|

Formulas here have plenty of indices, underlining etc. - and we will

now give up the cursive font normally used for variables because it gets too cumbersome. |

| |

|

Basic Idea |

| |

|

The Coincidence Site lattice (CSL) provided

a relatively easy way to grasp the concept of special orientations between grains that give cause for special grain boundaries.

With the extension to grain boundary dislocations in the DSC lattice, the CSL concept became in principle

applicable to all grain boundaries, because any arbitrary orientation is "near" a CSL orientation. But

yet, the CSL concept is not powerful enough to allow the deduction of grain boundary structures in all possible cases.

The reasons for this are physical, practical and mathematical: |

|

|

The CSL by itself is meaningless; meaningful

is the special grain boundary structure that is possible if there is a coincidence orientation. The grain boundary structure

is special, because it is periodic (with the periodicity of the CSL) and contains coincidence points (cf. the picture). |

|

|

But we have no guarantee that periodic grain boundary structures may not exist in cases where no CSL

exists; i.e. by only looking at CSL orientation, we may miss other special orientations.

That will be certainly true whenever we consider boundaries between different lattices - be it that lattice constants of

the same materials changed ever so slightly because one grain has a somewhat different impurity concentration, or that we

look at phase boundaries between different crystals. If the lattice constants are incommensurable, there will be no CSL

at all. |

|

|

As we have seen, even a CSL with S = 41 is significant, even so

it is virtually unrecognizable as anything special in a drawing. This is an expression of the mathematical condition, that

you either have perfect coincidence or none. If two points coincide almost, but not quite, no recognizable CSL will

be seen. If two lattice points coincide except for, lets say, 0,01 nm, we certainly would say we have a physical

coincidence, but mathematically we have none. |

|

|

The same is true if we rotate a lattice away from a coincidence position by arbitrarily small angles. Mathematically, the coincidence is totally destroyed and the situation has completely changed,

whereas physically an arbitrarily small change of the orientation would be expected

to cause only small changes in properties. |

|

|

Only a very small fraction of grain orientations have a CSL. The "trick" we used to transform

any orientation into a coincidence orientation by introducing grain boundary dislocations in the DSC lattice is somewhat

questionable: the effect (= CSL) comes before the cause (= dislocations in the DSC lattice), because at the

orientation that we want to change no CSL and therefore no DSC lattice exists. |

|

It becomes clear that the main problem lies in the discreteness of the CSL. Any useful

theory for special grain boundary (and phase boundary) structures must be a continuum

theory, i.e. give results for continuous variations of the crystal orientation (and lattice type). |

|  |

This theory exists, it is the so-called "O-lattice theory"

of W. Bollmann; comprehensively published in his opus magnus

"Crystal Defects and Crystalline Interfaces" in 1970. |

|

|

The O-lattice theory is not particularly easy to grasp. (Sorry,

but it took me many hours, too). It is well beyond the scope of this hyperscript to go into details. What will be given

is the basic concept, the big ideas; together with some formulas and a few examples. You should first read just over it,

trying to get the basic ideas, than study it point by point. If you don't get it the first time - don't despair, you are

in good if not excellent company! |

|

There are two basic ideas behind the O-lattice theory: |

|  |

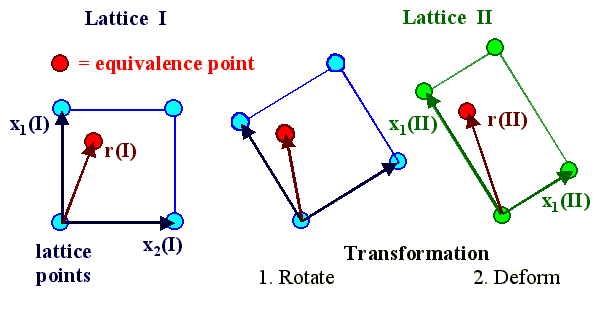

1. Take a crystal lattice I and transform it in any way

you like. That means you can not only rotate it into an arbitrary orientation relative to crystal I, but also deform

it by stretching, squeezing and shearing it. The crystal lattice II generated

in this way from a simple cubic lattice I thus could even be an arbitrarily oriented triclinic lattice. |

|

|

2. Now look for coincidence points between lattice I and lattice II. But do not restrict

the search for coinciding lattice points, but expand the concept of coincidence to all

"equivalence points" within two overlapping unit cells. What equivalence points are becomes clear in the illustration. |

|

|

|

|

|

Points in lattice I and lattice II are called equivalent, if their space vectors

are identical (always in their respective lattice coordinate system). |

|

| |

|

Let's look at the example illustrated above. Lattice I is deformed by first

rotating it and then stretching the axis x1; this produces lattice II |

|

|

An arbitrary point within the elementary cell of lattice I is described

by a vector r(I) |

|

|

r(I) transforms into a vector r(II) by the transformation applied.

The point reached within the unit cell of lattice II by r(II) is then an equivalence

point to the one in crystal I. |

|

Of course there is more than one equivalence point; there is always an infinite

set defined by one point plus all points reachable

by a lattice translation vector T from this particular point. |

|

|

Any point r'(II) in lattice II belonging to the set as defined above

can be described in the coordinate system of lattice II (defined by the units vectors x1(II)

and x2(II)) by |

|

|

|

|

|

With T(II) = any translation vector of lattice II, or |

| |

| T(II) | = |

n · x1(II) + m · x2(II) |

|

|

|

|

And n, m = 0, ± 1, ± 2, ... |

|

All these points are by definition

equivalence points to the corresponding set of points

in lattice I given by |

| |

|

|

Let us designate the set of all equivalence

points defined above in lattice I by C1 and the corresponding

set in lattice II by C2 and, for the sake of clarity, all vectors

pointing to equivalence points of the respective sets by r(C1) and r(C2). |

|

If we now look at a certain equivalence point in lattice II, it always

originated from lattice I by the general transformation as shown in the picture below |

| |

|

|

The blue lattice was obtained from the pink one by some transformation; in this

case by a simple rotation. |

|

|

The dark point with the red vector pointing to it is an arbitrary point in lattice I

(for the sake of easy recognition about in the center of a lattice I cell). |

|

|

After the transformation, it is now the red point at the apex of the blue and pink arrows

in lattice II. It is still about in the center of a cell in lattice II, but for the particular

transformation shown, it is now also about in the center of a lattice I cell - there is (about) a coincidence

of equivalence points. |

|

|

Let's assume perfect coincidence, then the red point denotes coinciding

equivalence points, i.e. equivalence points that are "on top of each other". |

|

We need a precise mathematical formulation that gives us the conditions under

which coincidence of equivalence points occcurs. |

|

|

This is easy, we just have to consider that for coinciding equivalence points the blue vector

in lattice II can be obtained in two ways:

- By the transformation equation from the corresponding red vector of lattice I (valid for all

equivalence points) or, since the coincidence point belongs to both lattices at once, by

- adding some translation vector of lattice I to the red vector. This is symbolically shown in the picture.

|

|

|

In formulas we can write for any vector in lattice II

pointing to some equivalent point of the set C2: |

| |

| r(C2) | = |

A {r(C1)} |

| | | |

| r(C1) | = |

A–1 {r(C2)} |

|

|

|

|

With A = transformation matrix (we will encounter

examples for A later; see also the basic module for

matrix calculus) since this simply describes how lattice II originates from lattice I. This was the first

way mentioned above. |

|

|

On the other hand, we can obtain new equivalence points in lattice I, i.e. other elements

of the set C1 designated by e(C1) quite generally by the equation |

| |

|

|

|

We will now use these relations for coinciding equivalence points: |

|

We are looking for coincidences of any one member of the set r(C1)

with any one member of the set r(C2); any coincidence point thus obtained will be named r0.

Since this point, describable in lattice II by r(C2) must be reachable in lattice I by first

going down r(C1) and then adding a translation vector of lattice I, we obtain |

| |

|

r(C2) = r(C1) + T(I) = r0 |

|

|

|

|

Using the transformation equation for lattice I from above and substituting it into the above equation yields

|

| |

|

|

|

We wrote r0 instead of r(C2) because we

do not need the distinction between the sets C1 and C2 any more because r0

belongs to both sets. |

|

|

Rearranging the terms following matrix

calculus by using the identity or unit transformation matrix I, we obtain

the fundamental equation of O-lattice theory: |

| |

|

|

What does that equation mean? |

|

|

For a given transformation, i.e. for given orientation relationship between two grains, its

solution for r0 defines all the coincidence points or O-points of

the lattices. The coincidence of lattice points is a subset of the general solution for the coincidence of equivalence points. |

|

|

The question comes up if there are any solution of this equation. Algebra

tells us that this requires that the determinant of the matrix, |I – A–1|, must be ¹ 0.

This will be generally true (but not always), so generally we must expect that solutions exist, i.e. that a CSL (=

O-lattice) for some equivalence points (= O-points) exists - for any possible combination of lattice I

and lattice II. |

|

How do we solve the O-lattice equation, i.e. obtain the set of O-points for a

given lattice and transformation? Simply by inverting the matrix we obtain: |

|

|

|

r0 = ( I – A–1 )–1

· T(I) |

|

|

|

That is all there is to do; it looks easy. If we have a given transformation matrix A, the equation above gives us the set of vectors defining the equivalent points, or as we are going to

call them, the O-points of the two lattices. |

|

|

However, the diffusion equations look easy, too, but are not easy to solve. Also, we do not yet know what

the solution, the O-lattice, really means with respect to grain- or phase-boundaries. |

|

We will look at this more closely in the next paragraph; but first we will discuss a simple

example. |

| |

|

To keep the matter simple, we look at a two-dimensional

situation where a square lattice rotates on top of another one. This will include our former example of the S = 5 CSL case. (A word of warning: In Bollmanns book are occasional

mistakes when it comes to the S5 orientation (which is frequently used for illustrations)). |

|

|

The transformation matrix is a pure rotation matrix, for the rotation angle a

it writes |

| |

| A | = |

æ

è |

| cos a |

– sin a |

| sin a |

cos a |

| ö

ø |

|

|

|

|

From this we get |

| |

| A–1 |

= | æ

è

|

| cos a |

sin a |

| – sin a |

cos a |

| ö

ø | |

| 1 – A–1 |

= | æ

è

|

| 1 – cos a |

– sin a |

| sin a |

1 – cos a |

| ö

ø | |

| (1 – A–1 )–1 |

= | æ

è

|

| ½ | |

– ½ cotan a/2 |

| ½ cotan a/2 |

| ½ |

| ö

ø |

|

|

|

Now let's do an example. The base vectors of the square lattice I are x1(I)

= (1, 0), x2(I) = (0, 1). |

|

|

If we use them as the smallest possible translation

vector T(I) of lattice I, we obtain by multiplication with the last matrix the smallest

vectors of the O-lattice which then must be the unit vectors of the O-lattice,

u1 and u2: |

|

|

| u1 | = |

æ

ç

è |

½

½ · cotan (a/2) |

ö

÷

ø |

| | | |

| |

| | | |

| |

| u2 | = |

æ

ç

è |

– ½ · cotan (a/2)

½ |

ö

÷

ø |

|

|

|

|

This is easily graphically represented, but the pictures get to be a bit complicated: |

| |

|

|

Lattice I is the blue lattice, lattice II the red one; it has been rotated by

the angle a. |

|

|

The unit vectors of the O-lattice can be determined by the intersection of the light-

and dark-green lines (remember the definition of tan and cotan!); they are depicted in black. |

|

|

The O-lattice then can be constructed, its lattice points are shown as orange blobs. |

|

Note that a three dimensional expansion would not produce much that is new. On any plane above

or below the drawing plane, the situation is exactly what we have drawn. This has one interesting consequence, however: |

|

|

In three dimension, we have no longer O-points,

but O-lines in this case. |

|  |

The O-lattice in this case thus is not a point lattice, but a lattice of

lines perpendicular to the plane of rotation. This will come up naturally later, but it is good to keep it in

mind for what follows. However, since this is not the most general case, we will keep talking of O-points. |

|

The picture neatly helps to overcome a possible misunderstanding:

For any O-point, a vector from the origin of either crystal to the O-point (our vectors r(I)

and r(II)) point to a coinciding equivalence point or O-point,

but different points of the O-lattice may be different

equivalence points. In the example we have O-points that are almost at the center of both unit cells, or almost

at a lattice point of both unit cells - the O-lattice seems to be constructed of two kinds of coinciding equivalence

points; but: |

|

|

If we would include more cells of the O-lattice, we would see that equivalence points shift slightly

for the example given. A few O-lattice cells away, they would be more off-center or more distant to a lattice point

than close to the origin of the O-lattice. |

|

|

Just how many equivalence points of the set of equivalence points (which

has an infinite number of members) are needed for an O-lattice is an important (nontrivial) question which we will

take up later again. |

|

We can rephrase this important question:

|

|

|

Is the pattern of equivalence points periodic (= finite number of equivalence

point) or non-periodic (infinite number)? In other words: If any one point of the O-lattice

defines a specific equivalence point in the crystal lattices, does this specific point appear again at some other point

in the O-lattice (apart from the trivial symmetries of the O-lattice)? |

|  |

We will come back to this question later; it is the decisive

feature of the O-lattice for defining the DSC-lattice. |

|

How do we get the CSL from the O-lattice? That is easy: It must

be that particular subset of all possible O-lattices where all O-points are also lattice points in both lattices. |

|

|

Looking at the unit vectors of the O-lattice, however, there is no way of expressing them in integer

values of the base vectors of lattice I, because one component is always 1/2. How about that? |

|

This is not a real problem, best illustrated with an example: If we chose a

= 36o52,2', we have |

| |

| u1 | = |

æ

ç

è |

½

½ · cotan (a/2) |

ö

÷

ø |

= |

æ

ç

è |

1/2

3/2 |

ö

÷

ø |

| | | |

| |

| |

| |

| | | |

| |

| |

| |

| u1 | = |

æ

ç

è |

– ½ · cotan (a/2)

½ |

ö

÷

ø |

= |

æ

ç

è |

– 3/2

1/2 |

ö

÷

ø |

|

|

|

|

Thus every second point of the O-lattice is a lattice point

in both lattices (depicting O- points of the equivalence class [0,0]), these points thus define the S = 5 CSL. The other O-points are of the equivalence class [1/2,1/2]. CSL

lattices (two-dimensional case) thus correspond to specific O-lattices, but with lattice constant possibly larger

by some integer value. This is quite important so we will illustrate this

in a special module. |

|

Note, too, that in this case the pattern of equivalence point is obviously periodic, so we

have a first specific answer to the question asked above. |

|

Before we delve deeper into the intricacies of O-lattice theory, we shall first discuss

some of its general implications in the next paragraphs. |

© H. Föll (Defects - Script)