| |

|

|

Halle is a city in the southern part of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. Halle

is an economic and educational center in central-eastern Germany and the birthplace of Georg Friedrich Händel. Since

I once had close relations with the Max-Planck-Institute of Microstructure Physics in Halle, I was there a lot - and never

saw anything of the city. |

|

|

Meanwhile I changed that and I'm glad. There is a lot to see and the "Landesmuseum

für Vorgeschichte", i.e. the Museum of the German state of Sachsen-Anhalt dedicated to prehistory. It is not only

a highlight but a must for anybody interested in the stone age and early metals.

You'll find an unbelievable amount

of stone and bronze objects in mint conditions. This is mostly due to heavy surface coal digging since the 19th century

but also to some recent luck; I'll get to that. |

|

The museum is housed in an imposing early 20th century building with

large and airy rooms. Most of the objects are displayed in an old-fashioned way, meaning that not only can you actually

see the objects, there are also well-written explanations, readable without using a flashlight while lying on your belly.

Moreover, there are good models, many highly interesting maps, and fascinating artistic impressions of what things might

have looked like.

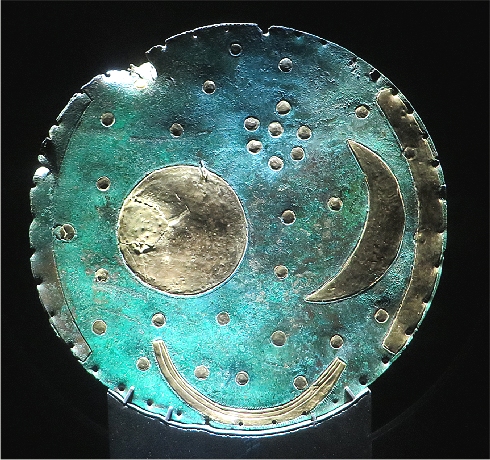

The high point of the museum is the famous "Nebra sky disk".

I have referred to it before. |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

|

|

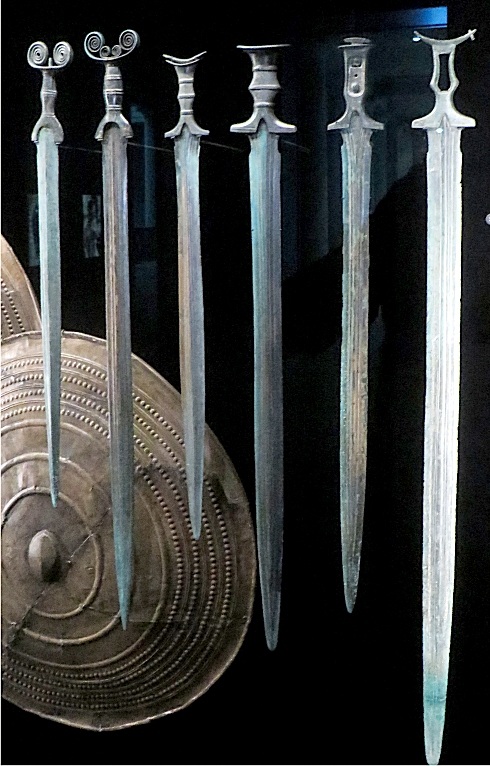

The disc is a unique one-of-its-kind object. That would be sufficient to make

it famous. It was "discovered" by treasure hunters who tried to sell it; illegally of course. Two elaborately

made bronze swords (shown here and in large scale here)

and a few smaller items completed the loot. The finders were eventually caught by international police forces in a highly

spectacular way, and the objects found their way into the museum.

The Nebra sky disc is from about 1600 BC and features

the oldest concrete depiction of the cosmos worldwide. In June 2013 it was included in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register

and termed "one of the most important archaeological finds of the twentieth century". |

|

The whole thing was a stupendous sensations with all kinds of repercussions.

The museum spared neither time nor effort to accommodate these fabulous objects in style. A special room was dedicated to

the Nebra things, and the rooms given to middle bronze age were completely redone. That's partially quite unfortunate since

the museum then succumbed to the dreaded "Keep-things-in-the-dark disease", like so many others before. While the Nebra objects are perfectly

illuminated and displayed, this cannot be said for many other things; I'll get to that. |

|

|

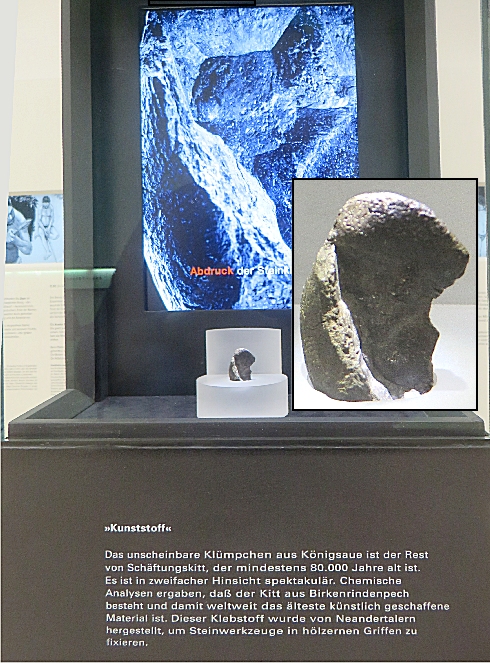

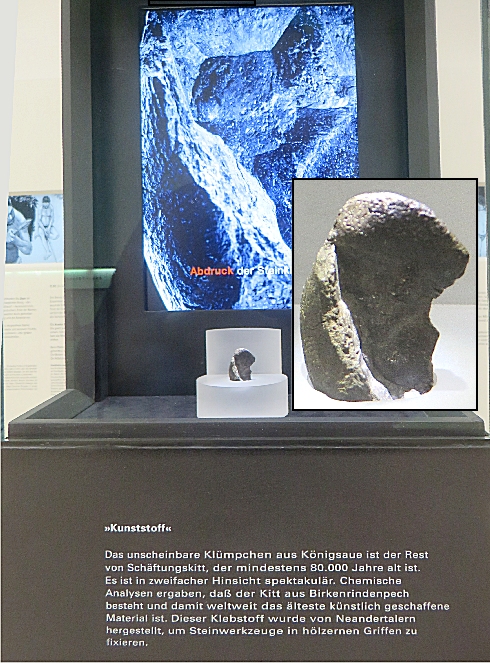

First, however, let's look at some stone age stuff. Below you see why I like

this museum so much. It gives a whole case with good explanations and pictures to a really unassuming tiny object: |

| | |

|

| |

|

|

| Birch bark tar; 80.000 years old from Neandethals |

| Source: Photographed in the Museum in April. 2018 |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Well - it's the oldest man-made material: Birch bark

tar or birch pitch. Absolutely essential to early humans. I've told you about that elsewhere.

The next example also pays tribute to the museums old but great ways of presenting their stuff. |

| | |

|

|

|

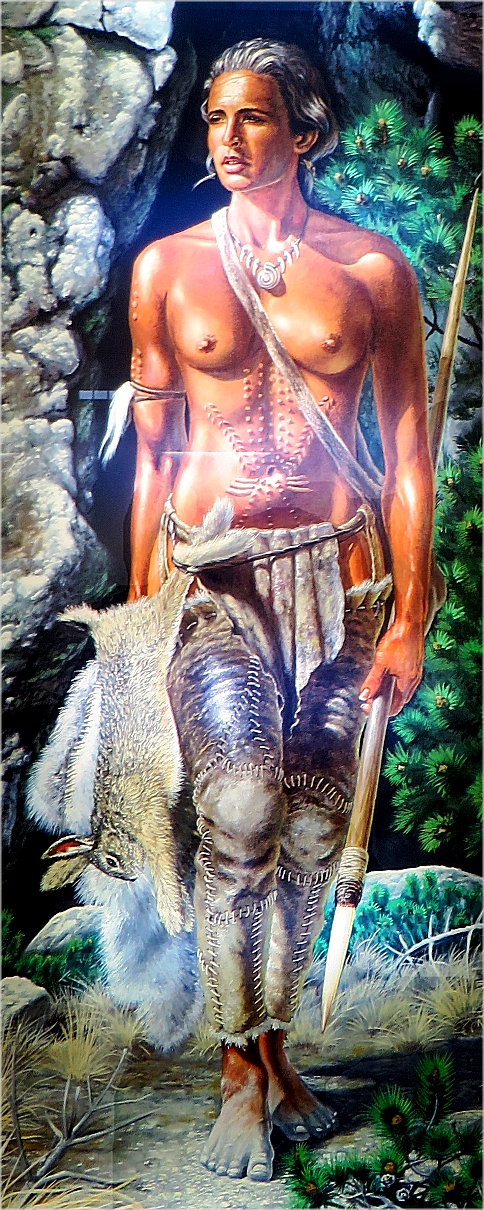

| | Woman from Bad Dürrenberg. (7.000 - 6.600 BC) |

| Source: Photographed in the Museum in April. 2018 |

|

| | |

|

|

|

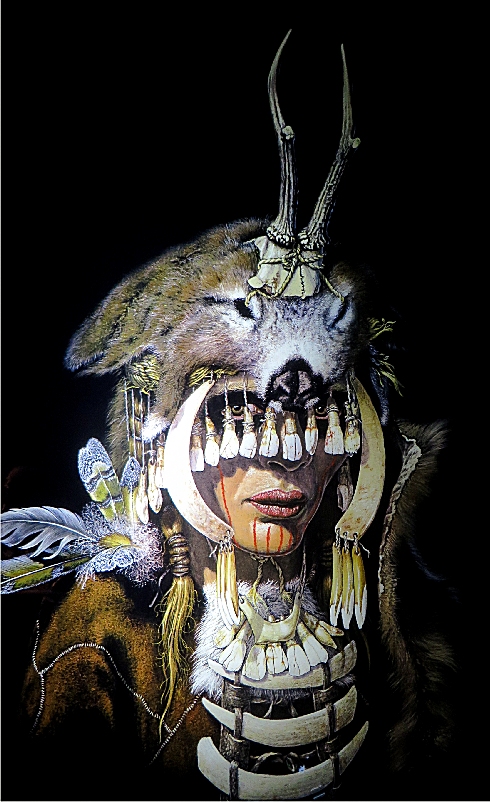

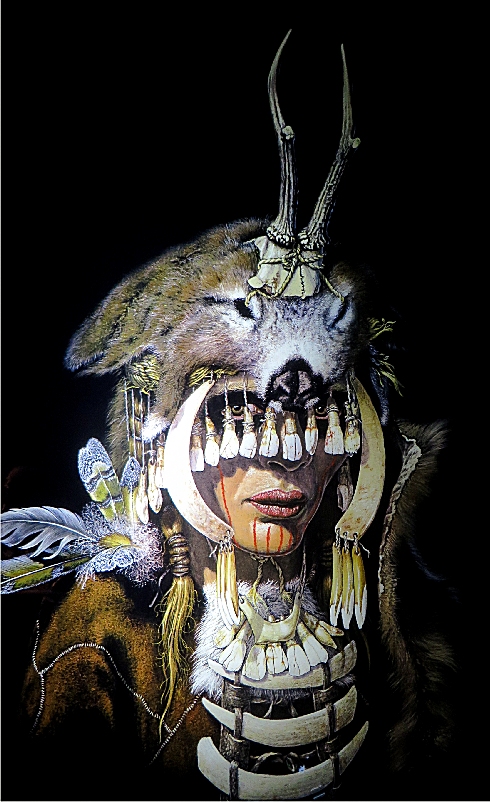

Just an elderly lady? Yes - but a special one. Read the description! The stuff

in her grave indicates that she wielded power, probably as a shaman. The close inspection of her skull indicated that she

had a kind of bone deformation that allowed her to induce semi-consciousness or trance by certain movements of her head.

Clear texts and pictures guide you through the details.

To top it off, an artists interpretation of what she might have

looked like is provided, based on some of the things in her grave, that really tickles your phantasy: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

Woman from Bad Dürrenberg. (7.000 - 6.600 BC); artists conception

Large size |

| Source: Photographed in the Museum in April. 2018 |

|

| | |

|

|

|

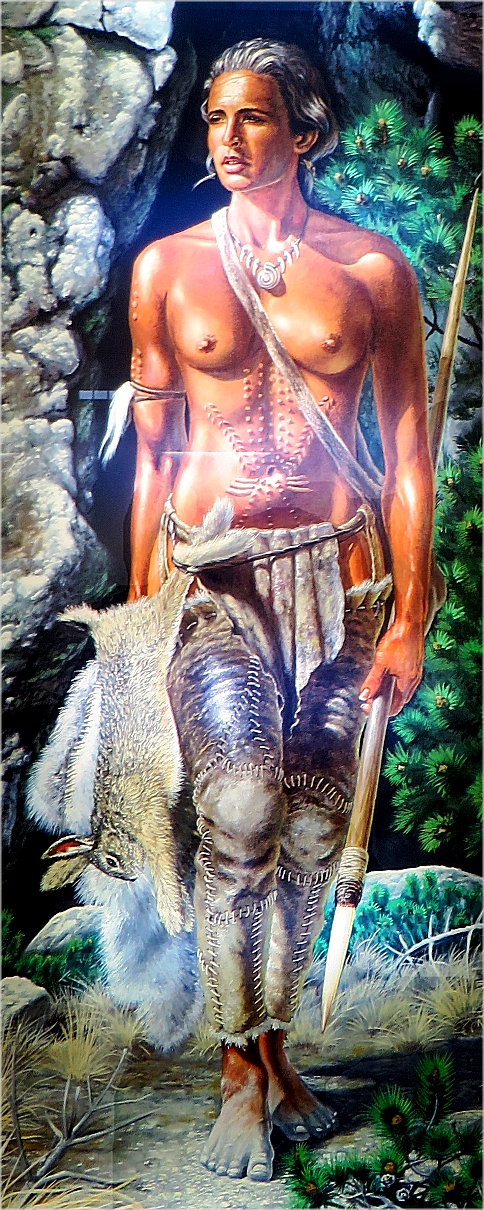

Pictures like that do help your imagination (possibly in more than one way).

That's why I give you another one: |

| |

| |

| |

|

Homo Sapiens; around 40.000 BC

Brought along some technology like designer cloth

(and good looks)

and replaced (after some mingling) the Neandethals. |

| Source: Photographed in the Museum in April. 2018 |

|

| | |

|

|

It's time for the more serious stuff. I've seen many stone axes with holes before

but never wondered how those stone age guys drilled the holes. They definitely did not have the usually assumed hollow copper drill. The museum shows and explains how

it was done. Go there yourself to find out.

It suddenly became clear to me that all that hole drilling after

copper tools became available was nothing new to the ancient artisans. They had done it before for thousands of years with

less sophisticated tools |

| |

| |

| |

|

Partially drilled stone axe and some drilling cores. 6.900 - 6.600 BC;

definitely no copper drills then. |

| Source: Photographed in the Museum in April. 2018 |

|

| | |

|

|

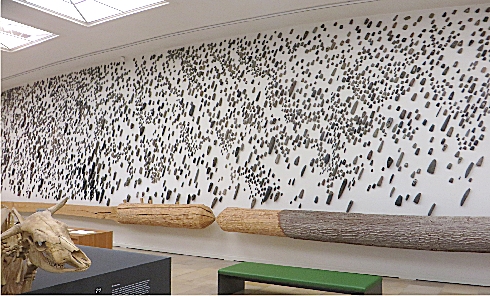

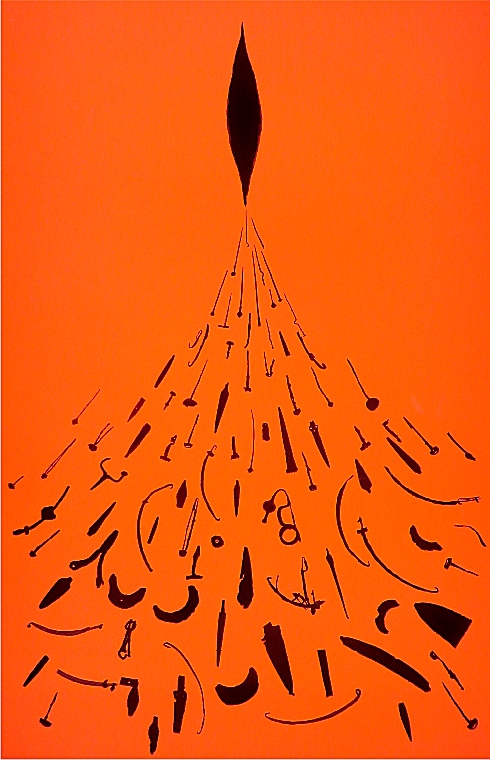

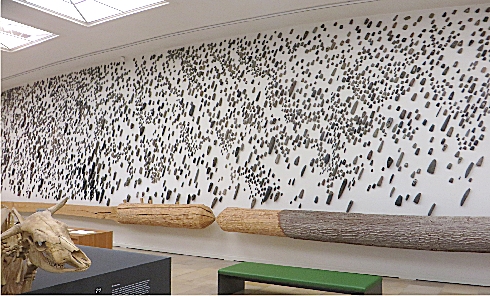

Another impressive feature is the wall of a huge room. It is covered

with many thousands of stone tools. Far better than to keep all that

in some dark basement. |

| | |

|

|

|

| Stone tools and how you work wood with them

Large size |

| Source: Photographed in the Museum in April. 2018 |

|

| | |

|

| |

|

One could spend a long time in this room alone - and I haven't

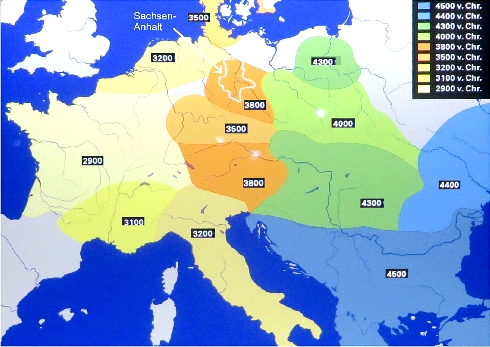

even mentioned the ceramics there and elsewhere. I learned a lot about early cultures in middle Europe, including a thing

or two about the influx of copper and bronze technology from the South-East. For example, how it spread (see below), what

kind of trade was of importance, and why the area changed between being rich and prosperous to being rather poor a few times.

Many clear and detailed maps and drawings were very helpful in this respect; below is one: |

| | |

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

|

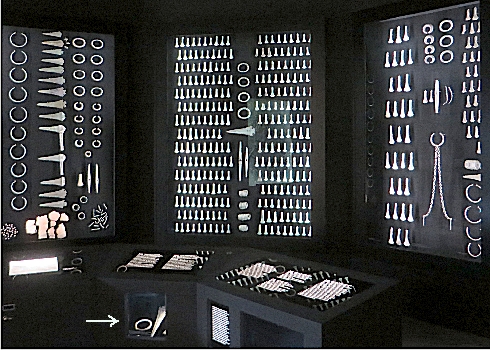

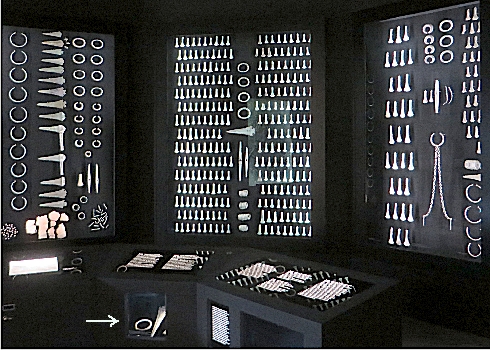

Let's turn to the unbelievably rich collection of

bronze objects in the newly redone room. Here is the centerpiece, showing just parts of what is there: |

| | |

| | |

|

Some of the many bronze objects in a dark room

From around 2.000 - 1.800 BC; when

the region was rich

Large size |

| Source: Photographed in the Museum in April. 2018 |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Note the objects marked with a white arrow. They are almost at floor level and

appear to be made from gold. No description is visible. If you want to find out what it is, you must either lie down on

your belly our point your camera and hope that you will be able to look at a clear picture later.

Here is the best I

got: |

| | |

|

|

|

| | Floor decorations? |

| Source: Photographed in the Museum in April. 2018 |

|

| | |

|

| |

|

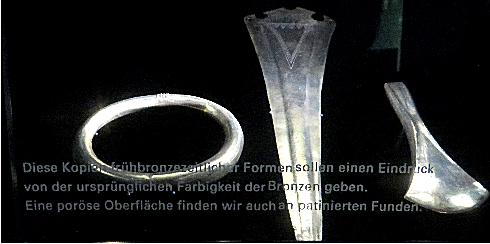

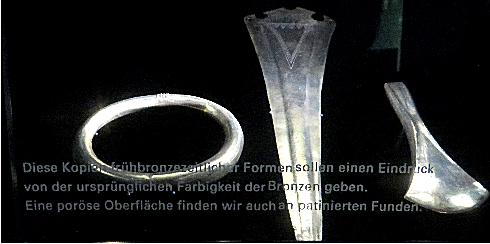

Aha! After heavy contrast enhancement it became possible to read the inscription

on the glass. It tells you that these pieces are modern bronze casts. They are supposed to give you an impression of what

bronze things looked like when they were new and shiny. How anyone with an IQ above that of an avocado can come up with

such a design is a mystery to me. |

|

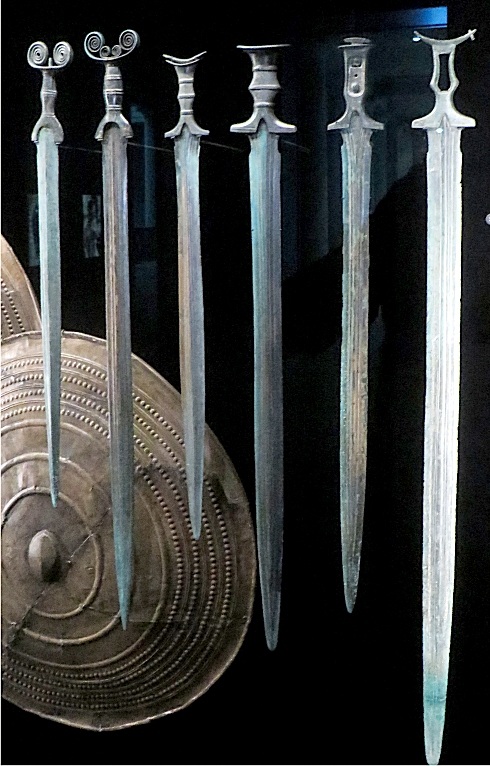

Of course you will see magnificent bronze swords

and other objects (including mysterious ones), too. Here is an example |

| | |

|

|

|

|

Shield and swords from typically 8th - 9th century BC

Large size showing more |

| Source: Photographed in the Museum in April. 2018 |

|

| | |

|

© H. Föll (Iron, Steel and Swords script)