to wet iron.

That needs a flux of some kind. While not any fatty substance (like bees wax) will work, some might. We just don't know

those secrets anymore because we buy some working flux somewhere without having the faintest idea of what it contains.

Wikipedia claims that olive oil and Ammonium chloride would work for soldering iron. Ammonium chloride, if you wonder, can

be made from urine. If the old Luristanis had ammonium chloride is doubtful but they may have had similar substances and

who knows what else might work. |

|

|

Why did the use a piece of bronze and not a piece of iron to fill the holes?

Who knows, My guess is that it is just much easier to work with. It it was completely covered with tin, it looks like like

iron and you hardly could see the repaired part of the blade.

My conclusion is |

| |

| |

| |

|

The Luristan smiths could do

complex repairs

The sword shown here is the only

known example

of this antique technique

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

There are probably more examples of repaired blades or other parts of formerly

expensive swords. It's just that nobody noticed so far. First, it might be hard to see below the corrosion layers, and second,

if the repair was good, it is hardly visible. |

| | |

|

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)