|

The potential for the electron in a crystal lattice is periodic with the lattice, i.e. V(r

+ T) = V(r) with T = translation vector of the lattice. It is therefore always possible

to develop V(r) into a Fourier series

in reciprocal space and we obtain |

| |

| V( r) | = |

SG

VG · exp (i · G ·r) |

|

|

|

|

The VG are the Fourier coefficients of the potential. |

|  |

G

is a reciprocal lattice vector; the sum must be taken over all reciprocal vectors and there are infinitely many.

We will, however, no longer use the underlining for vectors. |

|

|

In simple approximations it will be generally sufficient to consider only a few vectors of reciprocal space;

i.e., most VG are 0. |

|

The wave function y(r) can also be Fourier transformed.

Without loss of generality it can be expressed as a sum of the plane waves which are the solutions of the free electron

gas problem (with V = 0): |

| |

| y(r) | = |

S k

Ck · exp (ikr) |

|

|

|

The Ck

are the Fourier coefficients of the wave function and k denotes the wave vector as obtained from the

simple free electron gas model (e.g. kx = ± nx

· 2p/ Lx). |

|

|

Since L

x must be a multiple of the lattice constant a, i.e. Lx = N ·

a (with N = Lx/a = number of elementary cells in L x),

all k-vectors can be written as |

| |

|

|

|

We know that 2p/ a is simply the magnitude of the reciprocal lattice

vector characterizing the set of planes perpenduclar to the direction of a (if taken as a unit vector of the

elementary cell) with spacing a; i.e. for the {100} planes, nx · 2p/a

gives the whole set of reciprocal lattice vectors with the same direction, and 1/N intersperses N

points between the reciprocal lattice points defined by n x. |

|  |

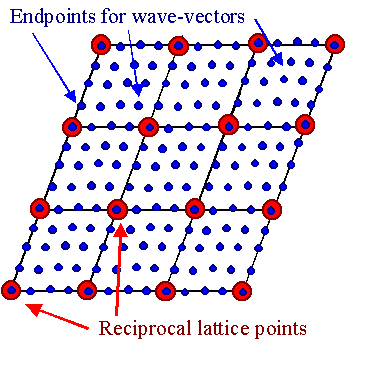

In other words and generalized for three dimensions: The allowed points for k-vectors are

points in reciprocal space interspersed between the lattice points of the reciprocal lattice. |

|

We have the following picture, with (for reasons of clarity, very few) blue

k-points between the red G-points: |

| |

|

|

|

The picture makes clear that any arbitrary wave vector k can be written

as a sum of some reciprocal lattice vector G plus a suitable wave vector k'; i.e., we can always

write k = G + k'

and k' can always be confined to the 1. Brillouin zone (= the elementary

cell of the reciprocal lattice). |

|

|

Alternatively, any reciprocal lattice vector G can always be written as G = k

– k' This is a relation that should look familiar;

we are going to use it a few lines further down. |

|

If we now pluck both expressions into the Schrödinger

equation |

| |

| – |

2 2

2m |

· Dy |

+ V(r) · y(r) |

= |

E · y(r) |

|

|

|

|

and do the differentiations, we obtain |

| |

| Sk |

( · k)2 · k)2

2m |

· Ck · exp (ikr) + Sk'

SG Ck' · VG · exp (i

· [k' + G] · r) | = |

E · Sk Ck · exp (ik r)

|

|

|

|

|

We have written k' in the double sum to indicate that it is not important

how we sum up the components. That allows us to rename the summation indices and to replace k' as shown:

|

| |

|

|

|

Reshuffling the equation we obtain |

| |

| S k exp (ik · r)

| · |

æ

ç

è |

æ

è |

( · k)2 · k)2

2m |

– E | ö

ø

|

· Ck + SG (Ck –

G · VG) |

ö

÷

ø |

= 0 |

|

|

|

|

If this looks a bit like magic, you should consult the link. |

|

Since this equation holds for any space vector r, the expression in the red brackets

must be zero by itself and we obtain |

| |

æ

è |

(  · k)2 · k)2

2m |

– E | ö

ø

|

· Ck + SG(Ck

– G · VG) | = |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

This is nothing but Schrödinger's equation for crystals written as a collection of algebraic

equations. It couples the Fourier coefficients VG of a periodic potential (which we know) to the

Fourier coefficients Ck and Ck – G of the wave functions (which

we want to calculate) in an unique way. |

|

|

If you have trouble visualizing this, write some parts of this infinite system of equations in a matrix

as shown in the link for a slightly different situation. |

|

The problem now is much simplified. While our original Fourier expansion of the wave function

was a sum containing a large number of coefficients Ck because we have a large number of k's,

we now only have to consider a sum over G's - of which we have far less (if still infinitely many). |

|

|

This is so because our system of equations from above only contains Ck – G.

Solving it, gives a definite wavefunction for any chosen k as a sum over just Ck – G

coefficients. |

|

|

Since we can express all k vectors outside the 1st Brillouin zone as a sum of a k-vector

in the first Brillouin zone and some G-vector (see above), we only have to

consider N terms for the k-values. |

|

|

Since we have N

k-vectors, we have N sets of equations, each one describing one wavefunction yk

of which we now know that it can be expressed as a Fourier series over points in reciprocal space positioned at

k – G with G = any reciprocal wave vector. This means we have |

| |

| yk(r) | =

| SG

Ck – G · exp(i · [k – G] ·r) |

|

|

|

|

or, after rewriting the exponential |

| |

| yk(r) | =

|

SG Ck – G ·

exp (–iGr) · exp (ikr) |

|

|

|

The first term shown in red, upon inspection, is nothing

but the Fourier series of some function uk(r) that has the periodicity of the lattice; it is defined by:

|

| |

| uk(r) | = |

SG

Ck – G · exp (–iGr) |

|

|

|

|

We thus obtain |

| |

| yk(r) | =

| uk(r) · exp (–iGr) |

= | SG

Ck – G · exp (–iG r) · exp (ik r) |

|

|

|

And this is Bloch's theorem that we endeavored to prove. |

| | |

© H. Föll (Semiconductors - Script)

![]() Double Sums and Index Shuffling

Double Sums and Index Shuffling