|

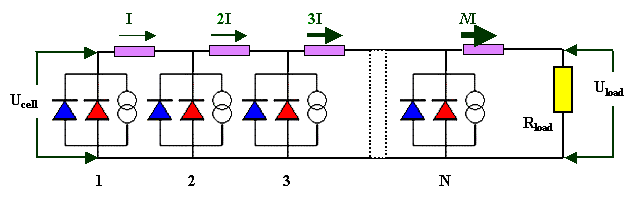

We take a number N of solar cells; assuminng that all oft them are

perfectly identical, to keep things simple at first. We also assume that there are no shunts in those solar cells, but that

they have some series resistance RSE. |

|

|

The first basic question now is : How can you deliver maximum power into some

load resistor Rload - by switching the N solar cells in series or parallel? |

|

Let's look at switching in parallel first. |

| |

|

|

|

Every individual solar cell delivers a current I, theses currents

add up, and the current flowing through the load resistor Rload of the solar cell No. k

under short circuit conditions is Iload(k) = k ·I |

|

|

The corresponding total voltage drop in all N series resistor each

with resistivity RSE is USE given by |

| |

| USE | = |

I · (RSE + 2RSE + 3RSE

+ .... + NRSE) | | | |

| | |

= |

I · RSE · ½N · N |

(remember young Gauss?) |

| | | |

| | = |

I · RSE ·N2

2 | |

|

|

|

The product of maximum output voltage times current give some fictive power Pparallel

akin to just multiplying ISC and UOC of the "ideal" solar cell.

The actual power Pload, pdeposited into the load resistor depends, of course, on the value Rload;

it will be maximal for some specific value of Rload but always smaller than Pparallel. |

| |

| Pparallel | = |

N · I · (Ucell – ½ N2

· I · RSE) | | |

| |

| | = |

N · I · Ucell – ½N3

· I2 · RSE |

|

|

|

The total losses due to series resistors thus are at least Ploss,

p = ½N3 · I2 · RSE |

| | |

|

| |

|

Now let's look at a series connection. |

|

|

|

|

The current flowing through the load resistor is I |

|

|

|

The voltage Uload is N times the cell

voltage minus the voltage drop in the internal resistance, i.e. minus N · RSE · I;

we have Uload = N · (Ucell – I · RSe) |

|

|

|

The power Pseries deposited in the load resistor is

such | |

|

| |

|

| |

| Pseries | = |

I · N (Ucell – I · RSE) |

| | | | | |

= |

I · N · Ucell – I2 ·

N · RSE |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

Your total losses due to series resistors thus are Ploss,

s = N · I2 · RSE |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The relation between the losses of a solar cell array in in parallel or in series thus are |

| |

|

|

Ploss, p

Ploss, s

| = |

N3 · I2 · RSE

2 ·

N · I2 · RSE | = |

N2

2 |

|

|

| | |

|  |

In words: You must switch your solar cells in series! You

loose far too much power if you have them in parallel |

| |

|

|

We take a number N of solar cells; assuminng that all oft them except for one are perfectly identical, to keep things not too simple anymore. |

|

|

We consider two extrem cases for both variants, series and parallel connection

of N – 1 identical good cells and one bad one:

- The bad cell has a very large series resistance and no noticeable shunt resistance

- The bad cell has a regular series resistance and a very small shunt resistance.

|

|

Let's see what will happen in the parallel world. All we have to do is to image

that the series reistor of cell No. N is very large, or that the whole cell is just a small resistor in parallel

to the load. What will happen? |

|

|

In the first case you simply loose most of

your voltage at the high series resistance of the defective cell. The power output will go down dramatically, or simply

proportionally to the added series resistance. It will also matter which one of the N cells is the defective

one. |

|

|

In the second case you just add another parasitic

load resistor to the intended load, funneling off some of the current. Again, the power output will go down dramatically,

proportional to 1/RSH. |

|

Let's see what will happen in the serial world. |

|

|

In the first case you simply loose most of

your voltage at the high series resistance of the defective cell, and it doesn't matter which cell it is. You can consider

the surplus resistance as a parasitic addition to the load resistor. The power output will go down dramatically, again proportionally

to the added series resistance. |

|

|

In the second case you just loose the power

not generated by the defective cell. The current of all the other cell passes through the (small) shunt resistance without

much of a voltage drop. |

|

Again, we have compelling reasons to go with series connections. We also see that

we must watch out for high series resistance - it does more damage on the whole than the occasional shunt. |

|

The most important insight, however, is that one bad cell in an array of, let's

say 100 cells, may bring down the total efficieny of the module - that's essentially what we are discussing - quite

disproportionally, i.e. not by just 1 %, but by far more. |

| | |

|

© H. Föll (Semiconductor Technology - Script)

![]() 8.1.2 Solar Cell Current-Voltage Characteristics and Equivalent Circuit Diagram

8.1.2 Solar Cell Current-Voltage Characteristics and Equivalent Circuit Diagram