10.2.2 Smelting Iron

Then there are the copper smelting modules. Remember this picture? I thought so.

| Smelting Science 1 Furnace and Fire |

How hot?

Economy of size.

Air flow stuff.

Different fuels.

Furnace examples

| Smelting Science 2 Charcoal Technology |

Size counts!

Tree type too.

The dual role of charcoals.

| Smelting Science 3 Smelter Technology |

The real smelter.

Tuyeres and air flow.

There are many important temperatures!

| Smelting Science 4 Air Supply |

Blowpipe limits.

Natural draft and wind.

Only bellows allow good smelting!

| Smelting Science 5 Slag; Tricks |

How hot should it be?

No good slag, no good smelting.

Crucible smelting without CO.

| Smelting Science 6 Serious Iron Smelting |

Baur-Gaessler diagram

Why smelters produce

only wrought iron

Why they don't

| Smelting Light Smelting copper |

The gases in a smelter.

Primitive copper smelting

in salad bowls.

Progress with time

|

There is light a the

end of the tunnel

(and my wife).

Innards of Ephesus amphitheatre

| |

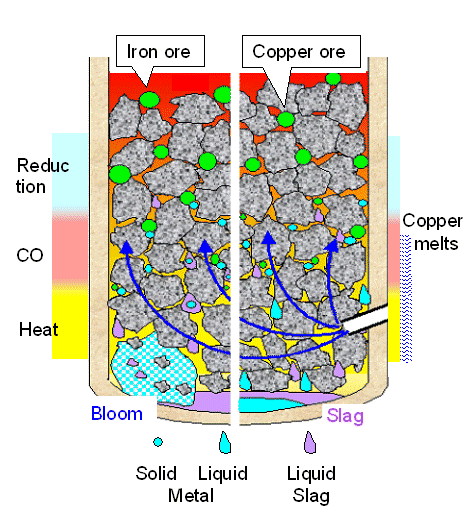

| Comparison of copper and iron smelting |

- We need to produce a lot of heat = energy, and for that we burn = oxidize charcoal at the bottom part in the heat generating zone or oxidizing zone. We need to supply a lot of air through a "tuyere" for this, and it must be just the right amount. Not too much because all the oxygen (O2) in the air supply needs to be used up after a few layers of charcoal, and not too little because we need to get the temperature up quite a bit. The combustion products of the "burning" charcoal layer is hot carbon dioxide (CO2; according to C + O2 Þ CO2 + energy) plus hot nitrogen (N2) from the air.

- The charcoal layer above the burning layer can't burn because there is no more oxygen. If it gets sufficiently heated by the hot gases flowing through, it will produce (hot) carbon monoxide (CO; according to C + CO2 + energy Þ 2CO). This reaction does not produce energy but consumes quite a bit, meaning it cools the gases.

- Ideally, the burning layer should be at least at 1200 oC (2192 oF) and the carbon monoxide producing layer at least at 800 oC (1472 oF) if the smelter is supposed to work efficiently for both copper and iron. That is not all that difficult to achieve - provided you have a decent air supply, always necessitating bellows.

- We now add a certain amount of ore (and maybe "flux") to the charcoal and feed that mix (called "burden") into the smelter from above. The flux is supposed to generate slag, together with all the other stuff in the smelter including "gangue" (the "rock" fragments coming with the ore) and often the clay from the smelter wall material.

- The hot carbon monoxide "reduces" the ore, i.e. turns it into pure metal (abbreviated "M"); most simply according to MO + CO + energy Þ M + CO2. All that chemistry simply states that both metal and carbon monoxide fight for oxygen. The carbon monoxide likes to have more oxygen (turning it into carbon dioxide) and the metal ores like to keep the oxygen it has attached to the metal atoms. The carbon monoxide wins the battle for oxygen against some (not all) metal ores if the temperature is high enough. For copper and iron it always wins. This reduction reaction (= stealing of the oxygen) starts already at rather low temperatures around 400 oC (752 oF) for copper and for some iron ores. The reduction uses up energy and thus cools the smelter. Reducing iron takes substantially more energy than reducing copper and altogether needs somewhat higher temperatures.

- In both cases the ore is turned into the metal with everything being solid all the time. The reduction process fragments the ore pieces into many small and "spongy" metal particles. We now have small metal particles relatively high up in the smelter, mixed with not yet fully reduced ore. The flux materials have also started to react to what we find later in the slag but everything is still solid. At best some glassy very viscous goo is formed.

- As the charcoals at the bottom part get turned into gases, the whole burden moves slowly down - charcoal, ore, metal particles, flux material, slag goo - getting hotter all the time. If that would be all, the metal particles would start to re-oxidize as soon as they move into the oxidation zone and no metal would be produced!

- The slag, after turning liquid, collects in the bottom (as in the picture above). It also might be tapped every once in a while through a tap hole in the "right " position. Accordingly, you produce "production slag", a sort of cylindrical cake found in the bottom pits of furnaces, or tap slag outside the furnace, irregular pieces often with a flow pattern; see below.

| |

| Left: Production slag (about 200 kg, Denmark, 200 AD - 500 AD) Right: Tap slag (unspecified) | |

| Source: Left: Photographed in Copenhagen museum. Left: English Heritage, May 2011; open access Internet |

If we want to produce metal we need to liquefy something above the oxidation zone so it can move down quickly. Either the metal, the slag or - best of all - both! |

- Reducing iron ore generally takes more energy than reducing copper ore. You must therefore increase the ratio of charcoal to ore since you need to burn more charcoal to supply more energy.

- In the almost unavoidable presence of silicates (typical gangue material or the stuff coming with the ore), iron oxide or iron ore is a good flux material. That's why copper smelting was routinely done with iron oxide as flux material. It is then no wonder that iron was produced accidentally every now and then during copper smelting. In fact, as copper smelting techniques progressed, this became a problem.

- Iron smelting thus can be a "self-fluxing" process, meaning you do not have to add flux material as long as the ubiquitous silicates from the gangue were around. Early iron smelters indeed did not use flux materials. Self-fluxing also means that your smelting efficiency goes down, since quite a bit of your ore ends up in the slag as "fayalite", an iron silicate and a major part of slag. With bad luck, slag might have been the only thing you produced in your supposed iron smelting.

- The metallic copper particles are produced in the solid state, just as the iron particles (or any other metal particle in normal smelting). They will melt, however, while still above the hottest part of the smelter, the oxidizing zone where the charcoals burn because there is oxygen. Being liquid, the copper now can trickle down much faster than the whole burden moves down, and thus pass through the very hot oxidizing zone without becoming re-oxidized again. It collects as a liquid at the very bottom, protected by a liquid layer of slag that collects on top of it.

- The metallic iron particles will not

melt. They would move down slowly with the burden and re-oxidize in the hot oxidation zone - if they don't become part of

the liquid slag. Sorry. No liquid slag - no solid iron!

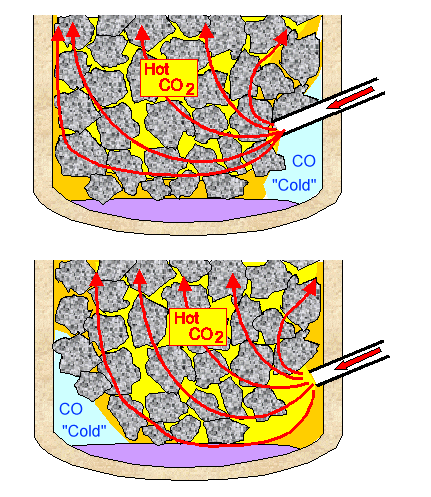

Solid iron is only produced as a bloom if liquid slag envelops the iron particles above the oxidizing zone and sweeps them down quickly to a half-way protected place. There a bloom will grow because iron-particle containing slag is raining down on it, and the iron particles stick together. - However, in a "badly" run smelter, some iron particles produced close to the edge of a smelter may make it down on their own because they might happen to move through "cool" oxygen-deprived places in the oxidation zone. Such a "protected place", with some CO around that's made right there, might be behind the tuyere, in particular if it sticks too far into the smelter and the air flows out too rapidly. Alternatively, it might be on the opposite side of the tuyere, in particular if the air flows out of the tuyere too slowly and doesn't quite make it to the other side. This is schematically illustrated below. Of course, a bit of liquid slag also helps. Mulling this over it becomes clear that the exact geometry of the tuyere (height, angle, diameter, penetration depth into smelter) will be important.

| |

| "Protected zones" where blooms can

grow Top: air velocity too slow Bottom: air velocity too large |

Answer: True enough. It just won't work. The problem is that liquid iron trickling though hot coals and exposed to carbon monoxide at least on parts of its way down will incorporate so much carbon (and whatever else might be around) that you don't get pure liquid iron all the way down but dirty cast-iron! You simply cannot make clean liquid iron in a carbon smelter.

Question: "Excuse me, but why do I get clean liquid copper then?"

Answer: You don't, actually. It just so happens that copper does not incorporate a lot of carbon (look at its phase diagram!). It can and will dissolve a lot of other stuff that happens to be around, however - iron, for example! That is a problem! But when you melt the dirty copper again, getting it ready for alloying and casting, you automatically purify it to some extent.

Question: "Why do we get mostly wrought iron, i.e. rather carbon-free iron in solid iron smelting as I read almost everywhere? After all, the solid particles of rather hot iron could also incorporate some carbon on their way down, even if they hang on to liquid slag! "

Answer: First, in contrast to public opinion and quite involved theory, typical iron smelting throughout the ages did not produce just wrought iron. A bloom with a wild mix of low-carbon wrought iron and all kinds of carbon steel is produced most of the time if you do not run your smelter in an optimized way. However, the iron produced by reduction below about 700 oC (970 oF), has no choice but to be rather pure. If you manage to keep it that way on its way down the smelter, you do end up with wrought iron. But that does not happen "automatically"; you need to know how to achieve that. More details can be found here.

Question: "Why do archeometallurgists, including the ones whose papers I particularly enjoy reading, often mention iron that has been "carburized" if they discuss steel artifacts? Don't they know that you cannot increase the volume carbon concentration of a solid piece of iron by any reasonable treatment? In other words there is no such thing as "carburization"! Then they talk a lot about "primitive small smelters" in the iron age. Don't they know that smelter technology at the beginning of the iron age around 1200 BC was already highly developed?"

Answer: You are right and I don't know the answers. There is indeed a lot of confusion in the general literature about how to make wrought iron, steel and cast iron. As far as the intricacies of smelter technology and the iron-carbon system are concerned - those were and are mysteries to almost all. That's why I'm writing this Hyperscript, after all. Since all and sundry were inclined to believe that bloomeries could only produce wrought iron, you had to assume that some "carburization" was done later if you actually dug up steel.

"Primitive smelters" may simply refer to dug-up facts. Smelters might well have been more primitive for iron than they had been for copper. After the fall of the (Western) Roman empire, bath-room facilities were rather more primitive for about 1500 years than Roman standards, for example, and the same might have happened to metal technology in some places for a while. However, the technology for making the Colossus of Rhodes around 300 BC from bronze and iron / steel was certainly not primitive, to give a counter example.