| |

|

|

Calculating a critical phenomena, a situation where something changes abruptly

to something else, is usually not so easy. How many straws can a camel bear before one more breaks its back? 1). So be happy that it is relatively easy to get a grasp for buckling. That is to a large extent

due to the fact that buckling of material under compressive stress is an extremely important phenomenon for all builders.

If the wall of your castle or the columns holding the roof of your cathedral start to buckle, it's all over. Major minds

worked on the problem and it was no less a guy than Leonhard Euler

(1707 – 1783) who derived the correct formula for the critical force or better critical stress. Since then other great

brains have derived simpler ways to tackle the problem, and here I will use Richard

Feynman's way. |

|

|

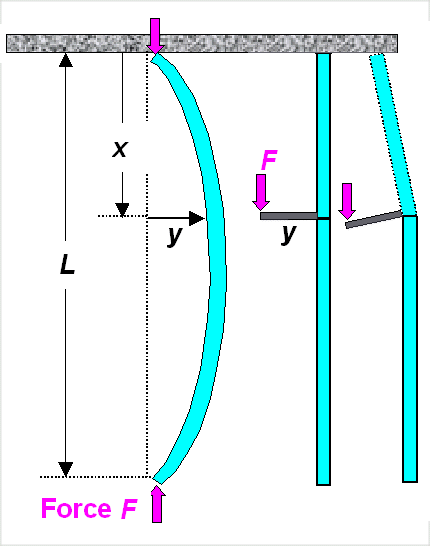

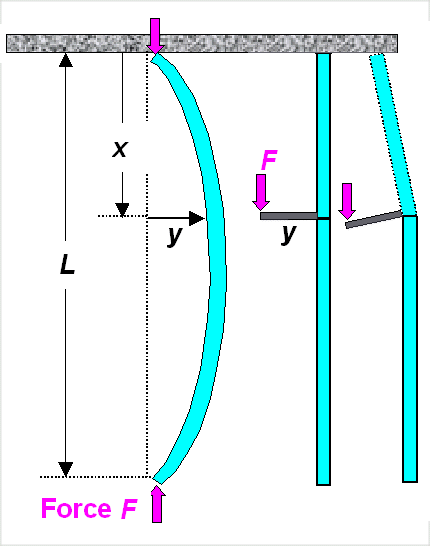

We look a the situation where the beam has actually buckled. We can describe

that as shown below: |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| Buckled beam with forces acting on it and why bending torque is F · y

|

|

| | |

|

|

|

We need a force F acting on both ends with reversed signs as shown. This force

induces a momentum or torque T(x) = F · y if you "walk" along the buckled beam

in x-direction. The drawing tries to make clear why.

Using our "master" equation" for beam bending, we get |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

| | |

|

|

|

We have r, the radius of curvatures; Y, Young's modulus, and lA,

the area moment of inertia as the crucial quantities.

As always, for small deflections

y we can approximate the radius of curvature by 1 / r = - d2y / dx2, yielding

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

|

Hello? This is a simple differential equation for y (x) with

the obvious solution |

| | |

|

|

|

| y(x) | = const. · sin |

p · x

L |

|

|

| | |

|

| |

|

We could easily derive the const. but we don't need to do that. What we

do instead is to take the second derivative of the solution and compare it to the equation right above, i.e. |

| | |

|

| |

|

d2y

dx2 |

= – | p2

L2 | · const. · sin |

p · x

L | = |

p2

L2 | y(x) |

|

|

| | |

|

|

Comparing this to the equation two steps above and rewriting

it for the force F, we obtain the final and rather interesting result: |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

| | |

|

|

This is an interesting result because it appeared almost by magic. Well, I told

you that Feynman is tricky. It is really interesting, however, because the Force F is a simple number,

independent of the variables y of the problem. The force just depends of the geometry (L, lA)

and the material (Y) of the beam. That's funny because in the real world you can apply all kinds of forces, smaller

and larger than the force F calculated above. What does that mean? |

|

|

The unavoidable conclusion is that we actually calculated the critical force

Fcrit. For applied forces smaller than Fcrit, all of the above does not

apply, i.e. there is no deflection y and thus no buckling, For forces just equal or somewhat larger than the

critical force, we have buckling with the (by definition small) deflection y. If we increase the force well

beyond the critical force, our approximation for the radius of curvature breaks down, and we have to use the full equation for r.

That is not all that difficult but rather

tedious and we won't go into that. |

|

| |

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)