|

11.5.3 Forging a Wootz Sword |

| |

Early Wootz Swords |

|

Let's engage in our stupid little game once more: |

| |

|

Who made the first wootz sword with a nice patterned blade?

When and where?

|

|

|

|

Like always, it is a tricky question with no definite answer. First I will make

clear what I did not ask:

- I did not ask who made the first blade from crucible steel.

That happend probably much earlier. But blades made from crucible steel do not necessarilly show a pattern. The "Ulfberht's" possibly made from crucible steel around 1000 AD did most certainly not show a pattern. That can be deduced from their microstructure.

- I did not ask who made the first blade from crucible steel that showed some pattern by accident. Any UHCS, as we have seen, will

easily produce some pattern - but not necessarily a nice one.

- I did not ask who made the first blade from crucible steel that could

have shown a nice pattern if properly etched. It is conceivable that smiths made blades with the proper banded cementite

structure for a nice pattern without having been aware of that. Since rather special

forging techniques are needed, it doesn't appear to be very likely, though.

The question is thus only about the smith who conscientiously forged a blade and

finshed it with the intent of making a nice pattern.

There is of course no definite

answer to this question. We can be rather sure that "pattern forging" evolved over many years, from a process

where blades with some pattern were created more or less accidentially, to a process where materials and forging techniques

were optimized. That took many steps and the process of making blades with a nice pattern probably required a century or two for maturing.

|

|

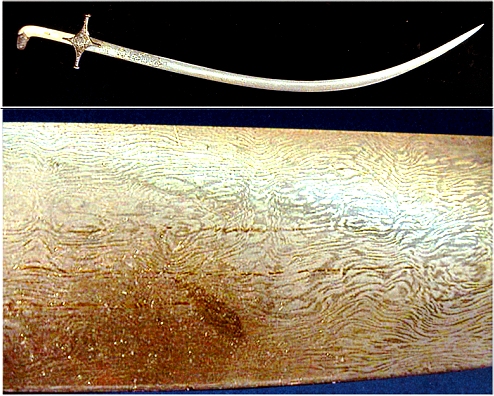

The first blades with (very) nice patterns shown in Khorasani's

magnificient book are from the Timurid period 1370 AD - 1500 AD. Here is one: |

| |

|

|

The patterns on the shamshirs shown are so perfect that they must have been based

on an older tradition. While quite likely older blades with a nice pattern exist somewhere out there, I have yet to see

one. So for answering our question we must turn to early writings. |

|

|

I have already done this in the special

module "Antique Texts Concerning Crucible Steel " There you can read that Al-Kindi (ca. 800 AD - 873 AD) mentions that swords made from pulad (=wootz) exhibt a pattern (known

then as "firind" or "jawhar") and that might be the first description of the "water" pattern

obtainable with some crucible steel,

Then we have AI-Biruni

(973 AD - 1048 AD) who also comments on the "water" pattern that could be produced with crucible steel. And so

on. |

|

|

We also have Anna

Feuerbach's analysis of a few old blades from the 3rd–4th century AD that were made from crucible steel that sported

aligned spheroidal cementite, the metallographic feature needed for a nice visible pattern. It is not clear, however, if

the smith was intentionally going for a pattern and what it would have looked like.

All things considered we might

be justified in assuming that blades with a nice pattern have been around a least since

800 AD. Perhaps even somewhat longer but probably not much longer because in many much older documents from India, crucible

steel and patterned swords are never mentioned.

That opens the interesting questions if one of the most famous swords

in history, the Zulfiqar of the Prophet Mohammed, was a wootz blade? |

|

|

| |

|

| |

Making a Mohammed's Ladder |

|

From the preceding modules it should be rather clear how a "normal"

wootz blade was forged. The key points were:

- Start with a suitable "wootz cake" or "bulad

egg". It needs to be a high carbon steel, homogenous without slag inclusions, and preferably with traces of strong

carbide formers like vanadium (V); some manganese (Mn) wouldn't hurt either.

- Spheroidize the cementite

if that has not already happened during the cooling of the crucible steel. It is not clear (to me) if the ancient smiths

used some special procedure for doing that right at the beginning of the blade forging or if spheroidization happened as

a by-product of the forging process.

- After spheroidization you must keep the temperature rather low. If the blade ever gets above the A1 temperature for some time, all is lost.

- The necessary Ostwald ripening demands several temperature

cycles between just above the ferrite - austenite transformation temperature around 730 oC (390 oF)

for just the rigth time. That may just happen by the forging process itself if done just right.

Depending on all the details, you end up with a wootz blade that shows one or the other of the less intricate patterns. |

|

|

But now we want to make a step

pattern, better known as kirk nardeban" or Mohammed's

ladder with "roses"

in it.

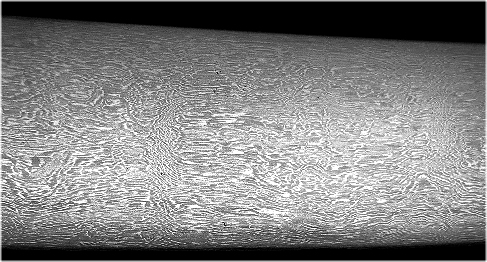

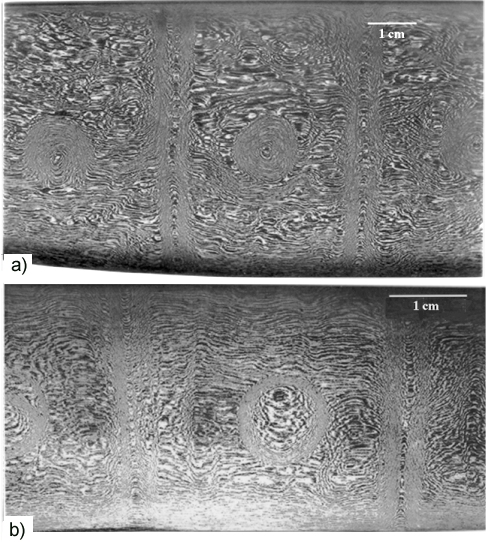

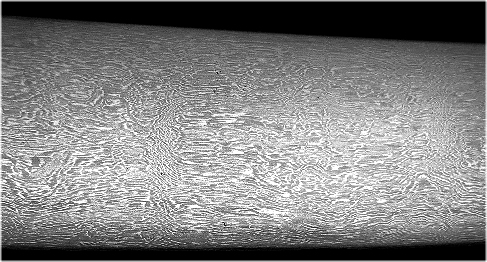

The picture below (from am Indian wootz blade in my possession) shows a few weak "steps". The smith

has made an attempt at a kirk nardeban pattern and succeeded for some ladder rungs in parts of the blade but not everywhere. |

| |

|

| Three faint rungs of a kirk nardeban pattern |

|

|

|

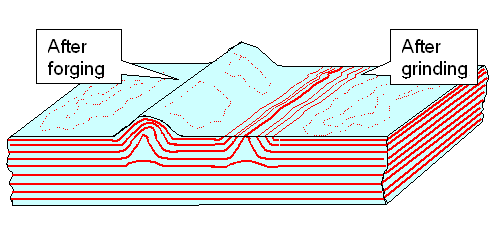

How is it done? The principle is easy. Make a hump in the otherwise somewhat wobbly but planar

stack of your cementite precipitate planes. Schematically (very schematically, I'm not an artist) you could produce something

like this: |

|

|

|

|

|

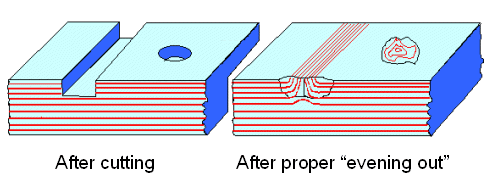

What also works is to cut grooves as shown below, followed by the more tricky part of "filling

" them again, This "evening out" the blade must be done in such a way that the cementite planes are arranged

as shown. |

|

|

|

|

You might also make grooves by cutting with a chisel and God

smiths know in how many other ways. That this works has been demonstrated by Al Pendray, his results are shown here and below I show them again: |

| | |

|

|

I really don't know how you do all this in detail - ask

a smith! The only problem is that there aren't too many around right now who could tell you. And the few who could will

probably keep their mouths shut.

Anyway, the principle of manipulating wootz patterns is clear. The principle for making

a major marble sculpture like this one is also quite

clear: Take a big piece of marble and knock off whatever is not needed. |

|

|

The guy who makes a great marble

sculpture we call an artist, and his work a piece of art. I do not hesitate to call a smith who makes a wootz sword

like the ones shown here an artist too, and his work a piece of art. And now we are right back to the beginning of this hyperscript, far, far away. |

| |

|

| |

The Myth Around Wootz

Swords |

|

Wootz swords with a nice "water" pattern were supposed to be unbelievably

good, far better than anything else. A whole mythology developed around this. Since the "Japanese sword" enjoyed

the same mystification process, I won't go into much details here but do that in the next module.

Wootz swords, for

example, were believed to be unbelievably sharp. You even could cuts stones with a wootz blade without the slightest damage

to the blade. And of course you could bend them around your waist without any problems. |

|

|

We have encountered some of these claims before:

- In this link Sultan Saladin cuts a soft silk cushion with

his wootz scimitar.

- Here the (wootz) blade is "bent

around the body of a man and breaks not". The author of this contribution actually makes fun of the wootz mythology

but must have based his satire on the claims he encountered around 1890.

- In this module a stone is cut in half by a wootz blade wielded by

one of Germany's biggest if fictive hero.

|

|

Of course, the mythology around wootz swords owns quite a bit

to all the early and later

writings concerning the "secret" of the Indian steel, and to the fact that crucible / wootz steel was indeed better

in some respects than other old steels throughout the millennia. No doubt about that.

However, even the best wootz is just a (ultra) high carbon steel, and even with spheroidized cementite this steel has its

limitations.

How good wootz (or "true" damascene) blades really are is something one can find out. Prof. Zschokke (an early metallurgist from Switzerland) was lucky enough

to get a few wootz blades for (destructive) investigations. This is quite unusual because these blades are valuable and

museums and collectors do not easily agree to have some of them destroyed.

Manfred Sachse in his book reports some of Zschokke's results. Here are a few: |

| |

| General composition |

| Sample |

[C] |

[Si] |

[Mn] |

[S] |

[P] | | 1. Wootz Saber |

1.874 | 0,049 | 0,005 | 0,013 |

0,127 | | 2. Wootz Saber | 0,569 |

0,119 | 0,159 | 0,032 | 0,252 |

| 3. Wootz Saber | 1,324 | 0,062 | 0,019 |

0,008 | 0,108 | | 4. Wootz Saber |

1,726 | 0,062 | 0,028 | 0,020 |

0,172 | | 5. Modern welded steel saber |

0,606 | 0,059 |

0,069 | 0,007 |

0,024 | | 6. Modern cast steel saber |

0,499 | 0,518 |

0,413 | 0,038 |

0,045 |

|

| |

| Properties |

| Sample |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 | | Bending toughness |

13,4 | 15,2 | 11,5 | 14,5 |

21,6 | 30,0 |

| Work to bend | 94 | 221 | 55 |

63 | 361 | 622 |

| Angle of bending | 27 | 59 | 19 |

17 | 69 | 78 |

| Hardness | 216 | 233 | 193 |

248 | 347 | 463 |

|

|

|

Specimen 1 - 4 were wootz blades, 5 and 6 were modern early 20th century welded and cast steel

blades from Solingen. They were the winners in every category. |

|

Nothing very special or very good about wootz blades. Well, we already know that

from what I have written before. You can also read a short

article from Stephan C. Alter from 2017, entitled:

"On Slaves and Silk Hankies. Seeking Truth in Damascus Steel" that puts all these myths in perspective. |

| |

|

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)