|

The relative permeability

µr of a material "somehow" describes the interaction of magnetic (i.e. more or less all)

materials and magnetic fields H, e.g. vial the equations Þ |

|

|

|

|

B is the magnetic flux density or magnetic induction,

sort of replacing H in the Maxwell equations whenever materials are encountered. |

|

|

|

L is the inductivity of a linear solenoid, or )coil or inductor) with length

l, cross-sectional area A, and number of turns t, that is "filled" with

a magnetic material with µr. | |

|

|

n is still the index of refraction; a quantity

that "somehow" describes how electromagnetic fields with extremely high frequency interact with matter.

For

all practical purposes, however, µr = 1 for optical frequencies |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Magnetic fields inside magnetic materials polarize the material, meaning that

the vector sum of magnetic dipoles inside the material is no longer zero. |

| |

|

|

The decisive quantities are the magnetic dipole moment

m, a vector, and the magnetic Polarization J, a vector,

too. | |

|

|

|

Note: In contrast to dielectrics, we define an additional quantity, the magnetization

M by simply including dividing J by µo. |

|

|

|

The magnetic dipoles to be polarized are either already present in the material (e.g. in Fe,

Ni or Co, or more generally, in all paramagnetic materials, or are induced by the magnetic fields (e.g. in diamagnetic

materials). | |

|

|

The dimension of the magnetization M is [A/m]; i.e. the same as that of the magnetic field.

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

The magnetic polarization J or the magnetization M

are not given by some magnetic surface charge, because Þ. |

|

| There is no such thing as a magnetic monopole,

the (conceivable) counterpart of a negative or positive electric charge |

|

| | |

| |

|

|

The equivalent of "Ohm's law", linking current density to field strength

in conductors is the magnetic Polarization law: |

|

| M | = |

(µr - 1) · H | | | |

| | M | := |

cmag · H |

|

|

|

|

The decisive material parameter is cmag = (µr –

1) = magnetic susceptibility. |

|

|

|

The "classical" induction B and the magnetization are linked as shown.

In essence, M only considers what happens in the material, while B looks at the total

effect: material plus the field that induces the polarization. | |

| | |

| |

|

Magnetic polarization mechanisms are formally similar to dielectric polarization

mechanisms, but the physics can be entirely different. | |

| Atomic mechanisms of magnetization are not directly analogous to the

dielectric case |

|

|

Magnetic moments originate from: |

| |

|

|

The intrinsic magnetic dipole moments m of elementary particles with spin is

measured in units of the Bohr magnetonmBohr. | |

| mBohr = |

h · e

4p · m*e |

= 9.27 · 10–24 Am2 |

| me = |

2 · h · e · s

4p · m*e |

= 2 · s · m Bohr |

= ± mBohr |

|

|

| |

|

The magentic moment me of the electron is Þ

| |

|

|

Electrons "orbiting" in an atom can be described as a current running in a circle

thus causing a magnetic dipole moment; too | |

| | |

| |

|

The total magentic moment of an atom in a crystal (or just solid) is a (tricky

to obtain) sum of all contributions from the electrons, and their orbits (including bonding orbitals etc.), it is either: |

| |

|

|

Zero - we then have a diamagmetic material. |

|

Magnetic field induces dipoles, somewhat analogous to elctronic polarization in

dielectrics.

Always very weak effect (except for superconductors)

Unimportant for technical purposes |

|

|

|

In the order of a few Bohr magnetons - we have a essentially a paramagnetic material. |

|

Magnetic field induces some order to dipoles; strictly analogous to "orientation

polarization" of dielectrics.

Always very weak effect

Unimportant for technical purposes |

|

| |

| |

|

|

In some ferromagnetic materials spontaneous ordering of magenetic

moments occurs below the Curie (or Neél) temperature. The important familiess are |

| |

|

|

- Ferromagnetic materials ÝÝÝÝÝÝÝ

large µr, extremely important.

- Ferrimagnetic materials ÝßÝßÝßÝ

still large µr, very important.

- Antiferromagnetic materials ÝßÝßÝßÝ

µr » 1, unimportant |

|

Ferromagnetic materials:

Fe, Ni, Co, their alloys

"AlNiCo", Co5Sm,

Co17Sm2, "NdFeB" |

|

| | |

| |

|

|

There is characteristic temperatuer dependence of µr for

all cases | | |

| | |

| |

|

Dia- and Paramagentic propertis of materials are of no consequence whatsoever

for products of electrical engineering (or anything else!) | |

Normal diamagnetic materials: cdia

» – (10–5 - 10–7)

Superconductors (= ideal diamagnets): cSC = – 1

Paramagnetic

materials: cpara

» +10–3 |

|

|

|

Only their common denominator of being essentially "non-magnetic" is

of interest (for a submarine, e.g., you want a non-magnetic steel) | |

|

|

For research tools, however, these forms of magnitc behavious can be highly interesting ("paramagentic

resonance") | |

| |

| |

|

|

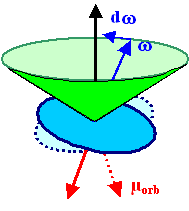

Diamagnetism can be understood in a semiclassical (Bohr) model of the atoms as

the response of the current ascribed to "circling" electrons to a changing magnetic field via classical induction

(µ dH/dt). | |

|

|

|

The net effect is a precession of the circling electron, i.e. the normal vector of its orbit

plane circles around on the green cone. Þ |

|

|

|

The "Lenz rule" ascertains that inductive effects oppose their source; diamagnetism

thus weakens the magnetic field, cdia < 0 must apply. |

|

|

| | |

|

|

Running through the equations gives a result that predicts a very small effect.

Þ

A proper quantum mechanical treatment does not change this very much. |

|

| cdia = –

|

e2 · z · <r>

2

6 m*e |

· ratom |

» – (10–5 - 10–7) |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

The formal treatment of paramagnetic materuials is mathematically completely identical

to the case of orientation polarization | |

| W(j) = – µ0 · m

· H = – µ0 · m · H · cos j |

| | Energy of magetic dipole in magnetic field |

| N[W(j)] = c · exp –(W/kT)

= c · exp | |

m · µ0 · H · cos j

kT |

= N(j) |

| | (Boltzmann) Distribution of dipoles on energy states |

| M | = |

N · m · L(b) |

| | | | | | |

| | | b |

= | µ0 · m · H

kT | | | |

|

| Resulitn Magnetization with Langevin function L(b) and argument b |

|

|

|

The range of realistc b values (given by largest H

technically possible) is even smaller than in the case of orientation polarization. This allows tp approximate L(b) by b/3; we obtain: |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

Insertig numbers we find that cpara is indeed

a number just slightly larger than 0. | |

| | |

| |

|

|

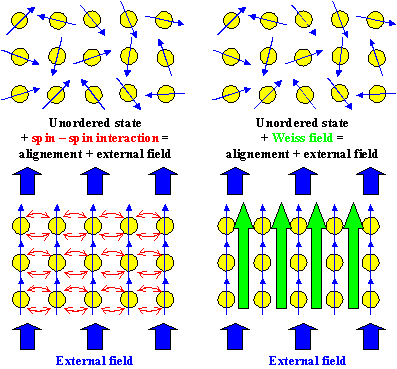

In ferromagnetic materials the magnetic moments of the atoms are "correlated"

or lined-up, i.e. they are all pointing in the same direction | |

|

|

|

The physical reason for this is a quantum-mechanical spin-spin interaction that

has no simple classical analogue. | |

|

|

However, exactly the same result - complete line-up - could be obtained, if the magnetic moments

would feel a strong magnetic field. | |

|

|

In the "mean field" approach or the "Weiss" approach to ferromagnetism,

we simply assume such a magnetic field HWeiss to be the cause for the line-up of the magnetic moments.

This allows to treat ferromagnetism as a "special" case of paramagnetism, or more generally, "orientation

polarization". | |

| | |

| |

|

For the magnetization we obtain Þ |

|

| J | = |

N · m · µ0 · L(b) |

= |

N · m · µ0 · L |

æ

è |

m · µ0 · (H + w · J)

kT | ö

ø

|

|

|

|

|

The term w · J describes the Weiss field via Hloc

= Hext + w · J; the Weiss factor w is the decisive (and unknown)

parameter of this approach. | |

|

|

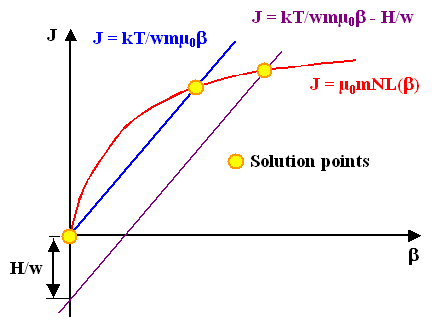

Unfortunately the resulting equation for J, the quantity we are after, cannot

be analytically solved, i.e. written down in a closed way. | |

| | |

| |

|

Graphical solutions are easy, however Þ |

|

|

|

|

From this, and with the usual approximation for the Langevin function for small arguments,

we get all the major ferromagnetic properties, e.g. - Saturation field strength.

- Curie temperature TC.

| TC | = |

N · m

2 · µ02 · w

3k |

|

- Paramagnetic behavior above the Curie temperature.

- Strength of spin-spin interaction via determining w from TC.

| |

|

|

As it turns out, the Weiss field would have to be far stronger than what is technically achievable

- in other words, the spin-spin interaction can be exceedingly strong! | |

| | |

| |

|

In single crystals it must be expected that the alignments of the magnetic moments

of the atom has some preferred crystallographic direction, the "easy" direction. |

|

Easy directions:

Fe (bcc) <100>

Ni (fcc) <111>

Co (hcp) <001> (c-direction) |

|

| | |

| |

|

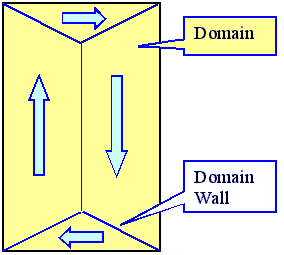

A single crystal of a ferromagnetic material with all magnetic moments aligned

in its easy direction would carry a high energy because: | |

|

|

|

It would have a large external magnetic field, carrying field energy. |

|

|

In order to reduce this field energy (and other energy terms not important here),

magnetic domains are formed Þ. But the energy gained has to be "payed for"

by: | |

|

|

Energy of the domain walls = planar "defects" in the magnetization structure. It

follows: Many small domains —> optimal field reduction —> large domain wall energy "price". |

|

|

|

In polycrystals the easy direction changes from grain to grain, the domain structure has to

account for this. | |

|

|

In all ferromagnetic materials the effect of magnetostriction (elastic deformation tied to

direction of magnetization) induces elastic energy, which has to be minimized by producing a optimal domain structure. |

|

|

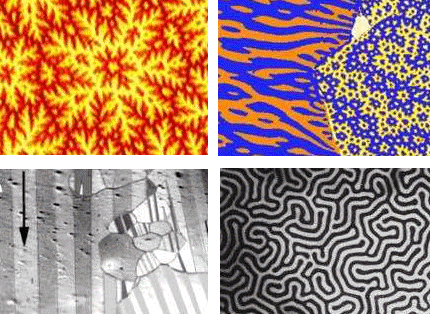

The domain structures observed thus follows simple principles but can be fantastically

complicated in reality Þ. | |

| |

| |

|

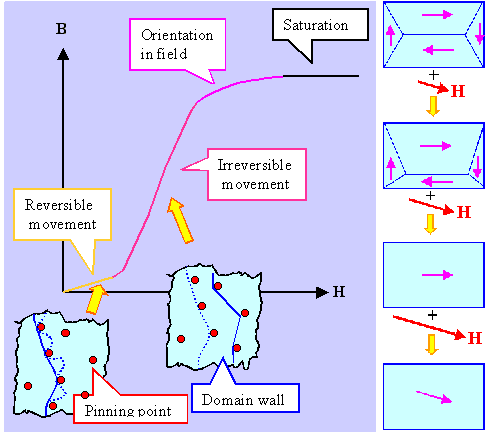

For ferromagnetic materials in an external magnetic field, energy can be gained

by increasing the total volume of domains with magnetization as parallel as possible to the external field - at the expense

of unfavorably oriented domains. | |

|

|

|

Domain walls must move for this, but domain wall movement is hindered by defects because of

the elastic interaction of magnetostriction with the strain field of defects. |

|

|

|

Magnetization curves and hystereses curves result Þ,

the shape of which can be tailored by "defect engineering". |

|

|

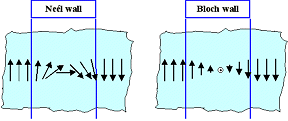

Domain walls (mostly) come in two varieties:

- Bloch walls, usually found in bulk materials.

- Neél walls, usually found in thin films.

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

| |

|

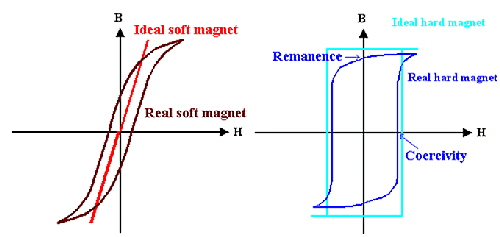

Depending on the shape of the hystereses curve (and described by the values of

the remanence MR and the coercivity HC, we distinguish hard and soft magnets

Þ. | |

|

|

Tailoring the properties of the hystereses curve is important because magnetic

losses and the frequency behavior is also tied to the hystereses and the mechanisms behind it. |

|

|

|

Magnetic losses contain the (trivial) eddy current losses (proportional to the conductivity

and the square of the frequency) and the (not-so-trivial) losses proportional to the area contained in the hystereses loop

times the frequency. | |

|

|

The latter loss mechanism simply occurs because it needs work to move domain walls. |

|

|

It also needs time to move domain walls, the frequency response of ferromagnetic

materials is therefore always rather bad - most materials will not respond anymore at frequencies far below GHz. |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Uses of ferromagnetic materials may be sorted according to: |

| |

|

|

Soft magnets; e.g. Fe - alloys |

|

- Everything profiting from an "iron core": Transformers, Motors, Inductances, ...

- Shielding magnetic fields.

|

|

|

|

Hard magnets; e.g. metal oxides or "strange" compounds. |

|

- Permanent magnets for loudspeakers, sensors, ...

- Data storage (Magnetic tape, Magnetic disc drives, ...

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

Even so we have essentially only Fe, Ni and Co (+ Cr,

O and Mn in compounds) to work with, innumerable magnetic materials with optimized properties have been developed. |

|

Strongest permanent magnets:

Sm2Co17

Nd2Fe14B |

|

|

|

New complex materials (including "nano"materials) are needed and developed all the

time. | |

|

| | |

|

|

Data storage provides a large impetus to magnetic material development and to employing

new effects like "GMR"; giant magneto resistance; a purely quantum mechanical effect. |

| |

| | |

|

© H. Föll (Electronic Materials - Script)