|

Analyzing the Forging of a "Viking" Sword |

|

What follows is essentially an excerpt from Joachim Kinder's

work1) entitled (translated to English) "Damascened sword blades - forged

at what temperatures for how long?" I have it under "pattern welding" and not under "Viking swords" because they are not yet typical Viking all-steel swords.

Kinder

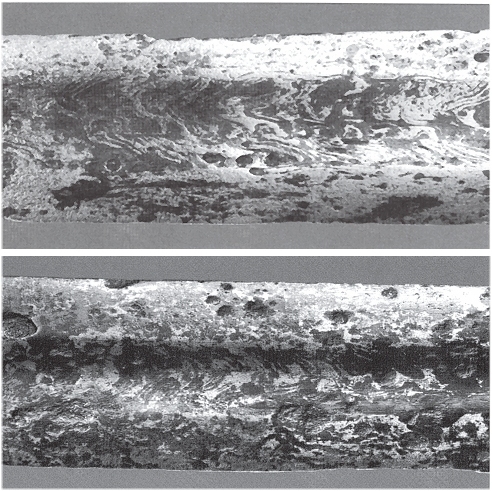

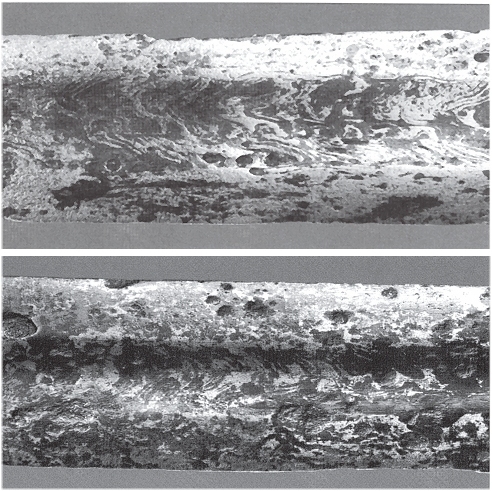

investigated two remarkably well-preserved blades that were found in the Rhine around 1920. The swords are of the Viking

type and pattern welded; they thus date to about 900 AD or somewhat later. One of the swords is now privately owned, one

is in the Tower museum in London. The swords are extremely well preserved; here are pictures of sections of the blades: |

|

| |

|

|

| | Parts of the swords |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

One of the swords had a well-defined pattern, the pattern on the other one looked

a bit "washed out".

Kinder worked at the (huge) "Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und -prüfung"

(BAM) in Berlin when he investigated these swords and had about every known analytical method at his disposal, including

a scanning electron microscope that could accommodate a whole

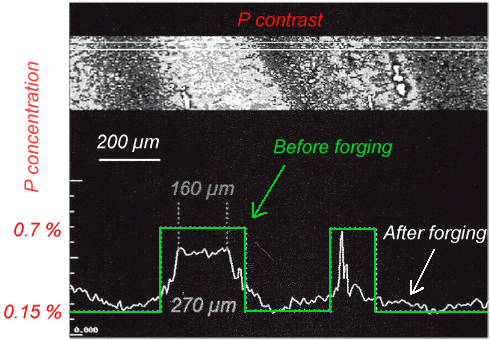

sword! He established that the contrast between the dark and bright steels involved phosphorous (P) and set out to determine

phosphorous (P) concentration profiles across weld lines with an accuracy that would allow him to determine to what extent

phosphorous had moved from the P-rich region to the P-poor region. Given the known parameters of P

diffusion that would enable him to find out what kind of temperatures the blade had "seen" for how long or,

in other words: exactly how the smith had done the forging of the blade. |

|

Interesting (and not fully understood) first results were: |

|

|

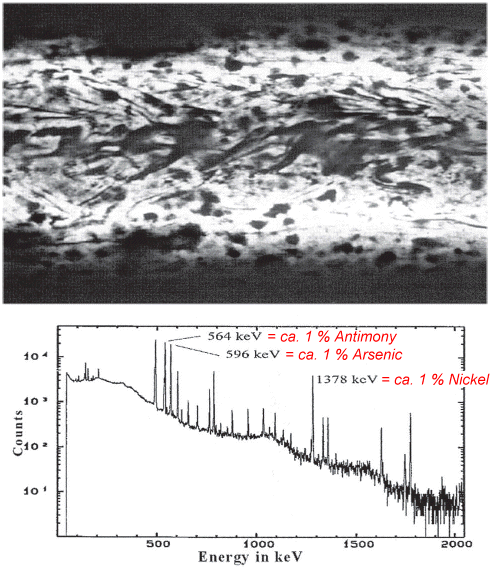

X-ray investigations showed a lot of structure and thus a lot of non-uniformity (see below).

Remember that the internal structure of a perfect straight or twisted striped rod would not

show up in X-rays pictures since all steels look very much the same to X-rays. If one

sees something, it must be due to imperfect (or corroded) welds, slag particles, holes, oxide particles, flux particles,

whatever - but not to different grades of the steel. |

| |

|

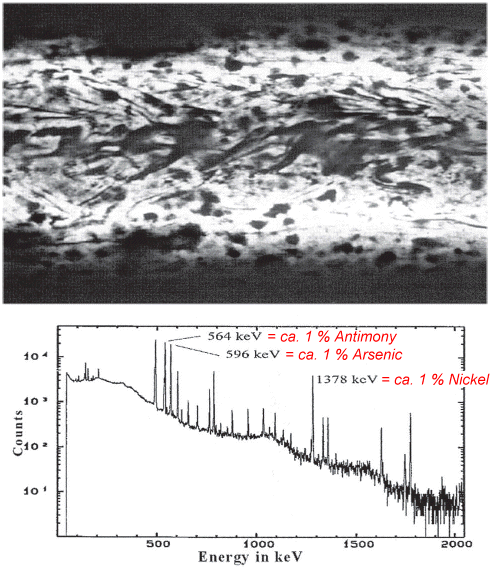

A g-ray activation analysis (you need a nuclear reactor or a substantial

particle accelerator for doing this) showed that the blades contain about 1 % of antimony (Sb), arsenic (As) and nickel

(Ni), respectively; see below. That can be seen as a clear indication

that the smith used some kind of iron - arsenic/antimony alloy with a low melting point as "flux" for joining

iron / steel by hammer welding. Note that these elements would be missed by some other analytical methods. They did not

show up, indeed, when probed with EDX |

| |

|

|

|

| Top: X-ray image of one sword

Bottom: Activation analysis spectrum showing Sb, As and Ni (among other more "normal" elements) |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

The twisted pattern is still is clearly visible on the blades since the P-rich parts are hardly

corroded at all and even "blued" by oxidation. That probably happened during the last 1000 years but it might

also be original. |

| |

| |

| |

| | Appearance of blade at low magnification

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

The phosphorous concentration varies between about 0.15 % and 0.7 % from "dark"

to "bright" stripes. The concentration profile could be imaged and measured with EDX: |

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

A detailed analysis of all the data lead to the following final conclusion:

- Fire welding took place around 1100 oC (2012 oF); i.e. at a temperature too

low for the "normal" SiO2 flux.

- The phosphorous distribution can be explained by assuming that the blade experienced an average

temperature of 975 oC (1787 oF) for 14 hours. At 1100 °C a time of 1.5 hrs would be enough. This

allows to make an educated guess at how the cycling between welding at high temperatures and forging around 850 oC

(1562 oF) must have taken place.

- About 175 heats were needed to forge the blade.

- Keeping the blade just a few more minutes at welding heat than absolutely necessary will produce a washed-out pattern

as seen on one of the blades.

- If only the carbon concentration would have been different in the layers of a striped rod, there would be no pattern

whatsoever. The carbon concentration would have completely equilibrated throughout the layers of the striped rod. Well -

we knew that!

|

| |

| |

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)