| | Names around Iron and Steel

|

|

Here is the list of all those more or less weird names

we encountered around iron and steel with an explanation of the origins. |

|

|

- Cementite (German: Zementit). The stoichiometric Fe3C

phase. It is a compound with a complicated lattice and rather hard and brittle.

- Ferrite (German: "Ferrit). The a-phase

with the bcc lattice and very little dissolved carbon.

- Austenite (German "Austenit). The g-phase

with the fcc lattice and some dissolved carbon.

- Pearlite (German: Perlit), the pseudo-phase (correctly a two-phase

mixture; ferrite and cementite, at a certain concentration relation) obtained right below the eutectoid

point at 0.8 % C concentration with the typical "zebra"

appearance.

- Ledeburite (German: Ledeburit); the pseudo-pseudo-phase

(correctly a mixture of cementite with the pseudo-phase pearlite at a certain concentration relation) obtained right below

the eutectic point at 4.3 % C concentration.

- Martensite (German: Martensit); a kind of metastable

version of austenite + carbon; but with a tetragonal lattice and different mechanical

properties (it is very hard and brittle). Martensite is always contained in retained austenite; it cannot exist by itself.

- Bainite (German: Bainit); a mixture of a

- ferrite (to some extent supersaturated with carbon) and cementite, but with a

fine-grained structure quite different from pearlite.

- Graphite (German: Graphit) the ultimate stable hexagonal carbon phase in iron-carbon systems.

|

|

How did those names come into being? Let's see: |

|

The name Cementite - you might have guessed it - has something

to do with the English word "cement", meaning something that binds or glues

things together in this context. |

|

|

In the words of a dictionary. "In 1885, Osmond and Werth

published their "Cell-Theory", in which not only the existence of allotropic forms of iron was proposed (now known

as austenite and ferrite), but in which also a new look at carbide formation was given. Their research on high-carbon steels

showed that the matrix consisted of grains or cells of iron, encapsulated by a thin layer of iron carbide. During solidification,

iron globules, or cells, are formed first and continue to grow. The remaining melt solidifies as iron carbide. In this way,

the carbide-phase actually glues or binds the previous

formed cells together. This view makes it understandable why Osmond called the iron-carbide thus formed, "Ciment" (French for binder or cement)".

Well - we know now that this is

not exactly what happens, but never mind. They did well for

their time. |

|

|

Since English and German have words quite similar to the french ciment,

the French name did not stick but became "cementite" in English and "Zementit" in German. |

|

Ferrite is practically self-explaining: |

|

|

Ferrum is the Latin root for many modern words around

iron and iron compounds. The word ferrum is possibly of Semitic origin. |

|

Austenite was named after Sir William Chandler Roberts-Austen,

a British metallurgist (1843–1902). |

|

|

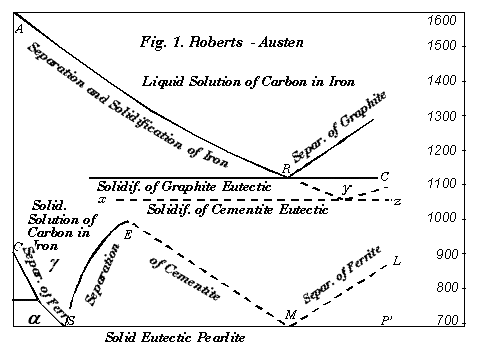

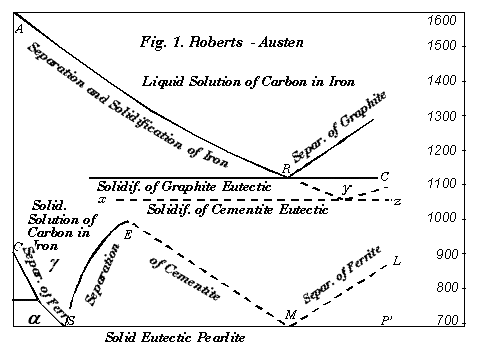

Roberts-Austen published the first iron-carbon phase diagram; in preliminary form 1897 (below),

and in a "final" form in 1899. |

| |

|

| |

|

First phase diagram of iron - carbon by Roberts-Austen

Redrawn as close as possible to the

(rather fuzzy) original with some minor omissions of (unreadable) letters |

|

| | |

|  |

It is obviously not "correct" but it was a major achievement, attacked by his peers. One should

not forget that the ruling dogma stated that no reactions could take place in solids. If you find iron carbide or graphite

in iron, it must have been there in the liquid and just got "frozen-in", for example.

It is also necessary

to point out that those early metallurgists were mainly concerned with cast-iron,

where cementite or graphite could be found. It is hard for us now to imagine what a hopelessly complex task it must have

been to bring some systematic science into to the world of iron, steel and cast-iron. There were countless observations,

measurements and analyses, some wrong, some good - and no way to tell. |

|

Pearlite has its name form the pearl-like luster and iridescence

of its appearance. I have yet to see that for myself or find a picture substantiating that claim. I also could not yet find

out, who coined this name and made it stick. |

|

|

However, quite recent research can provide an explanation why this particular structure is

pearl-like in appearance: The regular spaced lamellae of optically quite different materials form a kind of "photonic crystal" with optical properties quite different from those of

the constituents. About this I know quite a bit; see the link. Real pearls get their luster from the same mechanism; the

name "Pearlite" thus is more fitting than its inventor could have known. |

|

Ledeburite is named after Adolf Ledebur (1837-1916). It is only important for cast-iron. |

|

|

Ledebur was the first Professor for "Eisenhüttenkunde"

(iron smelting lore) at the (famous) Bergakademie Freiberg. In 1882 he discovered the iron-carbon "Mischkristalle"

and became rather famous. "Ledeburite" as a name for the iron - cementite eutectic was adopted in honor of his achievements.

|

|

Martensite was named after Adolf Martens (1850 - 1914). |

|

|

One needs to be careful here: Around 1900, what we call austenite now was called martensite

then! |

|

|

Martens started as an engineer, made it to the director of the royal mechanical laboratory,

which evolved into the "Staatliche Materialprüfungsamt" in Berlin. In Germany, a prestigious prize is now

awarded in his name. |

|

Bainite is named after the American chemist E. C. Bain. In the words of an US

source: |

|

|

"The history of austempering

begins in the 1930's, when Grossman and Bain, working for the United States Steel Laboratories, were evaluating the

metallurgical response of steels cooled rapidly from 1450°F (788C) to intermittently high temperatures and held

for various times. The outcome of their pioneering research is what we now commonly call the "isothermal transformation

diagram" Grossman and Bain were familiar with the conventional metallurgical structures of ferrite, pearlite and martensite.

What they discovered, however, was another structure, formed above the martensite start temperature (Ms) and below the pearlite

formation region. In steels, this structure took the form of an acicular (plate-like) structure with a feathery appearance.

X-ray diffraction later identified this structure as a combination of ferrite and metal carbide. The resultant structure,

termed "Bainite" was found to be stronger and tougher than a comparable "quenched

and tempered" structure. |

| |

|

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)