|

So far we have only considered one conducting

material; the unavoidable contacts between conductors, implicitly always

required, were seemingly devoid of special properties. |

|

|

We know that this is not true for many other

contacts; e.g. combinations of - semiconductor - semiconductor.

- semiconductor - conductor.

- ionic conductor - conductor.

|

|

|

What about metal - metal contacts? |

|

We routinely solder wires of different conductors together or join them in any way, and do

not worry about the contacts. Besides, maybe, a certain (usually small) contact resistance

which is a property of the interface and must be added to the resistance of the two materials, there seems to be no other

specific property of the contact. |

|

|

But that is only true as long as the temperature

is constant in the whole system of at least two conductors. |

|

|

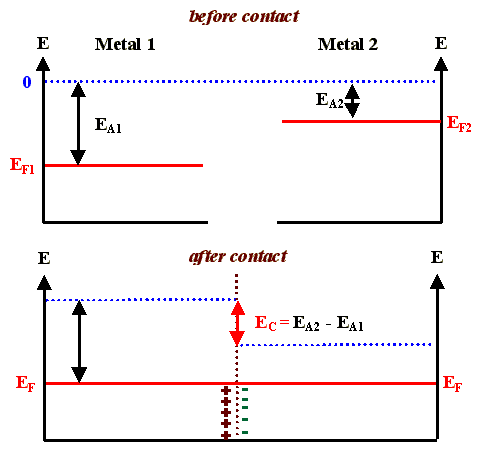

The reason for this is that we always get a contact voltage, as in

the case of semiconductors, but the extension of the charged layers at the interface (the Debye

lengths) is so short that no specific phenomena result from this. |

|

|

Consider the band diagrams before and after joining two metals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

We have a dipole layer of charges at the interface which, owing to the large carrier

density, is extremely thin and does not hinder current flow (it is easy for electrons

to tunnel through the potential barrier). |

|

|

We also have a contact potential, which is called the

Volta

potential. Since in any closed circuit (containing, e.g., the wires to the voltmeter),

the sum of the Volta potentials must be zero in thermal

equilibrium, it therefore can not be measured directly. |

|

|

If, however, one of the at least

two contacts needed for a closed circuit is at a temperature T2 that is different from the temperature

T1 of the first contact, we have non-equilibrium and now a

voltage may be measured. We observe the Seebeck

effect, one of several thermoelectric effects. |

|

We will not go into details here (consult the

link for this) but will only mention some applications and related effects. |

|

|

|

Seebeck Effect |

| | |

|

The Seebeck effect is the base for thermoelements

or thermocouples, the standard device for measuring temperatures (the good old mercury

thermometer is virtually nonexistent in technical applications, especially at high temperatures). |

| |

|

| |

|

|

Lets look at a typical situation: We have a thermocouple mader with a material 1 and

a material 2. It's "contacted" by whatever (material 3, black lines). The junction of material1

and material 2 is hot, the rest is cold (and has the same temperature). |

| | |

|

The voltmeter will show a thermovoltage that depends on DT

and the two materials forming the thermocouple. |

| |

| | |

|  |

Generally, the thermovoltage should be larger for couples of conductors with very

different Fermi energies or carrier densities, since then the Volta potential is larger. |

|  |

Being more specific, the Volta potential should follow Nernsts

law. But here we are only interested in the practical aspects of thermocouples. |

|

For technically important materials, it is convenient to construct a voltage scale for thermocouples

given in mV/100K. |

|

|

The voltage measured for a temperature difference of 100 K is then the difference of

the two values given on that scale for the two materials joined in a thermocouple. The zero point was arbitrarily chosen

for Pt. |

| |

| Bi | Ni | Pd |

Pt | Hg | PtRh |

Cu | Mo | Fe |

NiCr | Sb | | -7,7 |

-1,5 | -0,3 | 0 |

0 | 0,7 | 0,77 |

1,2 | 1,92 | 2,6 |

4,8 |

|

|

|

Useful couples are, e.g. Ni/NiCr, with a thermovoltage of ca. 4 mV/100K and a

usable temperature range up to 1000 K. |

|

The Seebeck effect, for many years extensively used for measuring temperatures, can also be

used to convert heat energy directly into electrical energy. Thermoelectric generators

are becoming an exciting field of materials science, because optimized materials, based on a thorough understanding of the

requirements for power generation and the concomitant requirements for the materials, are becoming available. |

| |

|

Other Thermoelectric Effects |

| | |

|

There are several thermoelectrical effects which are deeply routed in non-equilibrium thermodynamics. Essentially, there is a "reciprocating"

coupling of gradients in driving forces and currents of any

kind (not just electrical currents but also, e.g. particle currents, heat currents, or even entropy currents).

|

|

|

|

Reciprocating means, that if a gradient

- e.g. in the temperature - induces an electric current

across a junction (the Seebeck effect), than an electric current induced by some other means

must produce a temperature gradient. And this does not address the heating simply due to ohmic heating!

|

|

|

|

The "reversed" Seebeck effect does indeed exist, it is called the Peltier

effect. In our schematic diagram it looks like this: |

| | |

|

|

| |

|

|

An electrical current, in other words, that is driven through the system by a battery, would

lead to a "heat" current, transporting thermal energy from one junction to the other one. One junction then goes

down in temperature, the other one goes up. |

|

This effect would also occur in hypothetical materials with zero resistivities (we do not mean superconductors

here). If there is some resistance R , the current will always lead to some heating of the wires everywhere

which is superimposed on the Peltier effect. |

| |

| | |

|

|

|

The temperature difference DT between the two junctions

due to the external current density j induced by the battery and the Peltier effect then is approximately given by

|

| |

|

|

|

The removal of heat or thermal energy thus is linear with the current density |

|

|

But there is always heating due to by ohmic losses, too. This is proportional to j2,

so it may easily overwhelm the Peltier effect and no net cooling is observed in this case. |

|

The Peltier effect is not useful for heating - that is

much easier done with resistance heating - but for cooling! |

|  |

With optimized materials, you can lower the temperature considerably at one junction by simply

passing current through the device! The Peltier effect actually has been used for refrigerators, but now is mainly applied

for controlling the temperature of specimens (e.g. chips) while measurements are being made. |

|

One can do a third thing with thermoelements: Generate power. You have a voltage coupled to

a temperaturr difference, and that can drive a current through a load in the form of a resistor. |

| | |

| |

|

|

|

|

Invariably the question of the efficiency h of power generation

comes up. How much of the thermal energy in the system is converted to electrical energy? |

| | |

|

This is not eays to calculate. It is, however, easy to guess to what h

will be proportional: |

|

|

| | |

|

There is one more effect worthwhile to mention: If you have an external current and

an external temperature gradient at the same time, you have the Thomson

effect. But we mention that only for completeness; so far the Thomson effect does not

seem to be of technical importance. Again, more information is contained in the

link. |

|

|

© H. Föll (Electronic Materials - Script)